The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse.

Julien Levesque

[The study of Sindhi nationalism has remained over-determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state. The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. As a result, it has mainly received attention when sudden outbursts of violence seemed to threaten the stability of the state. However, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails. Rather than address questions of failure or success, this article shows that the construction of a nationalist “idea of Sindh” has been a continuous process throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It also illustrates how an aspirational middle-class played a central role in this process. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse. This process translated into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributed to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.]

Introduction

In the aftermath of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto’s assassination on December 27, 2007, thousands of angry protesters took to the streets in Pakistan, destroying and burning cars, trucks, trains, buses, government offices, police stations, and other state symbols. This rage was most potent in the southern Sindh province, where disturbances lasted for several days, fueled by the slogan “Na khape, na khape, Pakistan na khape!” (We don’t want/need Pakistan). By chanting in this way their separatist temptations, many Sindhis expressed the feeling of being directly targeted by the killing of the woman they affectionately called “Bibi” (sister) or “Sindh Rani” (the queen of Sindh). To them, almost thirty years after the execution of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the state of Pakistan was once more responsible for the death of a Sindhi political leader. It took Benazir Bhutto’s widower Asif Ali Zardari’s intervention for the public show of anger to subdue. He urged demonstrators to set aside their call for independence by reversing their slogan and declaring: “Pakistan khape.”

The tension following Bhutto’s assassination is indicative of the uneasy relationship that many Sindhis have expressed vis-à-vis the state of Pakistan since independence in 1947. However, observers generally dismiss the political implications of resentment among Sindhis by pointing Sindhi nationalist parties’ poor showings in elections and their incapacity to build a mass movement, let alone obtain independence. For this reason, Sindhi nationalism is often described as a political failure. As a result, it has received little attention from journalists and scholars alike, who seem only to take interest when sudden outbursts of violence threaten the stability of the state. Indeed, most studies on Sindhi identity politics focus on the 1980s, when an anti-state uprising provoked harsh military repression, and ethnic conflict deepened the rift between various groups living in Sindh. In the main narrative of Pakistan’s political history, debates on Sindhi identity and the related question of the level of political power Sindhis should exert in Pakistan appear as little but a sub-plot. Instead, civil-military tensions and the contested place of Islam in the state occupy the main stage. Matters of inter-province conflict tend to be seen from the vantage point of Pakistan’s federalism and the state’s difficulty in dealing with “centrifugal forces.” When Sindhi nationalism receives a mention, its study remains over determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state – thus overlooking the actions and the discourse of nationalist groups. The question of identity construction has been examined among Diasporic Sindhis and Sindhis in India. However, there still lacks a detailed study of Sindhi identity construction in Pakistan. Indeed, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails.

This article partially fills this gap by taking a Sindhi-centric lens to propose a narrative of the birth and evolution of Sindhi nationalism throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It dovetails into current endeavors that seek to displace the somewhat dominant depiction of Pakistan as a state in constant crisis. Such scholarship reexamines Pakistan’s political history in a way that gives more significant space to groups that have not necessarily held state power, such as oppositional and left movements. Defining Sindhi nationalism in a narrow sense as a radical anti-Pakistan movement poses a problem because it inevitably raises the question of its political success or failure. This article eschews Sindhi nationalism’s capacity to obtain independence and instead redirects the focus on socio-political dynamics in Sindh and group cohesion, boundaries, and identity markers – in short, what Sindhi nationalism does. Moreover, moving beyond the question of the success or failure of Sindhi nationalism allows us to raise the question of its broader contributions to Pakistan’s political life and the process of nation-building in Pakistan. One can approach Sindhi nationalism as a discourse (asserting Sindh’s existence as a nation) or a movement (comprising promoters of the nationalist discourse). One can also approach it as a social process through which the nationalist understanding of group boundaries spreads and transforms society. This article attempts to link all three dimensions through a socio-historical account of Sindhi nationalism. Indeed, relegating the question of success or failure helps us see Sindhi nationalism as a continuous process, rather than through isolated moments or sporadic outbursts when it stepped onto the main stage of Pakistani politics.

Therefore, this article follows two aims. First, I examine the progressive and continuous elaboration of the Sindhi nationalist discourse through the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. I highlight the role of three distinct generations of Sindhi men and (in a much smaller number) women in conceptualizing and spreading Sindhi nationalism. While the three generations share certain features in their members’ trajectories, each of them experiences a different historical context and brings its specific contribution to Sindhi nationalism. The second part of this article raises the broader contribution of Sindhi nationalism to Pakistan’s politics. I investigate two aspects: how Sindhi nationalism translated institutionally in cultural policy; and how Sindhi nationalism participated in party politics. I conclude by suggesting that scholars examine Sindhi nationalism in its co-constructive relation with the Pakistani state’s conception of nationhood.

Therefore, this article follows two aims. First, I examine the progressive and continuous elaboration of the Sindhi nationalist discourse through the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. I highlight the role of three distinct generations of Sindhi men and (in a much smaller number) women in conceptualizing and spreading Sindhi nationalism. While the three generations share certain features in their members’ trajectories, each of them experiences a different historical context and brings its specific contribution to Sindhi nationalism. The second part of this article raises the broader contribution of Sindhi nationalism to Pakistan’s politics. I investigate two aspects: how Sindhi nationalism translated institutionally in cultural policy; and how Sindhi nationalism participated in party politics. I conclude by suggesting that scholars examine Sindhi nationalism in its co-constructive relation with the Pakistani state’s conception of nationhood.

The Social Construction of the Idea of Sindh

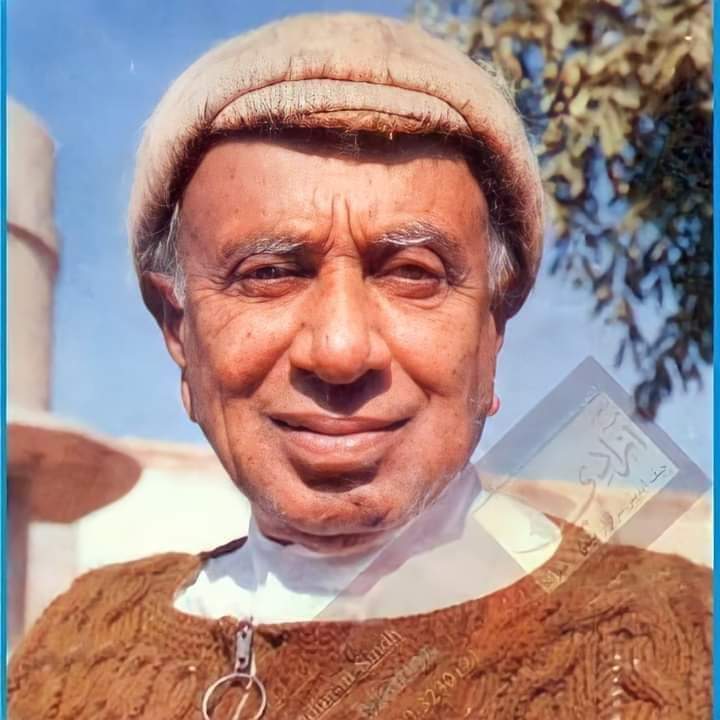

Moving away from the question of the success or failure of Sindhi nationalism helps us refocus on what nationalism does to shape and re-shape group boundaries. It invites us to concentrate on the way nationalist entrepreneurs seek to impose their understanding of the social world, or what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu named their “di-vision” of the social world.9 What is the Sindhi nationalist “di-vision” of the world, and how was it constructed? I suggest that the Sindhi nationalist discourse rests on an ethnic understanding of Sindh as a historical and socio-cultural unit that warrants autonomous political power. This “idea of Sindh” assumes cultural continuity since the Indus Valley civilization and essentializes Sindhi culture as defined by a set of symbols. These symbols include Sufi Islam and Sufi Saints (with a particular reference to Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai), language, “folk” culture and crafts, ajrak and topi, and selected historical figures. This article does not focus on the idea of Sindh itself but examines how it was crafted over time and by whom. Looking at the social moorings of the idea of Sindh indicates that its originators and proponents primarily belonged to the aspirational middle-class. This section first briefly traces the biography of the founding father and leading ideologue of Sindhi nationalism, G.M. Sayed (1904–1995). It then follows a three-generational narrative of the construction the idea of Sindh, a process marked by collective mobilizations and informed by the social and political transformations affecting the region. (Continues)

____________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence.

Courtesy: Brill

( Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)