Sir Charles Napier found in the Aga Khan “a good and brave soldier” and entertained a very high opinion of his political sagacity and chivalry as a leader and soldier.

From Ismaili Net

The services rendered by the Aga Khan in Sindh were politically speaking of no less importance than those he rendered at Kandhar, since Sindh was regarded as the gateway to India and through it, the foreign conquerors have from time immemorial poured into India. Sir William Lee-Warner has pointed out in “The Protected Princes of India” that, “If Sindh had not fallen to the Company, it must have been either annexed by Afghanistan or absorbed with Lahore by Ranjit Singh.” Soon after the conquest, the Aga Khan again tried to pacify the Mirs and won most of them over to the British side. Sir Charles Napier found in the Aga Khan “a good and brave soldier” and entertained a very high opinion of his political sagacity and chivalry as a leader and soldier.

Soon after the conquest, the Aga Khan again tried to pacify the Mirs and won most of them over to the British side

In those days, the route between Karachi and Hyderabad was controlled mostly by the Jokia tribe and it was difficult for Col. Boileau, who was commanding a British regiment to communicate with Charles Napier. The Jokias and other tribes had created conditions of complete lawlessness and disorder on the outskirts of Karachi. Communication with the outside world was absolutely paralyzed. A detachment of troops which was going from Karachi to Hyderabad to join Charles Napier was attacked at Gujjo by Jokias in 1843 under the leadership of Chakar Khan. Naomul Hotchand (1804-1878) writes in “Memoirs of Seth Naomul Hotchand” (London, 1915, p. 129) that, “The depredations of the Kalmatis, Numries, and of the Jokhias on the outskirts and in the vicinity of Karachi struck terror in the hearts of the people, and all intercourse and communication with the outside world was cut off.” H.T. Lambrick also writes in his “Sir Charles Napier and Sind” (London, 1952, p. 157) that, “Bands of Baluchis had plundered most of the wood and coal stations on the Indus, interrupted the mail route to Bombay via Cutch, and also the direct road to Karachi, whence supplies and artillery had been ordered up. With a view to reopening communications with Karachi, Sir Charles sent the Agha Khan to take post at Jherruk with his followers, some 130 horsemen.”

In sum, plunders and violence and consequent fear of unsafety to person or property, did not cease. Sir Charles Napier, therefore, posted the Aga Khan at Jerruk at the end of February, 1843 to secure communications as well as restore peace between Karachi and Hyderabad. Napier also wrote to Ellenborough on February 25, 1843 that, “As it is a matter of considerable importance to prevent marauding, and as he (the Aga Khan) is not only a brave man, as head of the religious sect, has much influence and numerous followers, I have desired him to do so till I have your Lordship’s decision.” Napier also informed Col. Boileau, the officer commanding at Karachi, about the posting of the Aga Khan and his responsibility for guarding the post between Hyderabad and Karachi in Jerruk.

Sir Charles Napier wrote in his diary on February 29, 1843 that, “I have sent the Persian Prince Agha Khan to Jherruk, on the right bank of the Indus. His influence is great and he will with his own followers secure our communication with Karachi. He is the lineal chief of Ismailians, who still exist as a sect and are spread all over the interior of Asia.”

The Jirakia tribe of lower Sindh is reported to have settled in this locality, making it known as Jerruk

Jiraq, Jhirak, Jherruck or Jerruk (25 degree 3′ north latitude and 68 degree 18′ east longitude), a town in the Kotri Taluka, is situated close to the Indus, at an elevation above it of 150 feet, on the range of limestone hills that runs along its right bank south of Kotri. The Jirakia tribe of lower Sindh is reported to have settled in this locality, making it known as Jerruk. The old town of Manchaturi or Manjabari as reported by the Arab historians like Istakhri of the 10th century and Idrisi of the 12th century, appears to have been situated in the neighborhood of Jerruk.

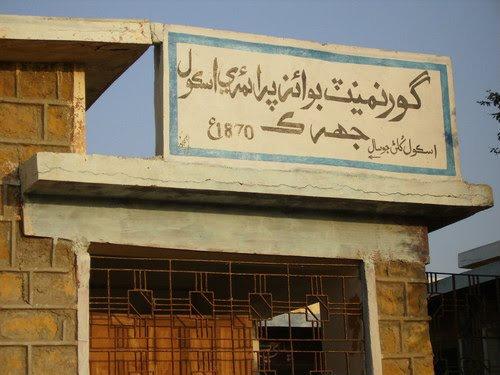

The early history of Jerruk has been but little, if at all, investigated and is involved in the greatest obscurity. There is a ruined site in the neighborhood of Jerruk, which is called by the local people as Kafir Kot and is supposed to have been built by Raja Manjira. This site also contains remains of Buddhist and Hindu structures with a very curious inscription in old Indian character. It suggests that the existence of Jerruk goes back to the time of Raja Manjira. From its situation, commanding the river as well as the roads from Karachi and Thatta, Sir Charles Napier, who made it a Military Depot, considered it a position of some importance. Afterwards it was an outpost garrisoned by a company of sepoys. It was also the headquarters of the Deputy Collector. For many years it had been a Missionary Station. It had a Municipality, but that was abolished in 1878. On a hill to the north of the Kotri road and close to the town is the grave of an Assistant Surgeon Robert Hussey, who died here in 1850, and in another spot lie the remains of the Reverend C. Huntingdon, Chaplain of Hyderabad, who died here on his way to Karachi on May 27, 1856. It was here that W. Cole once Collector of Customs in Karachi, found some Buddhist bricks which were afterwards deposited in the Karachi Museum. It is also learnt that the first Sindhi Primary School in Jerruk was established in 1873. In the Indian Museum, Calcutta, there is a flint scraper reported to have been found by Dr. Fedden of the Geological Survey, on the surface at Jerruk in 1876.

The early history of Jerruk has been but little, if at all, investigated and is involved in the greatest obscurity. There is a ruined site in the neighborhood of Jerruk, which is called by the local people as Kafir Kot and is supposed to have been built by Raja Manjira. This site also contains remains of Buddhist and Hindu structures with a very curious inscription in old Indian character. It suggests that the existence of Jerruk goes back to the time of Raja Manjira. From its situation, commanding the river as well as the roads from Karachi and Thatta, Sir Charles Napier, who made it a Military Depot, considered it a position of some importance. Afterwards it was an outpost garrisoned by a company of sepoys. It was also the headquarters of the Deputy Collector. For many years it had been a Missionary Station. It had a Municipality, but that was abolished in 1878. On a hill to the north of the Kotri road and close to the town is the grave of an Assistant Surgeon Robert Hussey, who died here in 1850, and in another spot lie the remains of the Reverend C. Huntingdon, Chaplain of Hyderabad, who died here on his way to Karachi on May 27, 1856. It was here that W. Cole once Collector of Customs in Karachi, found some Buddhist bricks which were afterwards deposited in the Karachi Museum. It is also learnt that the first Sindhi Primary School in Jerruk was established in 1873. In the Indian Museum, Calcutta, there is a flint scraper reported to have been found by Dr. Fedden of the Geological Survey, on the surface at Jerruk in 1876.

We have good authority for interring that the Ismailis had settled in Jerruk before the period of Sayed Fateh Ali Shamsi (1733-1798), who hailed from the Kadiwala family

Jerruk occupied an irregular space of seven furlongs in circumference, about 150 feet above the river level. It is spread on 5087 acres. It is on an abrupt rocky tableland, having two hills close to the town, which covered the approaches by land and by water. The historic town of Jerruk is located between Hyderabad and Thatta in Sind, where wheat, rice, sugar-cane, cotton, vegetables and some fruits are grown in abundance. Supplies were abundant, much cheaper than at Karachi. There were in the market 200 shops and the street, which contained them, was covered over with matting from side to side. Jerruk is at an altitude of about 500 feet and a very fine picturesque place. It has a healthy climate and was used as a healing station in Sind for many years. It will be interesting to know that a big hanging lamp was installed on the main gate of the fort of Hyderabad, whose light was clearly visible in Jerruk at night. At Jerruk on both sides of the river, we have perhaps the thickest riverine forest in Pakistan. The zoological genera of Jerruk are but little known. It is however a habitat for gazelle, wild boar, wild cat, hare, crocodile, etc. The Aga Khan liked its pleasant climate and the hunting ground. Captain T. Postans had completed his “Personal Observations on Sind” (Karachi, 1973, p. 27) on April, 1843 and wrote that, “Jerruk, situated above Tatta, on the same bank of the river, is a neat town, and its effect from the river is remarkably pleasing, in consequence of the abundance of foliage around it, in the form of shikargahs: it also occupies a commanding site on a ledge of rocky hills overlooking the streams.”

Neighboring tribes of Jokia, Numeri and Kalmati who had joined Sher Muhammad Khan, threatened the Aga Khan and his followers with death, on account of their having joined the British

We have good authority for interring that the Ismailis had settled in Jerruk before the period of Sayed Fateh Ali Shamsi (1733-1798), who hailed from the Kadiwala family. He was a famous vakil and with his indescribable efforts, a large proselytism had been resulted in lower Sind by leaps and bounds. He died in 1798 and his shrine exists near Jerruk. In 1829, Bibi Sarcar Mata Salamat (1744-1832), the mother of Imam Hasan Ali Shah, the Aga Khan I had visited India with Mir Abul Kassim (d. 1880). She made a brief stay in Jerruk before going to Bombay. Jerruk was also famous for the Akhund families of Kutchh. In those days, most of them were learned and transcribed the ginans (religious hymns) by hands. They usually visited the villages in district Thatta and Shah Bandar and sold the copies as a mean of livelihood.

The Aga Khan rode out of Hyderabad and reached Jerruk after a travel of 20 miles on March 1, 1843, where about 1000 Ismailis had thronged from Sindh, Kutchh, Kathiawar, Gujrat and Muscat to behold their Imam. The Ismailis were warmly hosted and repasted daily by Vesso, Vali and Datoo, the sons of Seth Merali of Jerruk.

When Sher Muhammad Khan advanced with his army on Hyderabad, the Aga Khan wrote letter to all the Baluchis, inviting them to become subject of the British government. He also addressed to Sher Muhammad Khan not to risk an action

Soon after his arrival, the Aga Khan and his horsemen whose number had risen to two hundred took up their post near Jerruk and helped to safe guard the post from Karachi and also to make speedy delivery of letters and supplies for the British forces in Hyderabad. The mail between Karachi and Hyderabad was very irregular before the Aga Khan took over the charge. It seems that he spread his soldiers around Jerruk and Thatta to monitor over the situation. While guarding the road between Karachi and Hyderabad, the Aga Khan also recovered the British property which had been plundered from the camp of Thatta by the Baluchis. When Sher Muhammad Khan advanced with his army on Hyderabad, the Aga Khan wrote letter to all the Baluchis, inviting them to become subject of the British government. He also addressed to Sher Muhammad Khan not to risk an action through a letter. The Hindu clerk, Kundahri carrying the letter and two other servants, accompanying him, were killed by Sher Muhammad.

The neighboring bigoted tribes of Jokia, Numeri and Kalmati who had joined Sher Muhammad Khan, threatened the Aga Khan and his followers with death, on account of their having joined the British. The local tradition has it that the first group of the prisoners were taken on February 26, 1843 soon after the battle of Miani on February 17, 1843 and were sent to Calcutta. They were taken away from the fort of Hyderabad to the river and thence by a steamer, Nimrod, stirring from Hyderabad to Karachi and thence to Calcutta. When the steamer passed near Jerruk, it is attested in the tradition that a crowd of the people climbed on the hill to see the steamer carrying the prisoners. It is said that some Ismailis on the hill hailed and saluted the British soldiers, and condemned with hooting the action of the Mirs. This aroused hostility between the supporters of the Mirs and the Ismailis in Jerruk, resulting an attack upon the Ismailis. According to another tradition, the people belonging to the tribes of Numeri and Mallick, who hetched an animosity against the growing influence and affluence of Vesso or Vessar and Vali, the sons of Merali, joined hands with the enemies of the Ismailis, and it was more likely a bone of contention of the incident of Jerruk. (Continues)

__________________

Click here to read Part-I