While the trade of slaves was not unknown in India, the scale of slavery in India was extremely small in pre-Islamic times.

By Shanmukh-Saswati Sarkar-Dikgaj-Aparna-Kirtivardhan

One of the worst (if not the absolute worst) atrocities perpetrated by the Islamic regimes in India was the perpetuation of slavery. While the trade of slaves was not unknown in India, the scale of slavery in India was extremely small in pre-Islamic times. There are no descriptions of large scale slavery of either enemy combatants, or slave markets in India. Nor is there any description of slavery of civilians in India. Indeed, Megasthenes remarks that there was no slavery in India, whereas Arthashaastra places a large number of injunctions against slavery. There is no mention of large scale slavery in Kalhana’s Rajatarangini – the only mention of slavery comes from a few high class courtesans being traded. It may be safely asserted that in the ancient times slavery in India was extremely small compared to the slavery that existed in the west, or even in China.

We show that slavery became endemic in India during the Muslim rule, focusing on the Mughal emperors, starting from Akbar, and post-Mughal Muslim rulers. The wealthy and influential Indic mercantile groups enabled the invading Muslim rulers in various different ways, e.g., by funding their campaigns against native kingdoms via loans and contributions, by funding their nobility and managing the finances of the state, by gathering intelligence for them and undermining public morale against them and negotiating on their behalf with other foreign powers. Such acts of collusion render the involved Indic merchants as accomplices to the many atrocities perpetrated by the Muslim rulers on Indic commons, including slavery. But, more, we show that the Indic merchants, not merely enabled the Islamic state as above, but also directly facilitated the slave trade of Indic victims by either directly participating in it, or funding it. While the bulk of the guilt for the atrocities lies on the perpetrating rulers, it must be emphasized that they could not have perpetrated them effectively without the collusion of the big business classes. Thus, the big business classes served as instruments of the oppressive Islamic imperialism. We naturally observe that they were largely exempted from slavery.

We first describe how the Islamic regimes in India acquired slaves from among the Indians. We subsequently show that a strong element of religious persecution was in built into the Islamic slave trade. We next elucidate that the trans-national trade constituted an important vehicle of slave trade. We subsequently establish the complicity of the Indic mercantile in export of Indic slaves from India to Central Asia and Turkey. This establishes that Indic merchants had no sense of nationhood that existed in India from ancient times. We finally show that Indic merchants bankrolled slave economies of Islamic states outside India, and had close political connection with the notorious Islamic rulers of West Asia.

Slavery under Islamic regimes

Mostly the under-privileged, the defeated soldiers of the resistance armies, their women and children (including those of the princes who resisted), that were enslaved. Merchants or their family members were not enslaved on a systematic basis. The peasants constituted the bulk of the enslavements. We discuss the modalities next. Their poverty prevented them from fulfilling the exploitative tax obligations laid on them. The unfortunate peasants who could not pay their taxes were enslaved along with their family, women and children included. It has been documented that villages, which owing to some shortage of produce, were unable to pay the full amount of the revenue, were made captives by their masters and governors, and their wives and children used to be sold on the pretext of a charge of rebellion. Manrique has documented, “they [the peasants] are carried off, attached to heavy oil chains, to various markets and fairs [to be sold], with their poor, unhappy wives behind them carrying their small children in their arms, all crying and lamenting their evil plight.’’ Sometimes the hapless peasants had to fulfill their tax obligations by surrendering their children as slaves.

Frequently the peasants were compelled to sell their women, children and cattle in order to meet the revenue demand. As Jahangir has noted in Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri: “In Hindustan especially in the province of Sylhet which is a dependency of Bengal it was custom for the people of those parts to make eunuchs of some of their sons and give them to the governor in place of revenue (Mal Wajibi) .This custom by degrees in other provinces and every year some children are thus ruined and cut from procreation’’. Manrique, who traveled in India during the reign of Shah Jahan, has recorded instances in Bengal where on failure to pay rent a Hindu had his wife and children sold by auction.

The distress sales by the peasants of their family members substantially exacerbated during famines. In fact, each scarcity was marked by substantial glut in the slave market.. In describing the Deccan famine of 1698-1705, when fathers sold their children, Jadunath Sarkar has quoted Manucci, as, “Aurangzib withdrew to Ahmadnagar, leaving behind him the fields of these provinces devoid of trees and bare of crops, their places being taken by the bones of men and beasts. Instead of verdure all is black and barren. The country is so desolated that neither fire nor light can be found in the course of three or four days’ journey. There have died in his armies over a hundred thousand souls yearly, and of animals, pack-oxen, camels, elephants, etc., over three hundred thousand. In the Deccan provinces from 1702 to 1704 plague (and famine) prevailed. In these two years there expired over two millions of souls.”, and “Nowhere south of the Narmada could grain be found cheaper than six seers a rupee’’, while in certain periods it sold in the imperial camp for two seers or even less … Out of the capital cities of the eight chief subahs of the empire, population has decreased in the three Deccan towns of Bijapur, Haidarabad and Burhanpur, while the villages round them have been totally ruined.’’.

During the 1560s famines in Gujarat, parents used to sell the children for trifles. Peter Mundy has recorded the predicament of the famished of Gujarat during November 1630: “ In this place Men and women were driven to that extremity for want of food that they have sold their children for 12s,6d and a pence apiece.” “And to give them away to any that would take them with many thanks so that they might preserve them alive, although they were sure never to see them again”. Dutch merchant Van Twist records about this famine: ‘Men deserted their wives and children , women sold themselves as slaves ; mothers sold their children; children deserted by their parents, sold themselves .Some families took poison and so died together ; others threw themselves into the rivers …some ate carrion flesh. Others cut up the corpses of men and drew out the entrails to fill their own bellies ; yea men lying on the streets , not yet dead , were cut up by others , and men fed on living men , so that even in the streets , and still more on road journeys , men ran great danger of being murdered and eaten’. We learn more about slavery caused by this famine as: “Life was offered for a loaf but none would buy, rank was to be sold for a cake but none cared for it; the ever bounteous hand was now stretched out to beg for food; and the feet which had always trodden the way of contentment walked about only in search for sustenance. For a long time dogs flesh was sold for Goats flesh, and the pounded bones of the dead were mixed with flour and sold.’’ In 1663-64 a severe famine visited Dhaka. As a result, many people sold themselves to the rich under deeds of sale sealed by the Qazi. In 1671, Bihar experienced a major famine, which stretched into the North West corner of Bengal. A contemporary account, at Patna, left by John Marshall, states, “Great number of Slaves to be brought for 4 an. and 8 an. per piece, and good ones for 1 r. per piece; but they are exceeding leane when bought, and if they eat but very little more than ordinary of rice, or eat any flesh, butter or any strong meat their faces and hands and codds swell immediately exceedingly.’’ Manucci also points out in, “He (Aurangzeb) commanded, therefore, that he (Persian Ambassador) should be intercepted on the frontier, and deprived of all the Indian slaves he was taking away. It is certain that the number of these slaves was most unreasonable; he had purchased them extremely cheap on account of the famine, and it is also said that his servants had stolen a great many children.”

Peasants were also frequently enslaved on pretexts that had nothing to do with the payment of their taxes. Whenever any robbery occurred within the jurisdiction of a jagirdar, they used that pretext to sack any village they suspected. The men were killed in such cases and the women and children were carried away and sold for slaves. In Gujarat, in 1646, Shaista Khan depopulated whole villages of “miserably pore people, under pretense of their harboring thieves and rogues.’’. Villages around the Lakhi jungle had once been guilty of violence. Subsequently, Faujdars used to regularly carry away Dogar peasants from there. Talish describes a despicable practice in Bengal: “When any man, ryot or newcomer, died without leaving any son, all his property including his wife and daughter was taken possession of by the department of the crownlands, or the jagirdar or zamindar who had such power and this custom was called ankura [hooking] ‘’.

Sultan Ala al-Din Khalji owned some 50,000 slaves and later that century Sultan Firuz Tughluq is reported to have owned 180000 slaves

Peasants often rebelled by refusing to pay land revenue. Villages and areas which went into rebellion or refused to pay taxes, were known as `mawas’ and `zor talab’. The revenue paying villages were called `raiyatti’. Manucci has written, that in the rebel villages “everyone is killed that is met with and their wives, sons and daughters and cattle are carried off.’’ Not only the combatants but other inhabitants of the rebel villages were persecuted perhaps as badly. The Faujdars often committed excesses on the rebellious peasants, as Manucci points out: “The moguls call this [rebellious population Zolom Parest (Zulam Parast) that is tyranny adorers , sometimes these faujdars commit excessive acts of oppression which cause rebellion and bring on battle. If the villagers are defeated, everyone is killed, that is met with, and their wives, sons, daughters, and cattle are carried off. The best looking of these girls are presented to the king under the designation of rebels. Others they keep for themselves, and the rest are sold.’’. Most of these unfortunate women would serve as sex slaves to the Muslim royalty and the nobility. The women and children of the households of the Hindu princes who rebelled suffered the same predicament. For example, KS Lal points out that, “the enslavement of women and children too was a common phenomenon … and was revived under Shahjahan; it had not probably been abolished completely earlier. An interesting piece of information supplied by Manucci should suffice here. He gives a long list of women dancers, singers and slave-girls like Hira Bai, Sundar Bai, Nain-jot Bai, Chanchal Bai, Apsara Bai, Khushhal Bai, Kesar Bai, Gulal, Champa, Chameli, Saloni, Madhumati, Koil, Menhdi, Moti, Kishmish, Pista etc., etc., and adds. All the above names are Hindu, and ordinarily these are Hindus by race, who had been carried off in infancy from various villages or the houses of different rebel Hindu princes. In spite of their Hindu names, they are, however, Mohamedan. It appears that the number of such converts was so large that even their Hindu names could not be changed to Islamic.’’ In the same Mughal regime, Bengal Nawab, Sarfaraz Khan, had 1500 pretty female dependents and slaves. Holwell asserts that a principal nobleman in the court of Sarfaraz Khan, Haji Ahmad, [brother of the later Bengali Nawab, Alivardi Khan] “ransacked the provinces to obtain for his master [Sarfaraz Khan], regardless of cost, the most beautiful women that could be procured, and never appeared at the nawab’s evening levee without something of this kind in his hand’’. Bernier also points out that “Of the vast tracts of country constituting the empire of Hindoustan, many are little more than sand, or barren mountains, badly cultivated, and thinly peopled; and even a considerable portion of the good land remains untilled from want of laborers; many of whom perish in consequence of the bad treatment they experience from the Governors. These poor people, when incapable of discharging the demands of their rapacious lords, are not only often deprived of the means of subsistence, but are bereft of their children, who are carried away as slaves. Thus it happens that many of the peasantry, driven to despair by so execrable a tyranny, abandon the country, and seek a more tolerable mode of existence, either in the towns, or camps; as bearers of burdens, carriers of water, or servants to horsemen. Sometimes they fly to the territories of a Raja, because there they find less oppression, and are allowed a greater degree of comfort.”

The harvest of slaves was regular as the peasants frequently rebelled during Mughal rule. Jat peasants rebelled throughout, from the reign of Akbar to Aurangzeb. In 1623, many of them [Jats] were killed, their women and children were taken captive and the victorious troops acquired a great booty. In 1580, Ralph Fitch, the first English visitor to Bengal, found the country to be infested by rebels. The rebellions seem to have continued from the time of Akbar to the time of Aurangzeb. When the kingdom of Koch Behar was annexed in 1661, the local officials introduced their methods of their revenue assessment and collection according to the regulations followed in the Imperial territory. “This caused general revulsion against the conquerors among the peasants, who were treated with much greater leniency by the deposed Raja, Bhim Narayan. They, therefore, rose and expelled the local troops and officials.’’ Hindu mendicant Satnamis led a rebellion of goldsmiths, carpenters, sweepers, tanners and other artisans during the reign of Aurangzeb. Banda Bahadur put together “an army of innumerable men, like ants and locusts, belonging to the low castes of the Hindus and ready to die’’ at his orders, as described by Muslim sources. Other Muslim sources mention that “large numbers of scavengers and tanners and a class of Banjara [ox-transporters] and other lowly persons and cheats became his disciples and gathered (under him)’’. The expressions used for the rebellious peasants indicates the level of contempt for them among contemporary Muslim elites. Innumerable other peasant revolts occurred throughout Northern India during the Mughal regime.

The harvest of slaves was regular as the peasants frequently rebelled during Mughal rule. Jat peasants rebelled throughout, from the reign of Akbar to Aurangzeb. In 1623, many of them [Jats] were killed, their women and children were taken captive and the victorious troops acquired a great booty. In 1580, Ralph Fitch, the first English visitor to Bengal, found the country to be infested by rebels. The rebellions seem to have continued from the time of Akbar to the time of Aurangzeb. When the kingdom of Koch Behar was annexed in 1661, the local officials introduced their methods of their revenue assessment and collection according to the regulations followed in the Imperial territory. “This caused general revulsion against the conquerors among the peasants, who were treated with much greater leniency by the deposed Raja, Bhim Narayan. They, therefore, rose and expelled the local troops and officials.’’ Hindu mendicant Satnamis led a rebellion of goldsmiths, carpenters, sweepers, tanners and other artisans during the reign of Aurangzeb. Banda Bahadur put together “an army of innumerable men, like ants and locusts, belonging to the low castes of the Hindus and ready to die’’ at his orders, as described by Muslim sources. Other Muslim sources mention that “large numbers of scavengers and tanners and a class of Banjara [ox-transporters] and other lowly persons and cheats became his disciples and gathered (under him)’’. The expressions used for the rebellious peasants indicates the level of contempt for them among contemporary Muslim elites. Innumerable other peasant revolts occurred throughout Northern India during the Mughal regime.

During the Mughal war against Pratapaditya in early 17th century, soldiers captured 4,000 women and kept them naked

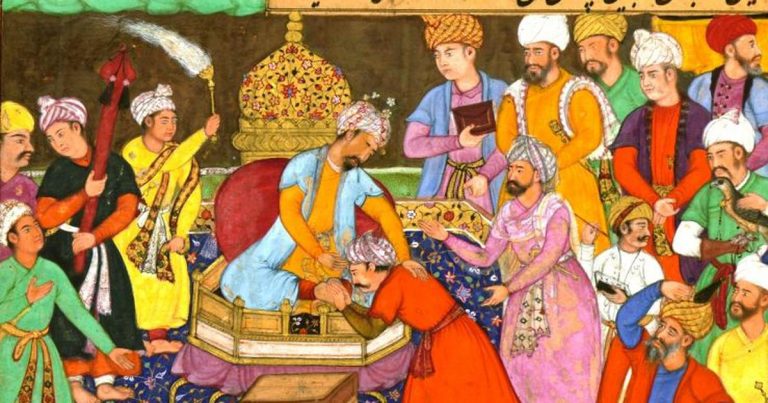

The harvest of slaves multiplied for the Muslim rulers each time they subdued a Hindu kingdom. Scott Levy has documented about the Delhi Sultans, “ as a part of their expansion into new territories, Turko-Afghan armies of the Delhi Sultans commonly abducted large numbers of Hindus. Thus, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, Sultan Ala al-Din Khalji owned some 50,000 slaves and later that century Sultan Firuz Tughluq is reported to have owned 180000 slaves, 12000 of whom were skilled artisans’’. Quoting Afif, RC Majumdar points out the magnitude of the slave taking by the Delhi Sultanate under Firuz Tughluq, stating, “The Sultan commanded his great fief-holders and officers to capture slaves whenever they were at war, and to pick out and send the best for the service of the court. The chiefs and officers naturally exerted themselves in procuring more and more slaves and a great number of them were thus collected. When they were found to be in excess, the Sultan sent them to important cities. In all cases, provision was made for their support in a liberal manner. Arrangement was made for educating the slaves and training them in various arts and crafts. In some places they were provided for in the army. It has been estimated that in the city and in the various fiefs, there were 180,000 slaves for whose maintenance and comfort the Sultan took special care. About 12,000 slaves became artisans of various kinds, and 40,000 worked as military guards to Sultan. The Sultan created a separate department with a number of officers for administering the affairs of these slaves. Gradually the slaves increased to such a degree that they were employed in all sorts of domestic duties, so much so that there was no occupation in which the slaves of Firiiz Shah were not employed.’’. Further, we have evidence of the slave taking of the rebels in Katehr (Rohilkhand), where Shankhdher and RC Majumdar both point out that 23,000 slaves were taken by Firuz Tughluq as vengeance for the revolt of Kharku. We have quoted Bernier before on the enslavement of women of the houses of the rebel Hindu princes. In addition, RC Majumdar has written about the Muslim period in Bengal, “After the conquest of a Hindu kingdom, the Muslims would convert many of the captives into Islam and keep them as slaves, engaged in household duties, the young females among them being taken in as mistresses or reduced to the position of harlots.’’ Scott Levi has added about the Mughal period, “although Emperor Akbar attempted to prohibit the practice of enslaving conquered Hindus, his efforts were only temporarily successful. According to the early 17th century account of Pelseart, Abd Allah Khan Firuz Jang, an Uzbek noble at the Mughal court during the 1620 s and 1630s, was appointed to the position of governor of the regions of Kalpi and Kher and, in the process of subjugating the local rebels, got beheaded the leaders and enslaved their women, daughters and children, who were more than 2 lacks [200000] in number.’’ The Mughal war against Pratapaditya in early 17th century has been described in a contemporary book, Baharistan-i-Ghibi, by Mirza Nathan, the Mughal general leading the war. He has written that his soldiers captured 4,000 women and kept them naked. When, on being informed, he ordered their release, not one of them had any cover on her body. They were somehow covered with trousers, bed-sheets, and any other available clothes and then sent home.

During the wars the Mughuls were capturing the children and forcing them to become dancing girls or slaves.

It is important to note that slave taking during wars had a definite deleterious effect on the Hindu resistance. One eminent example is that of Mewar. It was Prince Khurram’s [Khurram went on to become Shah Jahan] inhuman practice of making prisoners of the women and children that finally took its toll on the Mewaris. RC Majumdar has written, “From the Rajasthan chronicles it is learnt that the condition of the Mewar army was desperate. All provisions and sources of supply were exhausted, and there was even a shortage of weapons. For food they mostly had to depend on fruits. But what hurt them most was, as Jahangir relates, Khurram’s inhuman practice of making prisoners of the women and children. Shyamaldas relates that one day the nobles represented to the crown-prince, Karna that they had been fighting for forty-seven years, under hard conditions. Now they were without food, dress or even weapons, and the Mughuls were capturing their children and forcing them to become dancing girls or slaves. They were prepared to die; each family had lost at least four members in the war; still they would fight, but it seemed to them that even their death could not prevent their family honor from being stained; it was therefore preferable to come to some arrangement with the Mughuls, on the basis of Karna’s personal submission to the Mughul Emperor.’’ Thus, finally, Maharana Amar Singh acquiesced in the submission of Mewar to Jahangir, allowing his crown prince Karna to submit to Jahangir. However, Maharana Amar Singh was a broken man and retired to his inner apartments, leaving the kingdom in the hands of his son, and dying eight years later. Another example is that of Mirza Raja Jai Singh, who was sent to the Deccan to avenge Shivaji’s raid and plunder of Surat, which caused `immense mortification to Aurangzeb and his court’. Jai Singh arrived in the Deccan and organized a flying column to flatten the Maratha villages and it was the destruction and slavery in the Maratha countryside that was one of the reasons that forced Shivaji to come to terms with the invaders and submit to the Mughals, at least temporarily. It is pertinent to note that both these expeditions had significant participation by other Hindus. The state of Amber was an important contributor to the war against both, with Jaipur being a base for the invasion of Mewar and Mirza Raja Jai Singh of Amber leading the invasion of the Deccan to subdue Shivaji. Similarly, Man Singh of Amber had participated in at least one of invasions on Mewar. (Continues)

_________________

Courtesy: Myind.net