The Hakka people are generally identified as indigenous people of northern China, who are now widely scattered throughout southeastern China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia

Ashraf Aboul- Yazid

It does not seem to me that there is anything more representative of human history than poetry. It is true that narration has a broader horizon, greater freedom in formulation, and a more comprehensive ability to record numbers and statistics in addition to biographies and narratives. However, poetry remains the most truthful mirror as it is the voice of man himself.

It does not seem to me that there is anything more representative of human history than poetry. It is true that narration has a broader horizon, greater freedom in formulation, and a more comprehensive ability to record numbers and statistics in addition to biographies and narratives. However, poetry remains the most truthful mirror as it is the voice of man himself.

The ability of poets is evident in that this voice is an echo of their nation, an embodiment of its history, and that they have carved their alphabet with the chisel of art from the stone of that legacy.

Hence, I find that the Hakka poem and its poets have succeeded, together, in planting a forest of ideas that have sprouted to express the earth and man together. And the best represented by these voices in the anthologies in your hands

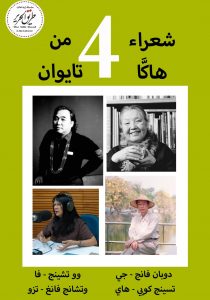

In this project, in which I present to the Arab reader four poetic voices from Taiwan, Du Pan Fang-ge, Tseng Kuei-Hai, Wu Ching-fa, and Fang-Tzu Chang, I aspire that my book will serve as a gateway to the vast world of this small island that holds on its land, there is a heavy history that does not lack pain and hopes.

Taiwanese literature and Hakka culture

In a study written by Ku Cheng Tu in in the Journal of Taiwan Literature (No. 19), we read how the historical ethnic division in Taiwan society was between the Han people (the Chinese, now the overwhelming majority) and the indigenous people. The Han people themselves consist of two main groups: Hoklo and Hakka. There are four million Hakka in Taiwan, about a third of the total population. Since the Hakka are the second largest ethnic group, their culture is, of course, an important part of the cultural landscape in Taiwan. Especially in literature, most of the writers of great novels are Hakka, which is a source of great pride for them.

Since the Hakka people are a minority in Taiwanese society, they are often referred to as “invisible people” because they do not speak the Hakka dialect in public and often try to hide their ethnicity

Since the 1980s, with the progress of Taiwan studies and the “return to the mother tongue” movement aimed at a multicultural society, academic attention has been paid to the study of Hakka language and culture, which has yielded significant research results. The Hakka culture as reflected in the literature, as well as the distinctive characteristics of their customs, languages, religion, migration histories, life experiences, and creative styles, are all worthy of research and translation to make them accessible to academics and critics abroad. Through these literary works, interested readers will gain a better understanding of Taiwan society with its multicultural complex resulting from multi-ethnic voices and languages.

Except for the indigenous people, Taiwan is an immigrant society. Han people are immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong. According to the census conducted in 2001, the population of Taiwan is 22,350,000, of which 98% are Han Chinese. And, the current population of Taiwan is 23,936,863 (April 19, 2023), based on the Worldometer’s latest United Nations data.

Who are the Hakka people?

They are generally identified as originally people of northern China, who are now widely distributed throughout southeastern China, in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia. The English word “Hakka” comes from the Cantonese pronunciation of the Chinese characters “kejia,” which means “settlers in a strange land” or “residents.”

According to historical documents, at the end of the Western Jin Dynasty (early 4th century), a group of Han people moved from the Yellow River Valley south of the Yangtze River to escape the ravages of war. Back in the late Tang Dynasty (end of the 9th century) and end of the Southern Song (end of the 13th century), a large number of people crossed the Yangtze River and moved to Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong, where they were called “Hakka” to distinguish them from the original locals. At the end of the seventeenth century, the Hakka continued their migration trend and sailed across the sea to Taiwan.

The Hakka language and traditional culture were diluted and difficult to transmit, and ethnic consciousness was relatively diminished

Since the Hakka people are a minority in Taiwanese society, they are often referred to as “invisible people” because they do not speak the Hakka dialect in public and often try to hide their ethnicity. On the other hand, the Hakka have a very strong sense of ethnic consciousness, seeing themselves as contemporaries of the culture of the Central Plains of China, and attaching importance to tradition, culture, ancestral homeland, principles from ancient times, history, family heritage of part-time study and part-time farming as indicators of their collective consciousness.

These two traits, their ethnic conservatism and their racial pride, seem contradictory, but in fact, they have proven to be effective means of integration for economic survival as a historically minority in competition with the Hoklo.

Professor Hsü Cheng-kuang aptly explains the reasons why the Hakka strive to hide or keep their ethnic identity ambiguous:

(1) Geographically: In the history of migration to Taiwan, those who came from Guangdong at a later time, the proportion of the population was smaller, and most of the agricultural areas available were along the mountains or on the slopes of the hill, relatively unfavorable to farming.

(2) Historical: In the major anti-government incidents during the Qing Dynasty, particularly the Zhou Yigui Incident in the Kangxi era (1662-1722) and the Lin Shuangwen Incident in the Qianlong era (1736-1795), the Hakka Dynasty assisted the Manchu government in putting down riots. They made themselves national subjects of the regime.

(3) Political: To consolidate the regime, political leaders often resorted to ethnic confrontations and conflicts. The “oath” [national subjects] is a historical marker engraved in the minds of the Hakka, or considered their “original sin”, so they choose to rely on the system, identify themselves with other ethnic groups, or conceal their Hakka identity to avoid any ethnic conflict.

(4) Socially and Economically: Due to environmental differences in settlement areas, most Hakka relied on agriculture and agricultural work while most Hoklo dealt with business, trade, and industrial production, resulting in significant differences in financial resources and economic status. In modern society, the Hakka moved from the countryside to the city, and in order to adapt to urban life and industrial society, they inevitably lost their ethnic consciousness and became assimilated.

(5) Languages and Cultural Policies: Both the imperial subjects movement towards the end of Japanese rule and the mainly colonial “national language” education of the nationalist government in Taiwan focused on the official language, the rejection of other indigenous languages, and the suppression of national culture.

As a result, the Hakka language and traditional culture were diluted and difficult to transmit, and ethnic consciousness was relatively diminished.

This analysis summarizes the unfavorable conditions for the development of Hakka language and culture, which alerted the Hakka to the crisis that their ethnic consciousness was vulnerable to collapse. Thus, the awakening movement of Hakka consciousness occurred.

At the end of the eighties, the people’s cry for the dissolution of all the disreputable institutions remaining from the Martial Law period, including a return to the mother tongue movement, the establishment of democratic and just political and economic systems, and the striving for the legitimate rights of the Hakka, aiming at a sound ethnic relationship and social order, has been heeded To move towards an open and pluralistic society with understanding, harmony and respect among different ethnic groups.

We can see that the cultural characteristics of the Hakka differ from the Hoklo in all respects, including architecture, music, food, religious beliefs, customs, and gender roles in the family. It is particularly remarkable that in the traditional Hakka concept of family, the male gender pursues success in academic honors and official employment while the female takes charge and runs the household, and furthermore, maintains the ideal family tradition of study and farming.

Hakka women were expected to manage “three fore ends and three hind ends” in regard to their work: “stove in front and pan in back” for cooking, “needle in front and thread in back” for sewing, and “the field in front and the ground in the back.” For cultivation on hills or fields, since Hakka women usually worked in the fields, there was no common practice of foot-binding like Hoklo, and thus people were impressed that Hakka women worked hard but never complained, and could bear the pressure of work and hardship. On the other hand, the Hakka have a highly regarded tradition of learning and literature.

An essay by critic P’eng Jui-chin summarizes the distinctive features of the works of Hakka writers in three points: (1) a solid ethnic spirit reflected in the literary activities of Hakka writers, (2) an interpretation of life in terms of the relationship between man and the earth, (3) the emergence of Hakka women, who are characterized by strong personalities.

However, in contemporary Taiwan society, it is becoming more and more common for the Hakka ethnic group to coexist and interact with other groups, and under no circumstances can they separate themselves from the outside world; Thus it is difficult to preserve any purely Hakka cultural characteristics, and even more difficult to expect Hakka literature to have unique characteristics. However, as long as these writings reflect the life of the Hakka people and naturally preserve their habits, customs, religion, and language characteristics, they are recognized as Hakka literature.

Du Pan Fang-ge

The poetess who crossed languages and cultures

Perhaps when I start with the poems of Du Pan Fang-ge (March 9, 1927 – March 10, 2016), I see her as a vivid embodiment of contemporary Taiwan history. She is a poetess who crossed languages and cultures, as she expressed the political oppression and social identity struggles of the Hakka people under Japanese colonial rule in her literary works written in Japanese, Mandarin (Chinese), and Hakka.

After overcoming language barriers in writing, Du created a rational and sophisticated style of Taiwanese poets, which qualified her to win the Hakka Literary Achievement Award in 2007 for her important role in the development of poetry in Taiwan.

Du was born into a prestigious Hakka family in Xinpu (Hsinchu County, northern Taiwan), to grow up aware of the many difficulties and dilemmas Taiwanese face. Starting with her father being oppressed in his work by the Japanese colonial government; Also while studying at the Japanese elementary school in Taiwan, where Du was also bullied by her Japanese peers, her childhood experience shaped her understanding of colonial society and influenced her later writing.

Upon entering Hsinchu National Girls’ High School, Dou began writing poetry, novel, and prose in Japanese as a means of escaping reality. In poetry, Du expressed the suffering of all Taiwanese society, as well as the personal tragedy she went through as a writer representing her generation. “The Multilingual Generation”.

Later, Du attended a two-year girls’ high school in Taipei where she learned to be an obedient housewife, studying traditional female skills such as sewing and flower arranging. The “traditional virtues” she received at school belied her self-identity as a poet, and forced her to focus on family life before continuing to write poems.

After the end of World War II, and the surrender of Japan, the island of Taiwan was placed under the rule of the Republic of China on the twenty-fifth of October 1945, when Du to begin learning the Chinese language and to return to the poetic scene in Taiwan by joining the (Lee) Poetry Association in 1965. Encouraged by member’s literary society and began publishing poems in Chinese.

Since the 1980s, Du has also been actively involved in writing Hakka poems to promote the indigenous immigrants. She believed that poetry is shaped by an individual’s feeling and knowledge about the natural order and reality, and thus her writing style focuses on inner thoughts and feelings rather than the form and technique to brilliantly present her thoughts and imagination about the world.

Tseng Kuei-Hai

A doctor treats the history of his country with poetry

Tseng Kuei-Hai (1946-), Taiwanese poet and physician. Beginning in 1973, as a pulmonologist, Tseng Kuei-Hai carries a stethoscope in one hand and a pen in the other: the stethoscope for his patients and the pen for his land. In poetry, Tseng expresses his longing for his homeland, and outside of the poem, he proposes and participates in public affairs, Taiwanese politics, and social reforms.

In 1982, the poet founded the literary magazine Literary Taiwan with other writers.

For three decades, poet Tseng Kuei-Hai devoted his life to social movements; but at the same time, he maintained his literary production, so he issued 23 books, so far, including 19 poetry collections. With his pen, Tseng stands for the land and the people and talks about the mission of Taiwanese writers throughout the history of colonialism in Taiwan. He believes that “the true voice of literature should represent an echo of the earth’s suffering, compassion, fate, people’s feelings and hopes.”

At a ceremony honoring Tseng, Taiwan Culture Minister said that Tseng is not only a Hakka poet, but also a Taiwanese writer, and most importantly, that Tseng is the pride of Taiwan, he is devoted to everything related to his homeland and has Setting a milestone for Taiwanese literature.

Wu Ching-Fa

The movement of the organic intellectual

Wu Ching-Fa is a novelist, poet, prose writer and literary reviewer. Born in Milnong, Kaohsiung, Taiwan (September 14, 1954), Received a Bachelor’s degree in Sociology. He was an editorial writer for the daily newspaper Taiwan Daily and also hosted a radio talk show.

Wu’s writing often explores ethnic conflict in Taiwan from the perspective of young people. His books include Street of Weeping Swamps (1985), Autumn Chrysanthemums (1988), Spring and Autumn Tea House (1988), and The Boyhood Trilogy (2005). His Autumn Chrysanthemum became the basis for the film Youth without Regrets.

As vice president of the Council on Cultural Affairs (CCA), Wu has also been involved in international cultural outreach. He worked to keep a historic clinic from demolition, and founded Culture.tw, an English-language web portal funded by the Council for Cultural Affairs and run by the Central News Agency.

In 2017, Wu worked with the Ministry of Culture to display letters written by political prisoners during the White Terror at the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Pingtung County.

Chiang Fang-tzu

Books are a forest; I read all its trees

Fang-Tzu Chang was born in 1964, to later immerse herself in the world of Hakka literature, beginning with her participation with local women writers in the founding of the Taiwan Association for Hakka Women’s Literature, and her tireless and long-term activity in various Hakka cultural events, strengthening the status of that literature quality in her country.

Her career has her having books, photo albums, and collections of poetry to read, and she’s fully activated stray mode. Before the second collection of poems was published, literary friends founded the Female Whale Poetry Club, and in those few years, feminist and sexuality books began to appear on the shelves again. Movies were another type of reading for her, and sometimes she took time off to find a corner in the movie library to catch up. During this period, Woolf entered the nocturnal reading time.

__________________

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is a renowned poet, novelist, journalist, travelogue writer of Egypt. He is author of over three dozen books and Editor-in-Chief, Silk Road Literature Series.

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is a renowned poet, novelist, journalist, travelogue writer of Egypt. He is author of over three dozen books and Editor-in-Chief, Silk Road Literature Series.