When Bulleh Shah died in 1757, the local Imams termed him as heathen and refused to lead his funeral prayers. It was not unexpected. He had thus antagonized them a great deal and they, in turn, regarded him as an apostate.

Parvez Mahmood

Pakistan’s indigenous languages have a rich literary heritage, producing some towering poets whose verses depict sentiments and idioms of the common people. At the same time, it is regrettable, and this author has written about this indifference, that folk poetry has been neglected in our schools and colleges. While the Urdu syllabi books at primary and middle level include a number of chapters on Islamic topics, they do not contain even a single passage or verse from Sufi poets of local languages. This is, perhaps, the greatest assault on Pakistani culture, that too inflicted by our own people. Someone needs to make amends before our children forget the names of Rahman Baba, Mast Tawakli, Shah Abdul Latif and Khwaja Farid. That would an irreparable national loss.

This article depicts the life and poetry, as well as socio-political environment, of Bulleh Shah who, because of his continued popularity with every section of society, can rightly be called the poet of the people. There are many published books on Bulleh Shah. This author has three books in his e-library namely Kalam Hazrat Baba Bulleh Shah by Samiullah Barkat, Bulleh Shah Kehnday Nain by Maqbool Anwar Daudi and Bulleh Shah ka Kalam with Urdu translation by Ali Akbar Abbas.

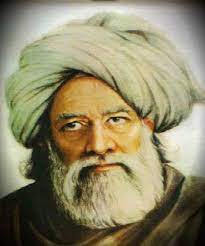

Bulleh Shah was born in 1680 in Uch Sharif; a sacred town where lived and is buried Jalaluddin Surkhposh Bukhari, a renowned saint whose illustrious descendants include, among others, Jahaniyan Jahangasht, Baba Shah Jamal and Mauj Darya Bukhari. Some researchers include Surkhposh as an ancestor of Bulleh Shah too.

Bulleh Shah was named Abdulllah Shah Qadri but is immortalized by his loving soubriquets of Baba Bulleh Shah, Bulla and Bulleha. His father left Uch Sharif and settled in Malakwal for a few years before moving to Pandoke, a village southeast of Kasur. His initial education included Persian and Arabic, and was conducted under his scholar father, but later he adopted Shah Inayat Lahori as his spiritual guide. His choice of teacher became scandalous because Shah Inayat was from Arian caste, meaning a farming family whereas Bulleh Shah was a Syed. However, Bulleh Shah believed in the equality of human beings irrespective of religion, race or creed. He says:

Bullyay! Chal othay challya, jithay sarey annay

Na koi sadi zat pehchanay, na koi sunnuu mannay

(Bulleh Shah! Go to a land where people are blind to lineage and beliefs)

Caste, along with its wicked offspring, untouchability, is the vilest institution produced by humans. It’s a sad reflection that though Islam declared piety as the sole basis of superiority, the Turk and the Persian ruling classes of India adopted the caste distinctions by treating themselves as Ashraf meaning superior, to the local converted Muslims whom they termed as Azlaf meaning the low-born. A Syed or a Mirza sought a superior social status to Jats, Arains or Gujjars. The local converted Muslim adopted suffixes of Quraishi, Farooqui, Siddiqui, Khawaja, etc., to raise their social status. Sanobar Umer notes that ‘Many Muslims from the weaver caste began to identify as “Ansari”, the butchers as “Qureshi”, and the sanitation and water-carrier caste as “Sheikh”.

Caste based division was rife in the days of Bulleh Shah, therefore, it appears exhilarating and refreshing that a poet, that too of a Syed lineage, should base primacy on piety and not on birth, caste, religion or wealth. He wrote:

Maut na dekhey umar noon; Tey ishq na dekhey zat’

(Death is not deterred by age, nor love by caste)

He also makes the extreme distinction:

Kanjari BaniyaaN Meri Izzat Na Ghat Di

Mainu Nach Ke Yaar Manaawan De

(Being a harlot does not lessen my dignity;

Let me dance to charm my Love)

Bulleh Shah’s character and intellect were forged through a troubled period. He died in the year of Battle of Plassey. In between, he lived through Aurangzeb’s disastrous Deccan campaigns, unending palace intrigues in Mughal Delhi, murder of reigning emperors, breaking away of outlying provinces, British incursion along Carnatic Coast, Nader Shah’s murderous sacking of Delhi and the plundering raids of Abdali. It was a distressing time, especially for Punjab.

Simultaneously, the British commenced their relentless plunder of Bengal in 1757, followed by systematic expansion to the heartland of the subcontinent. Displaying utter disdain for the vanquished, the British termed the Indians as uncivilized savages and downplayed their scholarly achievements. However, the Indian poets of the era remind us that their intellectual vitality and literary diction remained intact. Bulleh Shah’s Punjabi/Sindhi contemporaries were Shah Abdul Latif (1690-1752), Waris Shah (1722-98) and Sachal Sarmast (1739-1827), and his Urdu contemporaries were Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810), Mir Dard (1720-85) and Mirza Sauda (1713-1781). This poetic heritage continues to delight the readers. In those trying times, Bulleh Shah endeavored to maintain human dignity.

Simultaneously, the British commenced their relentless plunder of Bengal in 1757, followed by systematic expansion to the heartland of the subcontinent. Displaying utter disdain for the vanquished, the British termed the Indians as uncivilized savages and downplayed their scholarly achievements. However, the Indian poets of the era remind us that their intellectual vitality and literary diction remained intact. Bulleh Shah’s Punjabi/Sindhi contemporaries were Shah Abdul Latif (1690-1752), Waris Shah (1722-98) and Sachal Sarmast (1739-1827), and his Urdu contemporaries were Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810), Mir Dard (1720-85) and Mirza Sauda (1713-1781). This poetic heritage continues to delight the readers. In those trying times, Bulleh Shah endeavored to maintain human dignity.

Masjid dha dey, mandar dha dey, dha dey jo kuch dhendha

Ik banday da dil na dhaween, rab Dillan wich rehda

(Tear down everything that can be destroyed but not the human heart; the abode of the Lord)

Though Bulleh Shah’s poetry maintained its immense appeal through the centuries among the masses in rural areas, its urban revival took place when folk and qawwali singers found that his poetry had powerful appeal and was, thus, a sure route to success. The leading revivalist of Bulleh’s poetry were Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Sain Zahoor, Abida Parveen, Saeen Zahoor, Nooran Sisters, etc. His powerful poetry proved a booster for their career, fame and recognition. Across the border, in Indian Punjab too Bulleh Shah remained popular in the Sikh community where Rabbi Shergill rendered his iconic ‘Bulla ki Jaana main kaun’ in pop style and the trend continued. It is amazing that a 16th/17th century poet is sung in 20th century music.

Bulleh Shah is popular because he insisted on self-discovery and derided religious rituals as no consequence. He says:

Rab rab karde budhe ho gaye, Mulla Pandat saray,

Rab da khooj khurra na Lubha, Sajde kar kar haare,

Rab te tere andar wasda. Wich Qur’aan ishaare,

‘Bulleh Shah’! Rab unho milsi jhehra apne Nafs nu mare

(Priests have prostrated all their lives

but have not found the essence of Lord,

Quran guides that the Truth lives within us

Bulleh Shah; Truth is found by negating self)

Bulleh Shah believed in appeasing the beloved; which in Sufism means the Supreme Deity. He doesn’t let his ego stand in the way:

nach nach key yaar mana lyea; pawain kanjri banna pey jaway

(I will appease the beloved, even if I have to dance like a harlot)

In another verse he says:

Ishque dey maray aiwnway phirday, jeewain jungle wich dhor

(Lovers wander, as beasts ramble through wilderness)

Bulleh Shah’s iconic poem is ‘Bulla ki janan main kaun’, meaning ‘I don’t perceive who I am’. It portrays complete denial of self-awareness, perception of any reality, association with any national identity and attachment with any religious denomination. It is a charter for secularity and equality. The poem depicts the Sufi doctrine Wahdat-ul-Wajoodiat or Unity of Creation. Consider these selective verses of the poem:

Na main momin vich maseetaan

I am not a believer inside the mosque,

Na main moosa na firoun

I am neither Moses, nor the Pharaoh,

Na main aabi na main khaki

Not from water, nor from earth,

Na main aatish na main paun

Neither fire, nor from air,

Na main arabi na lahori

Not an Arab, nor Lahori,

Na hindu na turak peshawri

Nor a Hindu, Turk, or Afghan.

When Bulleh Shah died in 1757, the local Imams termed him as heathen and refused to lead his funeral prayers. It was not unexpected. During his lifetime, he had given them ample reasons to hate him. For their rituals, he said:

Raati jage, kare ibadat

Raati jagan kutte, Tain to uttey

“You supplicate at night, so do the dogs who are better than you”

He exposed their hypocrisy too:

Haram di peeti janday au; namazan vi neeti janday au

Haj vi keeti janday au; tey laho vi peeti janday au

(You sip free liquor and then stand for prayers

You go on pilgrimage but suck blood off the people)

He had thus antagonized them a great deal and they, in turn, regarded him as an apostate. He stood in august company on this vilification. When the historian and jurist al-Tabari died in 923AD, he had to be buried at night in secrecy for fear of Hanbilites who didn’t accept him as a Muslim. Philosopher Ibn-Rusd was exiled to the Jewish quarter of Cordova under the pressure of Malikites, who considered him a renegade. Physician Al-Razi too was declared a non-Muslim due to his rational attitude towards religion. In our own time, officials faced great difficulty in finding a willing Imam to say the funeral prayers of Salman Taseer for standing up to misuse of blasphemy laws. Our saint Abdus-Sattar Edhi faced the wrath of clergy for serving humanity irrespective of religion and once declared that he wouldn’t like to share paradise with the mullahs. Sadly, we too in Pakistan have judged our finest on the touchstone of bigotry. As Bulleh Shah wistfully said:

Dunya razi ho nahi sakdi

banda mukda muk janda aye

(One can’t charm the people,

even if we struggle all our life)

_____________________

Courtesy: The Friday Times Lahore