In the U.S. today, two-thirds of white Christians practice a “religion of whiteness,” a new study finds.

BY MICHAEL O. EMERSON

My colleagues and I have done extensive research on race and religion for 30 years. We’re now wrapping up an intensive, three-year national research project where we heard from thousands of Christians and examined trends in church attendance and commitment. We have a clear conclusion: God is shaking down the U.S. church. It is currently in a reckoning, the likes of which has not been seen for centuries.

As our team interviewed Christians of color across the U.S., we heard a similar and painful story repeated: White Christians, by their actions, seem to favor being white over being Christian. Christians of color cited many instances of that type of behavior, national and local, communal and personal. We wondered if this was the case empirically and, if so, why. As we tested the hypothesis, we found a plethora of evidence substantiating what we heard.

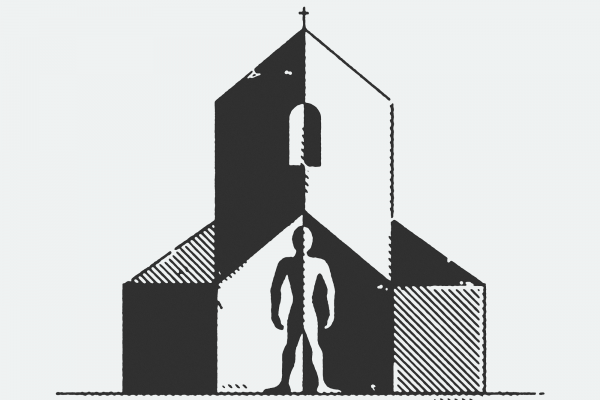

My co-author Glenn Bracey and I are proposing a theory in our forthcoming book, The Grand Betrayal: Most church-attending white Christians are not bad Christians. This is because they are not Christian at all. Instead, we propose they are faithful followers of a different religion: the “religion of whiteness.”

In the U.S. today, an entire religion has developed around the worship of the dominance, centrality, privilege, and assumed universality of being white. “White is right,” so this religion postulates, and it has developed a particular set of beliefs, practices (such as a highly selective use of biblical scriptures), and organizations to support, defend, and teach its “faith.”

We can make predictions based on the theory and test them empirically. Let me offer one example. We selected three Bible verses that speak about empowering minority ethnic groups (Acts 6:1-7), welcoming foreigners (Deuteronomy 24:14), and confessing the sins of your own group (Nehemiah 1:6). We asked those who told us they believe the Bible should always be used to determine right and wrong if they agreed with the verses and analyzed their responses by racial group. For African American and Hispanic Christians, the majority strongly agreed with the verses. But for white church-attenders, only one-third strongly agreed. These white churchgoers differed from other Christians in that the majority took issue with the Bible.

We went further by including a fourth verse as a control, one that referred only to individual piety: the injunction not to use unwholesome words (Ephesians 4:29). Here all groups—no matter their racial category—strongly agreed with the Bible verse imploring Christians not to use unwholesome words. White practicing Christians agreed with the Bible exactly as other Christians when the verse did not ask about showing favor to groups other than their own.

We found this pattern over and over again: White practicing Christians differed from Christians of other racial groups and from non-Christian whites whenever the topic was race. For example, white practicing Christians are twice as likely as other whites to say “being white” is important to them and twice as likely as other whites to say they feel the need to defend their race. Through extensive statistical analyses, we found that two-thirds of practicing white Christians are following, in effect, a religion of whiteness. They repeatedly placed being white ahead of being Christian; the findings were not explained away by political affiliation, location, age, education, income, gender, or other factors.

So, where do we go from here? In this time of reckoning, our churches are being sifted. The middle ground is ending. Social justice movements are a key part of this reckoning. Quite simply, Christian justice movements centered on bringing the love of Christ to all people are invigorating U.S. Christianity and have the immense possibility to do more so in the future, for at least three reasons. First, these movements are largely multiracial, and often BIPOC-led. This is essential—a demonstration and enactment of what must come to be. Second, these movements draw people out of a focus on one’s self and one’s own group and instead direct Christians to the biblical essence of focusing on God’s reign and creation. And third, these movements bring to light where various churches stand. We need the practitioners of Christianity to pray and work for mass conversions from the “religion of whiteness” to an authentic Christianity rooted in the radical teachings of Jesus.

It is both a difficult and an incredibly invigorating time. The church will not look the same when we get to the other side.

___________________

Michael O. Emerson is a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and co-author of the forthcoming The Grand Betrayal: The Agonizing Story of Race, Religion, and Rejection in American Life.

Michael O. Emerson is a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and co-author of the forthcoming The Grand Betrayal: The Agonizing Story of Race, Religion, and Rejection in American Life.

Courtesy: Sojourners