When America sneezes, developing Asian economies suffer from pneumonia….

By Nazarul Islam

I was sharing my notes with Bangladeshi Economist Tanvir A. Khan, PhD, whose friendship I have enjoyed for nearly six decades. He was concerned about the rising prices of essentials in the Asian countries, particularly in Bangladesh.

Dr. Khan came up with his informed opinion: The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.

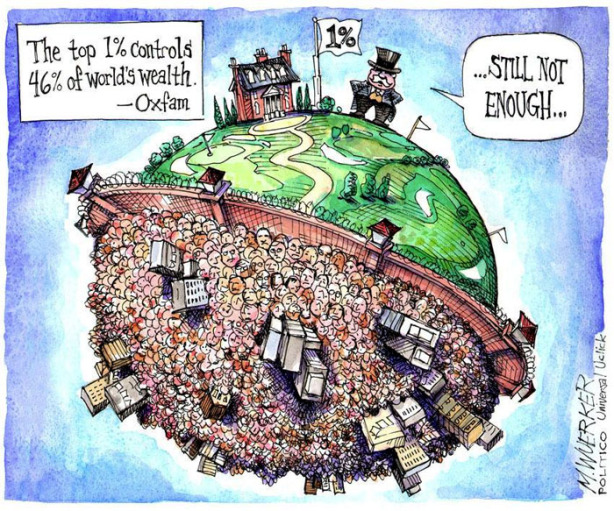

Our entire system, in an economic sense, is based on restriction. Scarcity and inefficiency are the movers of money; the more there is of any resource the less you can charge for it. The more problems there are, the more opportunities there are to make money.

On the other hand, myself, a non-Economist had to share my own information—based on my compulsive reading habit.

This reality is a social disease, for people can actually gain off the misery of others and the destruction of the environment. Efficiency, abundance and sustainability are enemies of our economic structure, for they are inverse to the mechanics required to perpetuate consumption.

This is profoundly critical to understand, for once you put this together you begin to see that the one billion people currently starving on this planet, the endless slums of the poor and all the horrors of a culture due to poverty and pravity are not natural phenomenon due to some natural human order or lack of earthly resources. They are products of the creation, perpetuation and preservation of artificial scarcity and inefficiency.

Both agreed to look around what is happening in the US. Because, when America sneezes, developing Asian economies suffer from pneumonia….

Welcome to the shortage economy. After four decades of production and consumption—we have arrived at a point where optimized and increasingly global supply chains made goods available at rock-bottom prices; where even scarce energy suddenly became cheap and abundant because of new drilling technologies.

Today, America has suddenly run smack into scarcities for everything from lumber to copper, computer chips to rental cars, truckers to restaurant workers, ammunition for guns to chlorine tablets for swimming pools.

Americans are expecting more such shortages and price increases, economists say, as eager-to-spend consumers contemplate a post-pandemic economy and as record government stimulus boosts demand. And the silver lining in this is that most of these shortages are expected to be temporary.

“It’s going to seem a whole lot worse than it might about a year from now,” says Gary Schlossberg, global strategist for Wells Fargo Investment Institute. There’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

Looming over this burst of scarcity is the fear that the United States will return to the high inflation of the 1970s – a fear that many economists tend to discount.

“There is an issue that you have deja vu all over again, which could happen because of the policy mistakes of the type that were made in the 1970s,” says Frederic Mishkin, professor of banking at Columbia University and a former member of the Federal Reserve’s board of governors.

However…..this time, he says, “the level of mistakes made in the 1970s is extremely unlikely.”

An employee manually assembles a circuit-board element before a ribbon-cutting ceremony to mark the opening of a Nanotronics manufacturing center at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in the Brooklyn borough of New York on April 28, 2021. Growth in U.S. manufacturing slowed slightly in April, reflecting in part supply-chain troubles, after hitting a 37-year high in March.

The supply of certain computer chips is so constrained right now that car companies have had to reduce their own production – or not install certain features, such as navigation systems, which used to come standard in models. These shortages ripple out to create new shortages.

Unable to buy new vehicles, rental car companies are now short of cars and charging sometimes double the price of a year ago. The chip shortage is now spreading to other industries, such as washing machines and smartphones. In March, a Samsung executive warned that the company might have to skip the rollout of a new Galaxy Note smartphone.

Even when the pandemic didn’t cause the shortage, high demand is creating bottlenecks. Ammunition-makers were cutting back after Hillary Clinton unexpectedly lost the 2016 presidential election. (The election of Democratic presidents has typically boosted gun sales.)

When many Americans bought a gun in 2020 – a surge that accompanied the pandemic and civil rights protests after the murder of George Floyd – ammunition manufacturers were caught flat-footed, says Mr. Oliva. Ditto for the container ship industry, which was downsizing before the pandemic, and now has a serious capacity shortage as exports boom.

Another bottleneck is a decades-old shortage of truck drivers. The problem is magnified when goods are in such big demand. But the problem isn’t really the supply of potential drivers, but the extremely poor pay for long-haul work, says Michael Belzer, a former truck driver and now professor of economics at Wayne State University.

Adjusting for inflation, “we’re probably at about 50% on average today of the overall annual compensation of where we were back then [in the 1970s]. So it shouldn’t be a big shock that we have a hard time getting drivers.”

Typically, the market would force wages up. But deregulation in the 1970s and the decline of unions have meant that drivers who work as independent contractors haven’t had the market power to push for higher pay at the trucking companies that rely on them. Instead, the industry sees extremely high turnover.

A shortage of service workers is forcing some large retail and restaurant chains to raise wages to attract them back. Many workers are hesitant to go back, either because of fear of exposure to the coronavirus or continued school closures, which make it difficult for parents without childcare to reenter the workplace.

_____________________

About the Author

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his 119 articles.

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his 119 articles.