Why Indian Sindhis hold Karachi especially dear? The name of the Karachi chain of sweets and bakeries has frequently come under attack for its seeming association with Pakistan. Yet, for the Sindhi owners of the chain, the name is a reminder of a lost homeland and a Partition unlike any other.

Why Indian Sindhis hold Karachi especially dear? The name of the Karachi chain of sweets and bakeries has frequently come under attack for its seeming association with Pakistan. Yet, for the Sindhi owners of the chain, the name is a reminder of a lost homeland and a Partition unlike any other.

By Adrija Roychowdhury

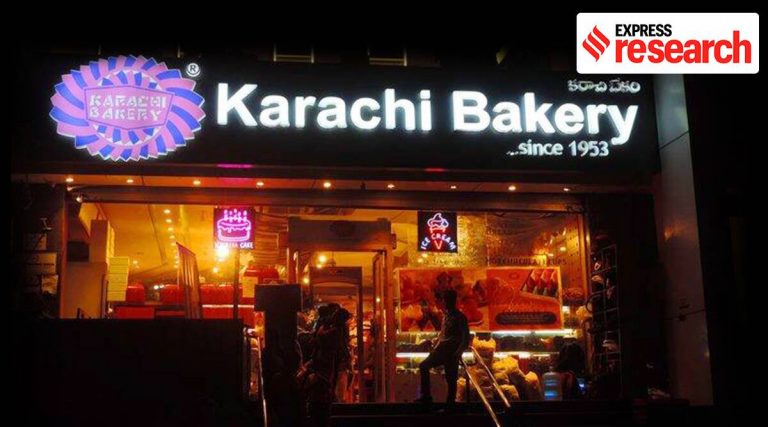

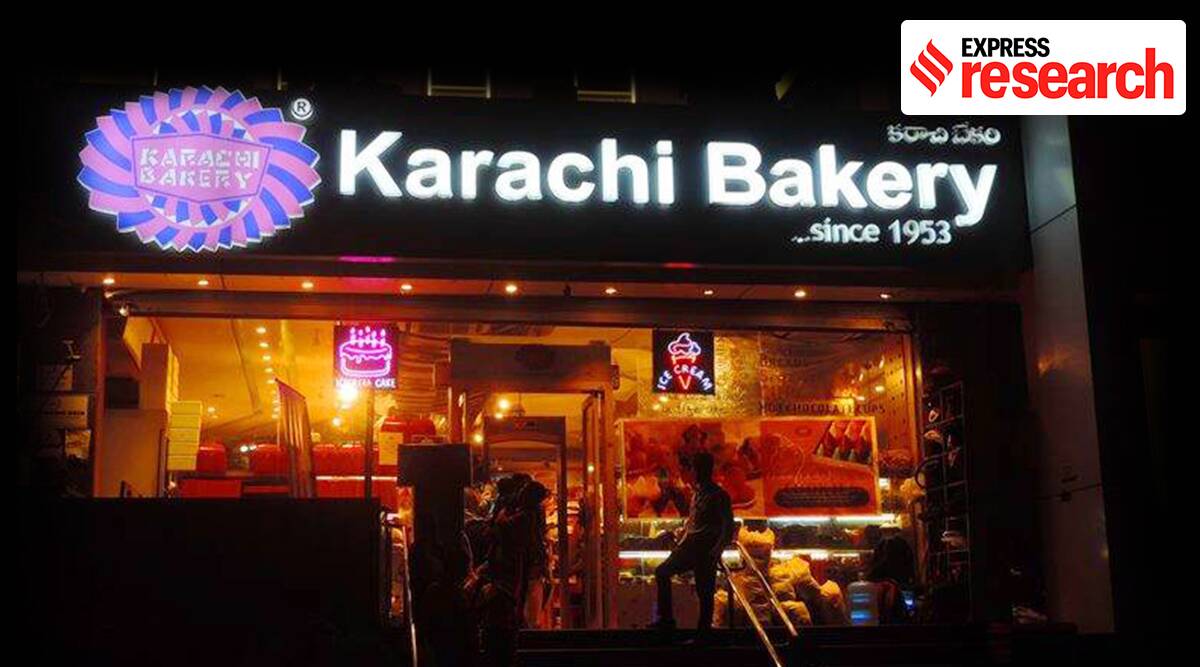

Rajesh Ramnani does not take even a second to respond when asked why Karachi is important to him. “It is a reminder of all the emotions, sacrifices and hard work that our elders went through in order to create this brand, far away in a distant land,” says the 43-year-old, one of the directors of the much-loved Karachi Bakery that was started by his grandfather, Khanchand Ramnani after he migrated to Hyderabad (India) from his home in Sindh (now in Pakistan) in the wake of the Partition.

At that time Karachi was a city bustling with enterprise and opportunities, much like what Mumbai is today, explains Ramnani. His grandfather had opened a business in sweets and bakery products there and had named it after his beloved city. With the Partition, the bakery was uprooted, and so was the life and dreams of the senior Ramnani who fled in the midst of bloodshed and violence to build a new home first in Ajmer and then in Hyderabad, where he once again established the bakery with the same name.

Ramnani recollects the many conversations he had had with his grandfather about the days when he migrated to India. “He saw people cutting each other with swords, tearing them apart,” he says. Ironically, he says despite the bloodshed and hatred of the time, nobody objected to the name ‘Karachi Bakery’.

“Why then is it being attacked today?” he asks, about a recurring controversy over the name of the bakery. The issue came up again last week (In November 2020) when a sweet shop owner in Mumbai’s Bandra West was forced to cover his shop sign with newspaper pages after Shiv Sena leader Nitin Nandgaokar wanted Karachi dropped from its name.

The name of the Karachi chain of sweets and bakeries has frequently come under attack for its seeming association with Pakistan. Yet for the Sindhi owners of the chain, the name is a reminder of a lost homeland and a Partition unlike any other.

Sindh, unlike Punjab and Bengal, was not divided. The entire territory went to Pakistan. At the same time, unlike the other communities, who found a state to their name in free India- Punjab for the Punjabis, Gujarat for the Gujaratis and Bengal for the Bengalis, the Sindhi migrants found themselves with no such land to call their own.

“They were role-model refugees, not asking for anything, not complaining, simply asking themselves the question, “Ok, what next?” and getting on with it,” says writer Saaz Aggarwal who has carried out extensive documentation of the Sindhi community in India. She adds, “In the process they contributed tremendously to the communities they settled in, a contribution that is often glossed over as having been done for mercenary reasons.”

Isolated from the rest of India

Situated right at the borders of Rajasthan and Gujarat, the territory of Sindh was closely impacted by the division of the country. Yet, the experience of Partition in Sindh was very different.

“The difference stemmed primarily from the fact that the social dynamics in Sindh was very different from the rest of the country,” says author Rita Kothari who has written several books on the impact of Partition on Sindhi identity. She explains that unlike other Partition affected parts of the country, Sindh on the eve of the Partition did not experience any Hindu-Muslim riots. “As a frontier region Sindh had a Hindu minority of 25 percent. That minority did not live in textualized forms of Hinduism that you would find in mainstream India. They were very influenced by Sikhism and Sufi practices,” she says.

Politically too Sindh was far removed from large parts of the Indian subcontinent. Long before Islamic rule came about in most regions in India, Sindh came under the rule of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 712 CE. Moreover, Sindh had barely drawn colonial attention till about the mid-19th century. It was only in 1843 that Sindh was annexed by the British from the Talpur Mirs and made part of the Bombay presidency. “Sindh was one of the last provinces to be annexed and it seemed that once the Bombay government’s interests were served, it cared little for Sindh’s development,” writes Kothari in her book “The burden of refuge: Partition experience of the Sindhis of Gujarat.”

In her paper, Kothari explains how the colonial annexation of the territory shattered Sindh’s cultural and political isolation from the rest of India, and also broke down the religious fluidity that was an intrinsic part of its landscape. Thereafter, socio-political developments happening in the rest of the country was bound to affect Sindh. “The merger with the Bombay presidency proved to be psychologically reassuring for the Hindus who were then no more a religious minority in an isolated province. It also gave them the confidence to use their capitalistic power,” writes Kothari.

Meanwhile, the Muslims of Sindh did not derive any direct benefits from the new dispensation. Consequently, an economic unrest among the Muslims emerged, manifesting itself in the formation of Muslim political organizations.

A bloodless Partition

On the eve of the Partition though, unlike its neighboring regions, Sindh remained relatively quiet. Though the territory went entirely to Pakistan, it was assumed that Hindus would not leave given that they had lived in peace as a minority for centuries. For that matter, even till August 15 no giant exodus of Hindus took place.

However, a sort of ‘nervous peace’ prevailed. “But the absence of communal violence did not mean that Hindu-Muslim relations were completely amicable in Sindh. With reports of riots and massacres from other parts of India flowing in daily, Sindhi Hindus were deeply fearful of similar violence from Sindhi Muslims,” writes author Nandita Bhavnani in her book, ‘The making of exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India.’

Finally, there was also the issue of an increasing number of Muslim refugees from India coming into Sindh. “The real mass exodus started after the Karachi riots of 6 January 1948, when Muslim refugees from Eastern Punjab started a looting spree of Hindu property in the capital of Sindh. This produced a wave of panic, which spread to all urban centers of the province,” writes historian Claude Markovits in his book “The global world of Indian merchants: 1750-1947 traders of Sindh”.

Though the violence in Sindh was nothing compared to what was happening in Punjab, Markovits explains that by mid-1948 a total of 1,200,000 non-Muslim refugees had entered India, stretching the resources of the provincial government in Bombay to the limit.

Preserving Karachi in India

Perhaps it is safe to say that Sindhis got the rawest deal in the Partition. With no corresponding space to call their own on this side of the border, they settled down wherever they could and managed to prosper and contribute as well. “I find the period after Partition much more significant in the shaping of Sindhi identity in India. They were unwanted migrants everywhere,” says Kothari. “It is at the time of rehabilitation and being refugees at that early period, when they dealt with a lot of suspicion and rejection, both by the state and the civil society. Consequently, they shed away everything that made them distinct. They assimilated more than any other community,” she adds.

This easy assimilation of the community cost them their language and culture. Aggarwal recalls that as a child she hardly knew anything about Sindh. “No one at home ever spoke about Sindh. Then there was the sense of embarrassment stemming from stereotypes created by Hindi cinema of Sindhis being cunning characters,” she recalls. So isolated was the post-Partition Sindhi from their culture, that well up till 1967 their language was not even accepted as an official language of the country.

Despite the cultural loss, the Sindhis made noteworthy contributions to the country. In Mumbai, for instance, within seven years of Partition, at least three prominent colleges were started by Sindhis which were open to all. In an attempt to build houses for themselves, many got into the construction sector. “There’s a big chunk of neglected history of Sindhi contribution to the Indian freedom movement,” says Aggarwal. Sindhi names like Hemu Kalani and Bhai Pratap are almost never remembered in text book references to the nationalist movement.

As language, culture and history slipped away, the community held firmly onto the memories of the streets of Karachi, Hyderabad (Sindh), Shikarpur, Sukkur and Larkana. It was but natural for them to name their businesses after the lost homeland. “Hindu Sindhis have no attachment to the province of Sindh in Pakistan. Their allegiance is to the ancestral homeland of Sindh, which they lost at Partition and to their essential Sindhiness. The names are a link to an emotional connection that was snatched away and never even mourned,” says Aggarwal. “What else have they got apart from some memories, some names of the land they left behind and a few food items?” asks Kothari.

If the name Karachi symbolized memory of homeland for the Sindhis, then the demand to change it is seen as an insult to the years and efforts they have given to the development of India. “We have been serving this country since the time of Independence. Then why do we have to prove ourselves today?” asks Ramnani. “A lot of blood and sweat has gone into creating Karachi Bakery as a brand. People have grown up with fond memories of our biscuits. All of this cannot be changed overnight.”

_______________________

Very true picture of partition sir. My father used to tell that we left Sindh because of Punjabi, Bihari muslims who migrated to Sindh. We were loved by our muslim sindhi brothers. You have rightly said that Hindu sindhis of India have conveniently forgot Hemu Kalani and Bhai Pratap. Hemu Kalani family is staying in Chembur Mumbai where I live. Bhahi Pratap is known only to sindhis living in Adipur and Gandhidham of Gujrat. In Mumbai locals are jeolous of prospering sindhi community hence we suffer. Karach will remain in our hearts for ever.