The Company looted and put on auction all the public and private property including gold and silver, furniture, crockery, all the household items, beds, bed-covers, children’s cots, and even the children’s and ladies’ finished and unfinished garments.

‘Annexation and the Unhappy Valley – The Historical Anthropology of Sindh’s Colonization’ is the latest edition of the book authored by Matthew A. Cook, published recently by Oxford University Press Karachi. It was first published in Netherlands in 2016.

This is a very important and informative research book on history of Sindh starting from arrival of British traders, upto the conquest of this country in 1843 and afterword. The book has mainly four chapters – Merchants and the East India Company in Sindh, Conspiracy and Military-Fiscalism, Just Governance and Colonial Violence, and the Court over Board.

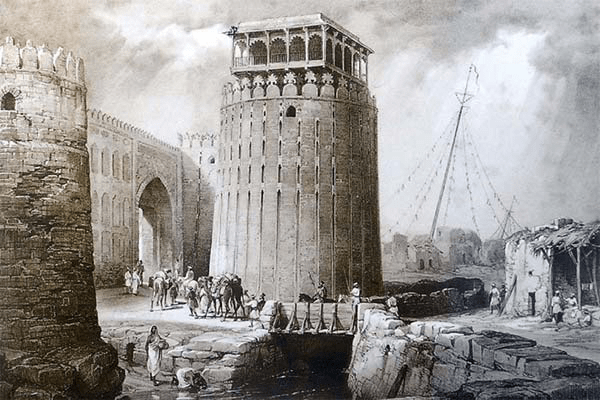

The chapter ‘Just Governance and the Colonial Violence’ contains the account of how the East India Company plundered Sindh. One of its subchapter is titled as ‘The Plunder of Hyderabad’, which, according to author, was on grander scale.

The book introduces the reader to a story that is still not sufficiently well-known or well-understood. Cook is meticulous in his excavation of official and non-official archival material collected in London and from different parts of South Asia (e.g. Maharashtra and Sindh). Drawing on official documents alongside handwritten commentaries, notes and more personal sources, he shines the spotlight on a large quantity of interesting discursive material and accompanying debate, linked in various ways to an “infamous” episode in the expansion of British power in South Asia.

Few historians have written, and (as far as this reviewer is aware) no historical anthropologists have previously attempted to work, with such close attention to their sources, on the developments. Certainly, for this reason alone, Annexation and the Unhappy Valley represents a welcome and long-overdue concerted effort to dissect and discuss with forensic intensity the “anatomy” of the fall-out from Sindh’s annexation in the years and even decades that followed.

Here are excerpts from this chapter.

The Company occupied Hyderabad in 1843. Over the next two years, it looted substantial amounts of property from the city. The Company’s accountants measured this plunder at over 4.5 million rupees. A financial review of Sindh by the Governor of Bombay in 1848 put this sum in context: It was significantly greater than the annual revenue receipts for every year that Napier ruled Sindh.

After the Company sold the Gold and Silver that it looted, Bombay’s Accountant General reported that the value of Sindh’s plunder increased to over 4.7 million rupees. This sum did not include profits from plunder that the company sold in Sindh, which exceeded 4.7 million rupees.

While it was common for the Company to claim ‘prize property’ from defeated enemy, the types of items that Napier sent to Bombay for sale gave insight into British behavior in Sindh. The content lists of these items were full of personal objects: women’s anklets and necklaces, earrings, finished and unfinished Korans (Qurans) and prayer books, books with and without dust-covers, and even a text listed as ‘old nothing in particular’. Like many who plunder, the Company’s agents failed to differentiate private from public property.

In a letter to the prize agent Major Blenkins, Captai A. B. Rathbourne, the Collector of Hyderabad, justified the Company’s failure to distinguish between private and public property by incorrectly maintaining that no such difference existed in Sindh. He also maintained that a great proportion of Hyderabad’s public wealth was in private quarters of women. He wrote that the Ameers’ wives and concubines defrauded the Company by deliberately conflating public and private property.

Despite Rathbourne’s description of women secretly carrying off state property, the other officers reported that almost no item escaped confiscation by the Company. In March 1843, John Jacob made several visits to a many months-long auction organized by the Company. Rather than horses for his regiment, Jacob found personal items for sale:

“On these occasions I saw among the prize property a great number of pieces of silk embroidery and such like. Many of these pieces were half finished with needles still in the work. I also saw there [at the auction] ladies’ work baskets and boxes, large heaps of ladies’ dresses and oriental female attire of all sorts, infants’ clothing, immense quantities of furniture, crockery, ladies’ bedrooms and toilets, beds, beddings, carpets, children’s cots, together with all manner of other household furniture of sorts in great quantities. These had evidently been in use by their late owners immediately before they were seized and exposed for sale by prize agents at public auction.”

About the auction, Jacob wrote that he was heartily disgusted with the whole proceeding, and that it was result of robberies. He maintained that there should be a strict line between public and private property. He thought it particularly undignified for the Company to confiscate the personal items of women and children:

“I vehemently argued that no conquest have any right over the private personal property of individuals, much less over that of women and children. It was a shame to strip poor ladies of their furniture, dresses etc.”

In a Victorian spirit, Jacob criticized how prize agents treated women when they refused to allow a pregnant noble to purchase her favorite bed:

“To such an extent was carried the meanness and atrocity displayed in collecting of prize property at Hyderabad that when one of the ladies of Meers expecting shortly to be confined in childbed, wished for a favorite bed of hers which had been seized with rest of the prize property, sent one of her followers to ask the agents to let her have it, her request was refused.”

Jacob stated that the agents searched everyone: “The slaves, attendants etc. who went out of the fort were all searched and nothing could escape the hands of searchers.” To search women, the agents employed a ‘common prostitute’ who according to Jacob, conducted her job without any regard to decency. Jacob wrote that women in Hyderabad so greatly feared sexual assault by Company officers that they simply distributed their personal property freely:

“The proceedings described above almost frightened the ladies to death and when anyone went toward their apartments a servant or follower rushed out to offer him jewels, trinkets or such like. The poor things always feared that they were about to be seized and stripped.”

Napier’s supporters (J. W. Younghusband and others) disputed Jacob’s claim that the prize agents indecently searched women and sold their personal items. However, the private letters by many Company officers did not vary from Jacob’s account. About searching women, Dr. Mackenzie, a Company Medical Officer, in a letter wrote:

“They [Prize Agents] employed a woman to examine the women as they were leaving the fort, not only externally but about their private parts. It was shameful piece of business and I suspect they themselves are averse to tell all that took place.”

However, Dr. Mackenzie disputed Jacob’s assertion that the agents searched noblewomen.

Deputy Collector of Hyderabad also challenged Jacob that noblewomen were searched however he admitted that their women servants were all searched by the whore.

Many other officers including Lt. Col. Edward Green, Adjutant General in Sindh, maintained that prize agents searched every woman who left the Hyderabad. No private letters denied that a whore was deployed for searching the women. Neither these letters contradicted how the prize agents confiscated and sold personal items. Richardson and McGregor both wrote that the women’s apparel – saris, cholis, shawls and pajamas, was a particularly big auction item for the Company. Richardson wrote that the apparel for sale was in all of stages of completion: In addition to new and completed garments, the Company sold half-manufactured clothes, unstiched outfits and items that were old and worn.

Many other officers including Lt. Col. Edward Green, Adjutant General in Sindh, maintained that prize agents searched every woman who left the Hyderabad. No private letters denied that a whore was deployed for searching the women. Neither these letters contradicted how the prize agents confiscated and sold personal items. Richardson and McGregor both wrote that the women’s apparel – saris, cholis, shawls and pajamas, was a particularly big auction item for the Company. Richardson wrote that the apparel for sale was in all of stages of completion: In addition to new and completed garments, the Company sold half-manufactured clothes, unstiched outfits and items that were old and worn.

McGregor also reported the same saying he saw big quantities of women’s clothing, new and old, put on sale. He writes:

“The ladies themselves knew their clothing was being sold by auction and looked with scorn on the transaction. They said, ‘Our Gold and Jewels were your lawful prize but why sell women’s garments’. They made such remarks to my wife when she went to visit them as she frequently did.”

In addition to women’s garments, the Company plundered and sold a whole range of domestic items. Richardson bought plows and bedding but also observed the auction of chairs, beds, stools, swings and worn-out carpeting. About the auction, he wrote: Scarce an article of household furniture can be named that was not to be found there. In addition to garments and furniture, the Company also sold crockery.

McGregor reported that the prize agents sold everything from ‘handsome china to the commonest stoneware’. Richardson confirmed the Company’s sale of teapots, basins, plates, cups and saucers. He described how the prize agents conducted a weekly crockery sale:

Sale of glass crockery etc. was held once a week outside the fort, where might be purchased such articles from the splendid china bowl to the humble white delf- chamber utensil.

Richardson concluded that the range of domestic items for sale was so vast that it was difficult for him to name an article of either Indian or European manufacture that was not represented. In a letter to John Jacob, Lt. Col. Green explained the source of the domestic plunder that Richardson and McGregor marveled at:

From my own knowledge, the entire contents of the Meer’s houses in the Zenana Khanna were exposed for sale, carpets, clothes, pillows, bed-covers, crockery, glass and in short the whole economy of the house.

After the Ameers’ wives and concubines departed Hyderabad, Green wrote that the Company entered their quarters, emptied them and auctioned their contents. Like C. W. Richardson and J. McGregor, Green was similarly astonished at the number of goods for sale. He was particularly flabbergasted by the diversity of looted crockery: Almost all the Zenana Khanna houses had rows of niches all around the walls crammed with glass and china of all descriptions, the marvel being where it came from.

____________________