Author discusses Ashrams, Asthans, Dharamshalas, Marhis, Maths, Mosques, Samadhis, Shrines, Temples and Sikh Darbars.

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Shikarpur

An open museum and its every street is a heritage street.

At its peak, Shikarpur had eight gates, and life inside was vibrant and lively. The city originated in 1617, as a hunting ground of the princely Daudpota family. In 1701, it was taken over by the Kalhoras. In the eighteenth century, Shikarpur was the commercial emporium of Asia, with traders who ventured into Central Asia on one side and had dealings with Africa on the other. The rich merchants of Shikarpur spent money on its beautification, and the city has temples, mosques, shrines, Sikh darbars, dharamshalas, maths, marhis, samadhis, ashrams and asthaans – places of worship of a variety of religious sects – located in its narrow and winding streets. There is also a covered bazaar. Today these are mostly all in shambles, with the woodwork crumbling and their mural paintings in advanced stages of decay. However, the romance of Shikarpur lives on. In many ways it is an open museum, and its every street is a heritage street.

Khatwari Darbar was founded by Bhai Gurdas, disciple of Guru Gobind Singh, and the founder of Sevapanth. Bhai Gurdas, born Kanaiyalal, received blessings from Guru Gobind Singh. It is said that when Guru Gobind Singh was attacked by the troops of Aurangzeb, Kanaiyalal was entrusted the responsibility of serving water to the injured Sikh soldiers.

However, he was observed serving water to the wounded, regardless of whether they were Sikh or Mughal. When Guru Gobind Singh was Sindhi Tapestry informed that a Sindhi Sikh from Shikarpur was serving water to the enemies, he understood that this was a great soul and blessed him, and instructed him to preach Sikh thought and ideology in Shikarpur. Bhai Gurdas began doing so. He sat on a cot while delivering his sermons, so the darbar came to be called Khatwari Darbar.

The darbar, a two-story building in the haveli style, is one of the impressive structures of Shikarpur, its distinctive features being paintings and woodwork. The walls of the darbar are adorned with paintings representing Hindu and Sikh beliefs, with images of the ten Sikh Gurus on one of the walls. Three doorways open to the main hall of the darbar, which contains the Guru Granth Sahib. Two of the doors are carved with images of Sikh Gurus and Hindu deities, and the third has the companions of Baba Guru Nanak, Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana, represented.

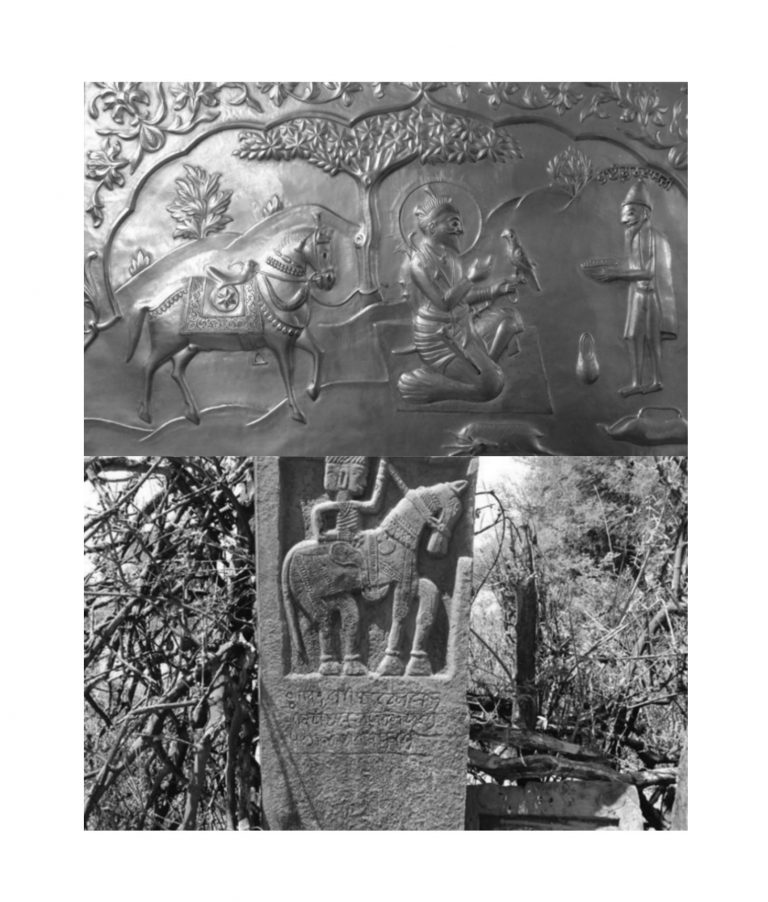

The popular iconography of Bhai Gurdas shows him standing with a bowl of water before Guru Gobind Singh. This theme has been represented in woodwork, painting, and metalwork, and can be seen in various temples around Shikarpur. Most remarkable are reliefs on two metal plates fixed to a wall of a small temple located on the left of the first door. One shows Bhai Gurdas standing before Guru Gobind Singh. The second depicts the darbar of Baba Atal Rai, a son of the sixth Sikh Guru Hargobind Sahib, with four disciples standing before him. Many of Baba Gurdas’s disciples spread his thought and ideology. They came to be known as Sevapanthis, and established darbars and dharamashalas in many towns of Sindh and Balochistan.

Bhai Gurdas himself is believed to have visited Balochistan to spread Khalsa ideology. One of his disciples established an impressive darbar in the heart of Gandava. This darbar too is noted for the wooden frame that decorates its main facade. It depicts Baba Guru Nanak with Bala and Bhai Mardana, Ganpati and Krishna. The names of the caretakers of the darbar are written on the walls in one of the rooms, which include Baba Seetaldas, Baba Dharamdas, Baba Jairamdas, Baba Amardas, Baba Gobinddas, and others.

There were also other Khalsa darbars in Shikarpur which were founded by Diyal Singh, who was also a soldier of Guru Gobind Singh and fought the Mughal troops. He founded the darbar located in Nandi Bazaar, which came to be called Singhan Wari Darbar. Masand Darbar was also founded by a Khalsa saint, Bhai Dhanraj.

Apart from Khalsa darbars, there are many Udasi darbars in Shikarpur which include Samad Ashram Udasin, Chhatwari Darbar and Baba Tulsidas Udasi Darbar. Shikharpur was also home to many ascetics of different persuasions: sanyasis, tyagis, bairagis, sants, naths, gars, bhartis, and others. Dwarka Nath Ji Marhi, Balkram Ji Marhi and the ashram of Shankar Bharti are some of the sacred places associated with Hindu ascetics in Shikarpur.

The shrine of Shankar Bharti is noted for its ornately carved wooden door, paintings and domes that crown the samadhis of Shankar Bharti and his disciples. The main door of Shankar Bharti’s samadhi is carved with the image of Baba Guru Nanak and his two companions Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana.

Many of the ornate wooden carved doors of havelis and darbars have been sold and some can be seen on display at Golra Mor Furniture Market, Islamabad.

Sadh Belo

One of the most sacred spaces of the Hindus

Bukkur and Rohri had many sacred spaces, some of which vanished into the waters of the Indus River when the river flooded or changed course. The island of Sadh Belo withstood its waters. It came into the limelight in the British period, when Baba Bankhandi arrived in Bukkur. He made this island his permanent abode and began preaching his faith. However, Sadh Belo had been home to many religious communities since ancient times. Some halted at the island for a temporary period while others made it their permanent abode. Much before the arrival of Baba Bankhandi, Sadh Belo was one of the sacred spaces of naths who practiced austerities on the island and it is the samadhis of the holy ones from which the name Sadh Belo is derived: the final resting place of sadhus.

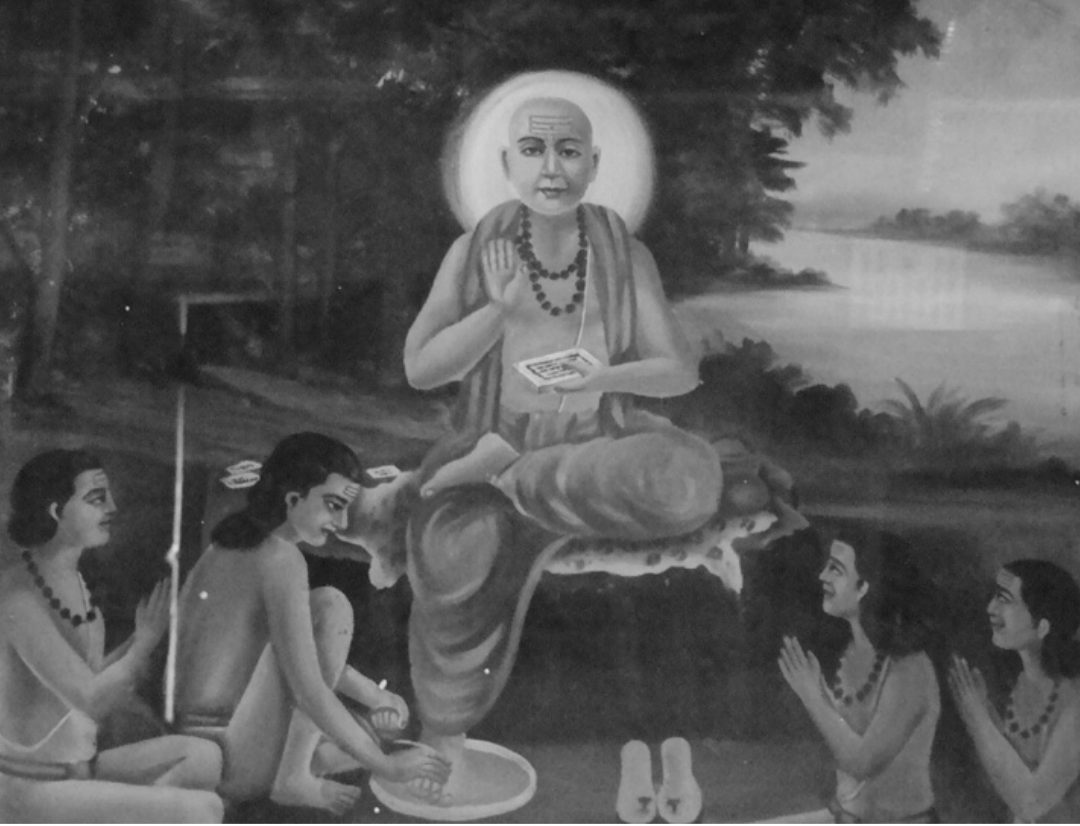

Baba Bankhandi was not a Hindu, but an Udasi. Udasipanth was founded by Baba Srichand, the eldest son of Baba Guru Nanak. The word ‘udasi’ is derived from the Sanskrit ‘udasian’ – detachment from worldly concerns and comforts, and Udasi is an ascetic order within the Sikh religion. The Udasis do not marry, and their spiritual traditions continue througha guru-chela framework. Like naths, the mahant Udasis also establish their dhunis – sacred fire altars, which denote their renunciation.

After Baba Srichand renounced the world, he continued to travel and preach. In Sindh, he established his dhunis in Rohri and Thatta, and these are sacred places for Udasis. Udasi mahants continued to spread the teachings of Baba Srichand in the towns and villages of Sindh, including in Pir Jo Goth, Khairpur, Babarloi and Halani.

Baba Bankhandi was a boy when he left Nepal on his spiritual quest, and his wanderings took him to the dhunis in Rohri and Thatta. In time, he settled at Sadh Belo.

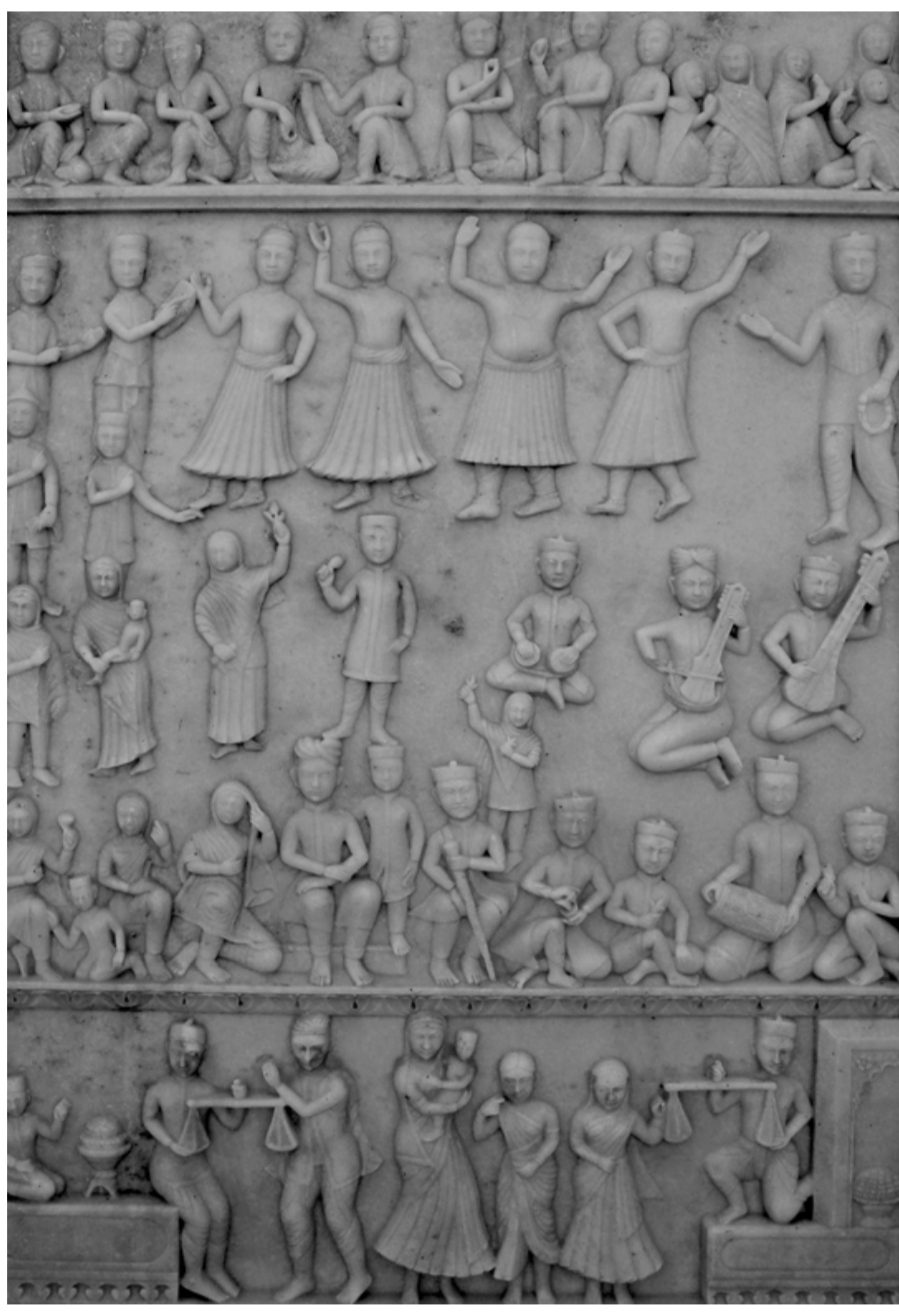

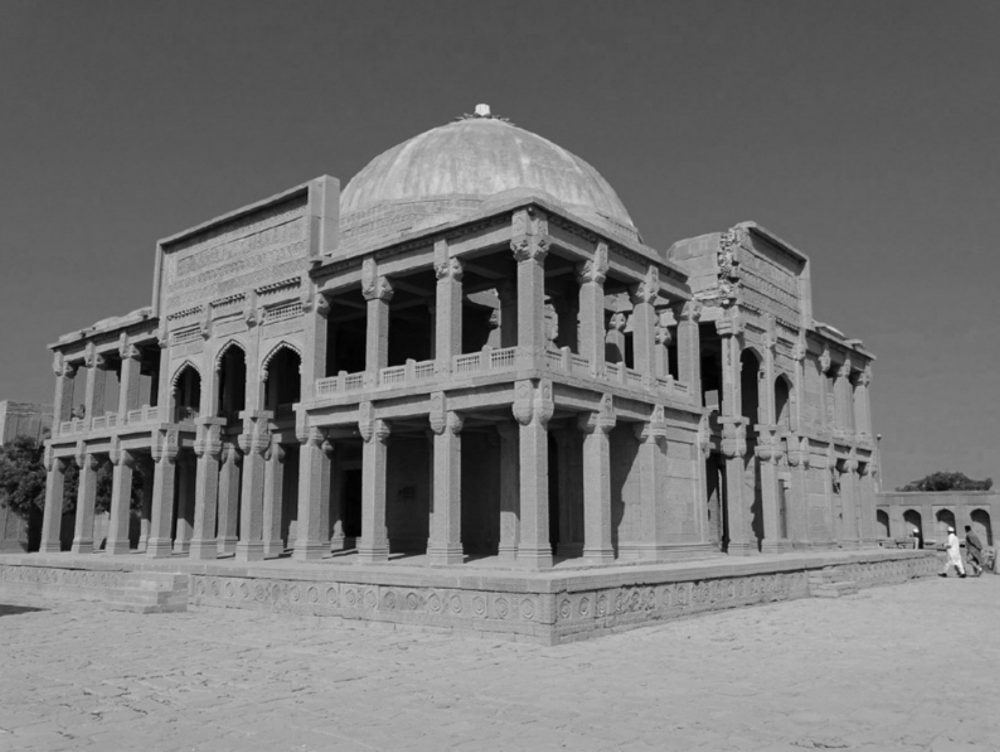

Today Sadh Belo is one of the most sacred spaces of the Hindus of Pakistan, and of Sindh in particular. The darbar of Baba Bankhandi is one of the most impressive marble structures in Sindh. The building depicts both floral and figural representations of Hindu deities and Udasi saints. The northern wall is rich with marble panels depicting the ten incarnations of Vishnu, as well as animal and bird panels. One ‘naraka’ – hell – panel depicts seven hellish realms which show sinners being punished according to their sins. Nearby, the ‘svarga’ – heaven – panel is seen, where people are dancing and playing instruments. One panel shows Vishnu as a liberator, protecting the elephant Gajendra from the clutches of Makara the crocodile. The motif of ‘Gajendra Moksha’ – the liberation of Gajendra – became a popular theme in the Hindu and Sikh shrines of Sindh, represented in marble relief, mural paintings, and wood carvings. The best examples of Gajendra Moksha scenes were carved on the wooden doors of Shikarpur and other towns in upper Sindh. Besides the darbar, Sadh Belo also has a library and a dispensary as well as temples of Hanuman, Ganesh, Durga and Jhulelal. These structures are believed to have been funded by rich merchants of Sukkur such as Mukhi Devan. Entering the mandar of Jhulelal one sees two images – Jhulelal standing on a fish, his vehicle, and Rama Pir, sitting on a horse. It is interesting – and I must say peculiar to Sindhi syncretic traditions – that a Dalit deity is placed together with the deity of upper-caste (Vaishya) Hindus.

Makli

One of the largest necropolises of the Islamic world

Makli is one of the largest necropolises of the Islamic world – spread over 12 square kilometers, and containing the tombs and graves of kings, princes, queens, poets, religious scholars and others, a vast and aweinspiring acreage of beautiful monuments erected to honor the dead.

The Samma (1351-1524) were the first rulers to erect these structures on Makli Hill, followed by the Arghuns (1524-1555), the Tarkhans (1555-1592) and the Kalhoras (1737-1783).

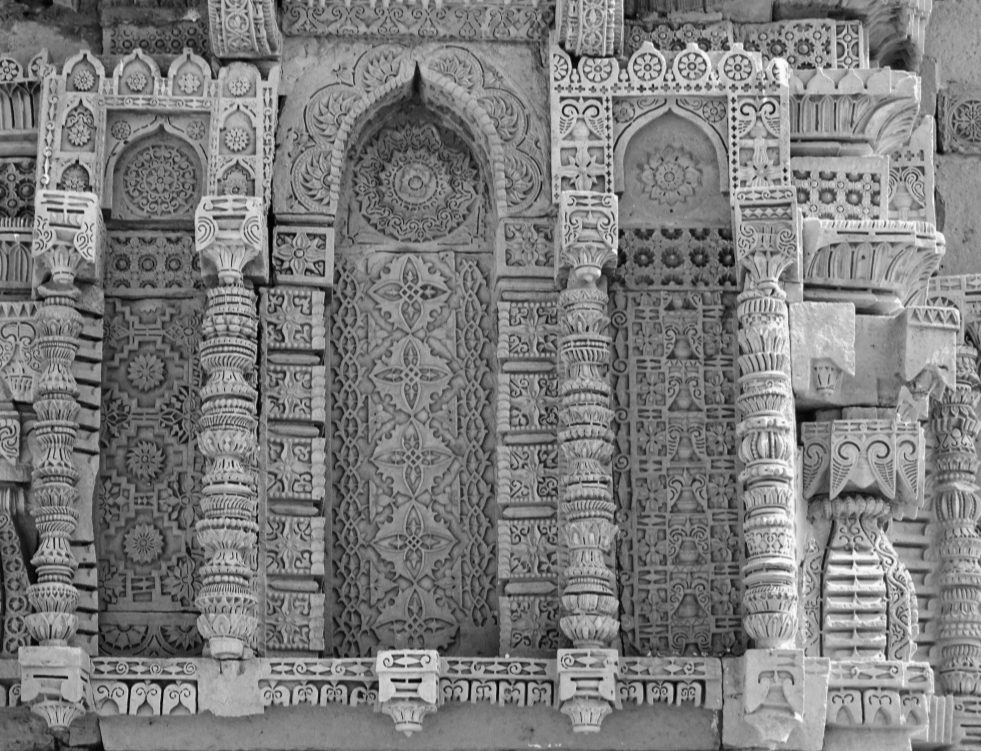

The most splendid tomb encases Jam Nizamuddin, alias Jam Nindo, the longest-serving Samma king of Sindh. The intricate carvings on the façade and mihrab of the tomb make it one of the finest architectural marvels in tomb architecture, which showcases the outstanding skill of the Sindhi master craftsmen of the era. Besides stone carvings, the Tarkhans used ceramics and glazed tile decorations profusely in their monuments, and some are etched with beautiful calligraphy.

As the tombs proliferated on the hillside, they attracted many mystics who settled here, and hermitages – khanqahs – developed around them. Some believe that Makli is named after a female saint whose grave is located west of the Jami mosque of the Samma period, but others pontificate that it is the abundance of graves of saints that provoked the name ‘Makkah li’ meaning ‘Makkah for me’.

Hero stones

These memorial stones are erected for men who died in battle, or for women.

It was in 1999, after I read Romila Thapar’s Death and the Hero, that I began to develop an interest in memorial stones. I began searching for similar monuments in Sindh, but they were completely unknown then. Over time, I have documented more than two thousand such stones all across the Tharparkar region of Sindh, and I believe that there are many more to unearth.

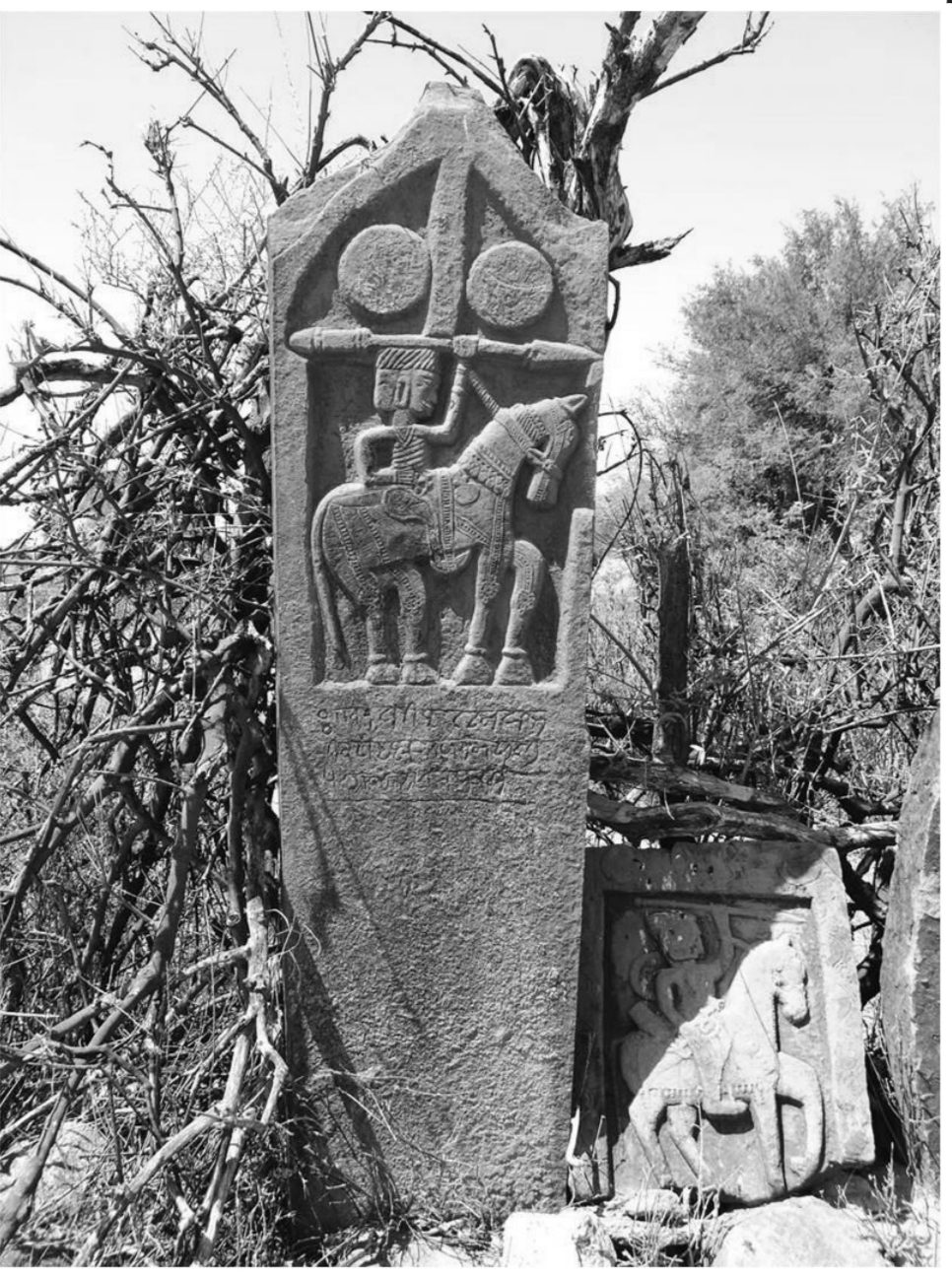

A memorial stone is a cylindrical, square or rectangular standing stone, placed facing east, and divided into two sections. The upper section features a carved motif and the lower bears an inscription. These memorial stones are erected for men who died in battle, or for women, Satis, who immolated themselves on the funeral pyre of their husbands or on hearing the news of their husbands’ death in battle. Nagarparkar, the south-eastern region of Sindh, is dotted with memorial stones erected by the Sodha who once ruled there, and other Rajput clans. These stones are objects of veneration for the Hindu community living in the area. Most have the sun and the moon carved on their upper sections. The sun is carved with distinct rays, and occasionally has a human face, while the moon may be represented either full or crescent-shaped and recumbent. The interpretation of these carvings, according to the locals, is that as long as the sun and moon remain, these people will be remembered – thus symbolizing eternity. The cult of Sati- and hero-worship is prevalent in Nagarparkar even today. Sati-memorials sometimes have depictions of naked arm or an armful of bangles. At times, the images of both a Sati and her husband are seen on the same stone. The husband is shown as a mounted warrior on a horse while Sati stands on his right with her hands joined; others hold a pot or other object.

One also comes across hero-stones depicting camel riders, and these invariably belong to the Rabaris, also a Hindu community. Many monuments depict a hero fighting with cattle-thieves and enemy troops. Cattle-raiding was a frequent and favorite sport of aspiring heroes. It was considered a demonstration of power and bravery to seize the cattle of rival tribes. Those who died while defending their homeland against foreign occupation, or their cattle and community and village resources, were called Vir, Jhujhar Soreh or Sarfarosh. (Continues)

_________________________

About the Author

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro, PhD, is an anthropologist and assistant professor at the department of Development Studies at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad. This essay was collated by Saaz Aggarwal with extracts from several of his Friday Times columns, and includes excerpts from his forthcoming book Saints, Sufis and Shrines: A Journey through the Mystical Landscape of Sindh. Dr Zulfiqar has been exploring and writing about the less-known and unknown heritage of the subcontinent since 1998, when he was a student of Anthropology at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Dr. Zulifqar is a ‘Khanani’ Kalhoro, descended from Muhammad Khan Kalhoro, son of Yar Muhammad Kalhoro, founder of the Kalhora Dynasty which reigned from 1700 to 1718.

All photographs in the essay were taken by him. He can be reached on zulfi04@hotmail.com.

The author has shared his article published in Indian scholar Saaz Aggarwal’s book ‘Sindh Tapestry- Reflections on Sindhi Identity: An Anthology’.

The author has shared his article published in Indian scholar Saaz Aggarwal’s book ‘Sindh Tapestry- Reflections on Sindhi Identity: An Anthology’.