A specialist in the studies of slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and women’s history, Cook-Bell tells in her book the compelling stories of enslaved women and the ways in which they fled or attempted to flee bondage during and after the Revolutionary War.

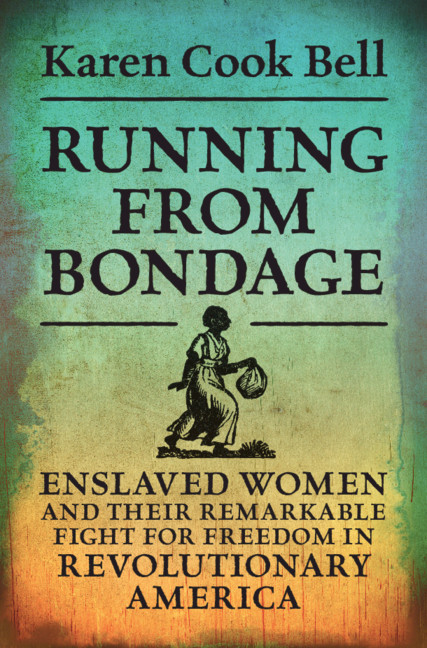

On March 5, 1770, a twenty-three-year-old woman, her eight-month-old daughter, and her husband escaped from bondage in Leacock Township in Pennsylvania. This unnamed fugitive woman was not the only one who tried to escape from slavery; one-third of all runaways during the Revolutionary Era were women and girls. Despite this number, the stories of these enslaved and fugitive women and the contributions they made to the cause of liberty have rarely been told. In her new book ‘Running from Bondage: Enslaved Women and Their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America’ (Cambridge University Press; July 1, 2021), historian Karen Cook-Bell aims to rectify this historical omission. A specialist in the studies of slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and women’s history, Cook-Bell tells the compelling stories of enslaved women and the ways in which they fled or attempted to flee bondage during and after the Revolutionary War. “Enslaved women ran away,” Cook-Bell explains. “Women in bondage were not content, and running away, or flight, was one of the ways in which they registered their protest.” Robert Greene II, Senior Editor of ‘Black Perspectives interviewed Cook-Bell about her newest work.

Robert Greene II (RG): What inspired you to write Running from Bondage?

Karen Cook-Bell (KCB): Researching my first book introduced me to women who fled slavery either alone or with their families during the late eighteenth century. This led me to question how widespread was the flight of enslaved women. My research led me to the American Revolution which according to historian Benjamin Quarles was the first large-scale slave rebellion. I wanted to tell the stories of these women who fled or attempted to flee bondage during the Revolutionary Era.

Running from Bondage tells the story of enslaved women who escaped bondage during the era of the American Revolution, a time period when the chaos of war and lack of oversight made escape possible for Black women in both the North and South. One-third of fugitives were in fact enslaved women.

The book consists of five chapters that examine why and how enslaved women escaped bondage and the challenging circumstances they faced over the course of five decades from 1770 to the 1810s. I provide an overview of enslaved women’s labor during the colonial period and their various resistance strategies and then take a deep dive into looking at the lives of individual women who escaped. The book really underscores the fact that enslaved women were not one-dimensional figures but lived multi-dimensional lives as wives, mothers, sisters, and freedom fighters.

The book consists of five chapters that examine why and how enslaved women escaped bondage and the challenging circumstances they faced over the course of five decades from 1770 to the 1810s. I provide an overview of enslaved women’s labor during the colonial period and their various resistance strategies and then take a deep dive into looking at the lives of individual women who escaped. The book really underscores the fact that enslaved women were not one-dimensional figures but lived multi-dimensional lives as wives, mothers, sisters, and freedom fighters.

RG: How did you research the book, and did you learn anything that especially surprised you?

KCB: I began this study several years ago and the research for the study brought me to the realization that there is so much that historians can uncover in the lives of enslaved women. Although the evidence is fragmented, the experiences of fugitive women are far from unknowable. I examined over 1,000 runaway newspaper advertisements from the eighteenth century. There is a great amount of literature on enslaved people who escaped during the 1800s however the accounts of runaways during the 1700s are limited to colonial newspaper advertisements for runaways.

Other sources include a published interview with George Washington’s escaped slave Ona Judge and trial records of fugitive slaves.

The story of Margaret Grant will surprise people. Margaret escaped slavery twice, first in 1770 and then in 1773, both times from Baltimore, Maryland; and in her first escape, she wore men’s clothing and sought to conceal her identity by dressing as a waiting boy to an escaped English convict servant, John Chambers. So Margaret sought to escape by passing as both white and male performing fugitivity in a way that Ellen Craft, another escaped slave, would do decades later.

Also surprising is the fact that women not only ran away with immediate family members but also in groups without established kinship relations. They correctly perceived that their best chances for freedom resided with a British victory and a disruption of the existing social order. In the north and south, women fled to urban centers, took refuge in British camps, aided the Loyalist cause as spies, cooks, nurses, and performed duties for the British Army Ordnance Corps. In the postwar period, most Black women did not seek freedom in the North but instead pursued “informal freedoms” in urban cities such as Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans where they defined freedom in terms of family and mobility. In these cities, they relied on networks of acquaintances, marketable skills, clothing, and language skills to assume identities as free women and carve out free spaces for themselves.

RG: What impact do you see the Revolutionary War having on enslaved women?

KCB: The war bolstered the independence of fugitive Black women, gave them increased access to their families with whom they fled, and greater autonomy in their day-to-day lives once they reached safe-havens. Women ran away during the Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary period to claim their liberty, an act which they viewed as consistent with the ideals enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. Underlying the causes of their flight were efforts to defend their bodies and womanhood against exploitation, as well as to protect their children from the deleterious effects of the institution of slavery.

To understand women’s lives in, and resistance to, slavery requires examining their efforts to escape bondage, and symbolically how what they wore and carried with them in the process of fleeing were political acts that challenged enslavers’ powers. Political acts of resistance, such as flight, and women’s thoughts about resistance are in constant dialogue. Although the flight of enslaved women was one of institutional invisibility in that there was no formal organization, no leaders, no manifestoes, and no name, their escape constituted a revolutionary social movement in which fugitive women made their political presence felt. In fact, fugitive women displayed a radical consciousness that challenged the prevailing belief that enslaved women could not gain their freedom through subversive actions.

RG: What do you see as these women’s legacy today?

KCB: Instead of viewing Black women as at the margins of the American Revolution and abolitionism, it is important to see them as visible participants and self-determined figures who put their lives on the line for freedom. They protested with their feet by running away which underscores the vital role of Black women in seeking to move the nation toward a more perfect union.

This story represents an important part of Black women’s political history and adds to the discourse of how African American women organized in their communities, protested slavery and segregation, built institutions, and fought for equal access to the ballot. Black women have been at the forefront of movements to address iniquity, social oppression, and freedom for the Black community for centuries. The activism of Stacy Abrams, for example, and her work to address voter suppression are representative of the ways in which Black women continue to shape and perfect America’s democracy. This is a fight that began during the Revolutionary Era.

RG: What are you working on now?

KCB: I am editing a book on African American women during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era which is being published by Cambridge University Press. The book explores the ways in which Black women, from diverse regions of the American South, employed various forms of resistance and survival strategies to navigate one of the most tumultuous times in American history. It is a collection of case studies of Black women’s lived experiences in the Confederate South and border regions of the U.S. which highlights the complexity of Black women’s wartime and postwar experiences and provides important insight into the contested spaces they occupied.

___________________

Courtesy: Black Perspectives (The award-winning blog of the African American Intellectual History Society -AAIHS) and History News Network