To promote peace in the subcontinent, India and Pakistan should think of ideas for positive engagement. Collaborative academic projects and exchanges of students and academic experts can provide a conducive environment for resolution of the larger and much more complex issues of peaceful co-existence.

Hemant Rajopadhye

The national identity of Pakistan is rooted in the ‘two-nation theory’—the very basis of the creation of the country—which says that the Hindus and Muslims of the subcontinent were two different nations and therefore, the Muslims were entitled to a separate homeland where Islam would be practiced as state religion. Does Pakistan’s quest for identity, however, mean neglecting the non-Islamic culture present in the country? This brief calls attention, for example, to the Hindu temples and shrines in various parts of the country that now stand in a state of disrepair. It argues that Pakistan must work with India to rediscover and celebrate their shared cultural heritage and syncretic past; this will, in turn, help end mutual hostility and distrust.

Introduction

In November 2017, Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar expressed serious concern over the state of the ancient Katas Raj temple complex – one of the most revered Hindu places of worship in Pakistan’s Punjab province. He took suo motu notice of the news reports about the drying up of the sacred pond in the middle of the complex and asked for a comprehensive report from various state agencies. Indeed, the revival of old and dilapidated Hindu temples has been a contentious issue in Pakistan in the past couple of decades.

The Katas Raj complex has several ancient temples dedicated to Shiva, Ram and Hanuman. The Shiva temple is considered one of the most sacred and finds mention in the Mahābhārata. The Pandavas are believed to have spent a considerable part of their exile there. The pond at the center of it is thought to have been created by the teardrops of an inconsolable Shiva as he flew across the sky carrying the dead body of his wife Sati.

Katas Raj, however, is sacred not only for Hindus. The Archaeology Department of Pakistan has found and registered many Buddhist and Sikh shrines of religious and historical significance in and around the temple complex. In spite of such a rich legacy, however, Katas Raj had remained in obscurity after Partition of 1947, until then Deputy Prime Minister of India L K Advani visited the temple complex during his trip to Pakistan in 2005. The visit received wide publicity in Pakistan and led to two significant developments: the government of Pakistan started the restoration of the Shiva temple, and also invited Hindu pilgrims from India to celebrate the shivratri there. In 2007, Pakistan even sent a team of archaeologists to India to brief Advani about the state of restoration work, which was supposed to be completed in three years.

These friendly overtures did not last long and in 2011, entry to the shrine was prohibited following the assassinations—carried out by fundamentalists—of Salman Taseer, Governor of Punjab and Shahbaz Bhatti, a Catholic leader and minister of minority affairs. The two were strong advocates of the anti-blasphemy laws and minority rights in Pakistan. These assassinations were seen as a serious setback to the status and rights of the minority communities in the country. As Haroon Khalid, a journalist and author writes, the Hindu pilgrims who assembled at Katas Raj to celebrate the shivratri that year were thrown out by local fundamentalist groups. The restoration work of the temple complex was abruptly stopped.

Things took a turn once again in January 2017 when the repair work for the temple was re-launched by then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif with great fanfare as a “symbolic gesture to reach out to the Muslim nation’s minority communities and also soften the country’s hardliner image abroad.” The Katas Raj temple’s long-winded restoration, in fact, may be viewed as a metaphor for the overall state of India-Pakistan relations —in the same way as the celebrations of other Hindu and Sikh festivals in Pakistan. For example, during the term of Pervez Musharraf, the public celebrations of Basant Panchami (or the festival that marks the arrival of spring) and Holi (the festival of colours) were banned in Pakistan in 2005, when bilateral relations hit a low. The ban was lifted as relations improved, and in 2017 Nawaz Sharif personally participated in the celebrations.

The State of Non-Islamic Religio-Cultural Shrines

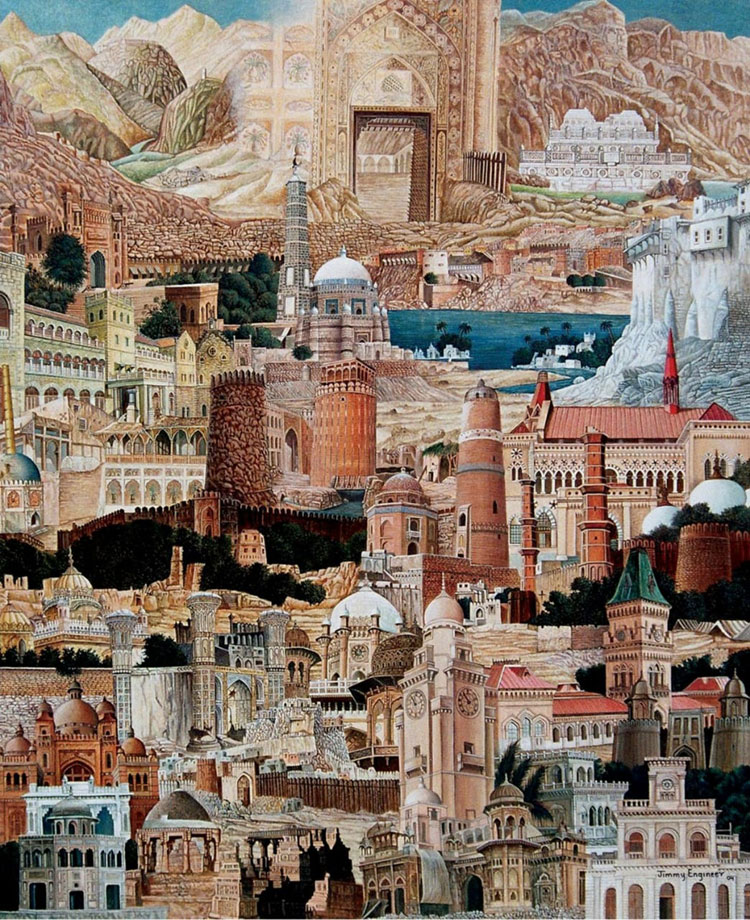

Apart from the Katas Raj complex, there are many other important Hindu shrines in Pakistan, such as the Sun temple and Prahladpuri temple in Multan, Shri Varun Dev Mandir in Karachi, Hinglaj Mata temple in Balochistan, and the Kalka Devi cave and Sadhu Bela temple in Sindh. There are many Jain and Buddhist shrines as well. All these shrines, however, have been largely neglected—deliberately or otherwise—by a succession of civil and military regimes.

It is difficult to get accurate details about non-Islamic heritage structures in Pakistan because there are only few available academic texts on the subject. A few articles in the mainstream media, web sites, social media pages, and scattered pieces of academic references on broader themes are all that exist to provide some idea about these structures, their state of disrepair, and the overall erosion of cultural diversity in Pakistan.

The violence that accompanied the partition of the subcontinent in 1947 had made the Hindu and Sikh places of worship in Pakistan, targets of extremist attacks; it was the same case with mosques in India. However, antipathy towards the religious structures of the Buddhist, Jain and Christians became more pronounced after the demolition of the Babri masjid in India by right-wing Hindu fundamentalists in December 1992. That event, perhaps for the first time after Partition, triggered extreme and massive anti-India and anti-Hindu sentiments in Pakistan. Enraged Muslim fundamentalists demolished a large number of Hindu and other non-Hindu shrines and relics. One example is that of a historical Jain Mandir near the famous Anarkali Bazar of Lahore’s old city. It was damaged by a mob after the Babri masjid demolition and then later used for commercial purposes. According to some Pakistani media reports, a part of the old mandir was also used as a madrasa.

The temple was razed to the ground along with other historical heritage structures such as the Meharunisa tomb and the St. Andrew’s church by the Punjab government in February 2016 “to pave a way for the controversial project of Lahore Metro line.” These demolitions were carried out despite a Lahore High Court’s order to suspend all work on the line within 200 feet of buildings of historical value. A few years earlier, the Punjab government had promised to restore the same temple. Across Punjab, many other Jain shrines have been neglected, as is the case with many Buddhist sites in the North West Frontier Province (now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

According to the Pakistani media, Lahore’s Jain temple was destroyed as the Muslim fundamentalists did not differentiate between Hinduism and Jainism. Many such incidents and records of complex religious identities, temples and other Hindu, Jain, Sikh and Buddhist structures have been documented and discussed by some anthropologists and journalists in Pakistan.

Various scholars trace the history of Jainism in the Indus Valley back to the era of Alexander the Great, though there are those who disagree. In popular culture, the ascetics whom Alexander is said to have met were Jains residing in the ancient university town of Takshashila (now Taxila), near Islamabad. Some of Pakistan’s intelligentsia believe that the Jains ruled the region for several centuries, before the rise of Hinduism. Veteran Indologist Dr. R. G. Bhandarkar mentions two major Jain manuscript libraries in Gujranwala, Punjab, which record the rich tradition of Jain scholarship in the region.

The Decimation of Everything ‘Indian’ and ‘Hindu’

The genesis of the anti-non-Islamic sentiment, and the targeting of shrines belonging to non-Islamic religions considered as ‘Indian’—such as Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism—is rooted in the same principles that founded Pakistan as a nation state in 1947. Pakistan was created on the basis of the ‘two-nation theory’ which states that the Hindus and Muslims were two different nations, and therefore, the Muslims were entitled to have a separate homeland in the pockets of their majority where Islam would be the ‘state religion’.

Although, the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had conceived of creating a non-theocratic state, his political successors declared Pakistan as ‘Islamic’ in the first Constitution adopted in 1956, paving the way for all laws to be brought in conformity with the Qur’an and Sunnah. In the second Constitution, adopted by the military dictator Mohammd Ayub Khan in 1962, the word ‘Islamic’ was removed but was soon re-inserted following a civil backlash. The nation-state saw forcible conversion of the Hindus in Sindh, atrocities committed on the Christians and Ahmadiyyas, and various attempts to portray India and the Hindus as enemies of Pakistan. These developments helped religious nationalism to thrive in the country.

Veteran historian of Pakistan, KK Aziz, discusses these themes in his book, Murder of History: A Critique of History Textbooks Used in Pakistan. Some of the most relevant excerpts are the following (with this author’s comments in brackets):

“Either to rationalize the glorification of wars or for some other reason(s), the textbooks set out to create among the students a hatred for India and the Hindus, both in the historical context and as a pan of current politics. The most common methods adopted to achieve this end are:

To offer slanted descriptions of Hindu religion and culture, calling them “unclean” and “inferior”.

To praise Muslim rule over the Hindus for having put an end to all “bad” Hindu religious beliefs and practices, and thus, eliminated classical Hinduism from India. (Both claims are false.)

To show that the Indian National Congress was a purely Hindu body that it was founded by an Englishman, and that it enjoyed the patronage of the British government. From this, it is concluded that Indian nationalism was an artificial British-created sentiment. This is done with a view to contrasting alleged false colors and loyalty of the Congress with the purity and nationalistic spirit of the All India Muslim League. (This will be discussed more in latter parts of this brief.)

To assert that the communal riots accompanying and following the partition of 1947 were initiated exclusively by the Hindus and Sikhs, and that the Muslims were at no place and time aggressors but merely helpless victims.

To allot generous and undue space to a study of the wars with India.”

According to some reports, before 1975, the school textbooks in Pakistan did in fact teach the pre-Islamic past of the region. The reports provide some suggestions and advice to Pakistan’s textbook committees which would help reduce “the pathological hatred towards Hindus”. Some of the recommendations made in these reports are:

The early history books contained chapters on both the oldest civilizations Mohenjo Daro, Harappa, Gandhara, etc., but also the early Hindu mythologies of Ramayana and Mahabharata and extensively covered, often with admiration, the great Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms of the Mauryas and the Guptas.

The textbooks indeed showed biases when discussing the more recent history of the politics of independence, but still one found school textbooks with chapters on Mohandas K Gandhi, using words of respect and admiration for the Mahatma.

Even in the somewhat biased history of politics of independence, the creation of Pakistan was reasoned on the intransigence of the All-India Congress and its leadership rather than on ‘Hindu machinations’.

Some books also clearly mentioned that the most prominent Islamic religious leaders were all bitterly opposed to the creation of Pakistan.

“Such was the enlightened teaching of history for the first twenty-five years of Pakistan, even though two wars were fought against India in this period. The print and electronic media often indulged in anti-Hindu propaganda, but the educational material was by and large free of bias against Hindus.

“Then came the time when Indo-Pakistan History and Geography were replaced with Pakistan Studies, and Pakistan was defined as an Islamic state. The history of Pakistan became equivalent to the history of Muslims in the subcontinent. It started with the Arab conquest of Sindh and swiftly jumped to the Muslim conquerors from Central Asia.”

Parallels in India

Yet, a similar situation exists in India. For example, Maharashtra’s history textbook for the eighth grade says Dr. Mohammad Iqbal proposed the idea of a separate homeland/nation for the Muslims of India that was endorsed and conceptualized by Jinnah. On the other hand, the NCERT textbook contains more facts and theories about the two-nation theory.

A series of recent incidents in India may not exactly mirror the events in Pakistan, but they do point to a growing tendency to portray everything associated with Pakistan as “evil”. Over the past four years, a growing intolerance towards India’s minority communities has manifested in various ways: mob lynching to “protect” cattle and punish beef consumption, harassment and violence in the name of so-called “love jihad”, and “gharwapsi” campaigns. The fracas over the portrait of Jinnah in the Aligarh Muslim University is also evidence of how radical elements in India are trying to paint everything “Pakistani” as unwanted and constitute a threat to everything “Indian”.

These incidents, if unchecked, can potentially inflict deep wounds to the social fabric of India. This pluralist ethos, after all, has long been the pillar of India’s unique civilizational, multi-religious and multi-cultural harmony.

The bloody legacy of Partition has created a massive identity crisis in both Pakistan and India. The imagined nationalities propounded by the architects of the two-nation theory have wiped out the memories of their ancient, shared past and culture. After Partition, the immediate military incursions in Kashmir, followed by two wars and the Kargil conflict – which bred a hyper nationalistic fervor in both countries – led to an increasingly bitter political relationship. This has impacted both peoples’ perception of the other. It is in this context that it becomes imperative to make the people of both countries aware of their shared heritage from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, including those of the Buddhist and Jain pasts.

Rediscovering Shared Culture as a Path to Peace

The distortion of history in Pakistan’s textbooks can be corrected by restoring its pre-1975 curriculum policy. There is hardly any school or institution in Pakistan that teaches the pre-Islamic history of the subcontinent/country. In the last few decades, most of the native historians of Pakistan have been discussing the post-Partition history; only a few are engaging critically with the ancient and medieval past of the region. There are a few voices who raise arguments against the policy of denying the syncretic cultural past of the country. Such voices, however, are often ridiculed as “fashionable progressivism”.

Unfortunately, the situation is not very different in India. Every call to foster closer ties between the people of the two countries or seek to rediscover their shared past have been met with contempt and, at times, violent opposition from right-wing hardliners.

As a result, most contemporary Indians and Pakistanis are not aware of the fact that the historical geography of the Rigveda, the foremost of the Vedas and one of the holiest books of the Hindus, is located in the region of what is called Pakistan today. The great Sanskrit grammarian Panini was born in today’s Charsadda, near Peshawar (ancient Purushpur or Pushkalavati) and spent his life in Shalatur, which is now known as Lahore. The great political thinker Chanakya was a teacher at the Takshashila University. The great Buddhist emperor Ashoka was the governor of Takshashila province before his coronation. Kaikeyi, the mother of Bharat, step-brother of Lord Rama, was from the Kaikeya region, which is today a part of Pakistan’s Punjab. One can give many other such references from the ancient Hindu, Buddhist and Jain texts which are an indivisible part of the shared history of India and Pakistan.

At the same time, and fortunately, there is the shared heritage that continues to be cherished in both countries. For example, the Nankana Sahib in Pakistan’s Punjab, the birth place of Guru Nanak, remains one of the most revered places of pilgrimage for the Sikhs in India. Hundreds of Indian Sikhs visit the gurudwara near Lahore every year. Similarly, the dargah of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti at Ajmer in Rajasthan continues to draw hundreds of pilgrims from Pakistan.

Indeed, as India and Pakistan look forward to celebrating their 75th year of independence in 2022, the two countries should collaborate to mark that year as one of rediscovery of their shared culture and history. For example, institutions of higher learning can help create an environment of mutual trust by carrying out joint research, and designing academic courses relating to the classical languages, scripts and cultures of the subcontinent. These institutions should also facilitate joint exploration of archeological sites of multi-religious importance.

The academe must be encouraged to design courses for students from both countries to learn languages such as Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Urdu, Persian and Arabic. Joint studies of ancient scripts such as Brahmi, Kharoshtri, Sharada (ancient script of Kashmir) and different variants of Nagari scripts without which, one can never read the inscriptions and manuscripts written in ancient Sanskrit, Prakrit and Pali languages—must also be encouraged. Similarly, religious studies in both countries should be designed to enlighten students about the great syncretic culture that flourished in the subcontinent.

Making people rediscover their identities through academia is a constructive way of helping end mutual hostility and distrust. This is equally important as other peace initiatives such as composite dialogue. At the same time, both governments should promote large-scale, cross-border religious tourism which has been repeatedly mentioned in official joint statements but never acted upon.

Conclusion

The resurgence of religious intolerance and animosity in both Pakistan and India can be abated by rediscovering and celebrating the shared legacy and syncretic past of the subcontinent. After all, there is nothing exclusive about the shared culture and heritage of the two nations. It is owned by the Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and Muslims alike. A distorted and biased understanding of these shared cultural values and heritage is as much a problem of the national identity of Pakistan as it is of India. What is required to overcome it is an openness to accept history in its raw and undistorted form.

A joint academic program or policy focusing on the shared civilizational past of the subcontinent can be one of the least difficult ways to prevent the spread of the politics of false propaganda and biased identities created by the communal forces in both countries. Veteran Pakistani journalist and thinker Hasan Nisar once famously said, “Jo qaum apne tareekh ko masq kar deti hai, tareekh use masq kar deti hai” (A society that destroys its own history gets destroyed by history).

To promote peace in the subcontinent, India and Pakistan should think of such ideas for positive engagement. Collaborative academic projects and exchanges of students and academic experts can provide a conducive environment for resolution of the larger and much more complex issues of peaceful co-existence.

[Reloaded as the original file was destroyed due to database error]

_____________________

Hemant Rajopadhye was a Senior Fellow and Head of ORF Mumbai’s Centre for the Study of Indian Knowledge Traditions. His research focuses on what the subcontinent’s socio-political and cultural history and traditions offer to understand the solutions to today’s local, national and subcontinental problems, interfaith harmony, and pluralism, and social justice, cultural, religious and linguistic conflicts.

Courtesy: Observer Research Foundation