I read a woman’s name, Kushalibai, appearing in 1895, 1902, 1905, 1908, 1915 and 1918. While she accompanied family members on their visits, there is no record of her visiting Haridwar with her husband or her son Chandiram

Saaz Aggarwal

I first saw these ledgers in Haridwar in 2015, while working on the family history of a Sindhi family. The oldest entry for their surname was dated 1824 – before the railways came to Sindh. Journeys each way would have taken weeks, and been by boat, camel and bullock cart.

The records are signed accounts of travelers to Haridwar, their names and the names of their male children, male siblings, male uncles, and male ancestors. Most often they came to perform the final rites of a close family member; sometimes it was a halt on a pilgrimage further into the mountains.

I was intrigued to read a woman’s name, Kushalibai, appearing in 1895, 1902, 1905, 1908, 1915 and 1918. While she accompanied family members on their visits, there is no record of her visiting Haridwar with her husband or her son Chandiram. What made Khushalibai such a ‘rolu’ – someone who revels in travel and adventure – at a time when it was unusual for a woman to wander so far so often? It seems that she was well off and well cared for; and not particularly bound by domestic duties. When she died, in 1919, it was a grand-nephew who performed the final rituals in Haridwar and not Chandiram. Perhaps Khushalibai was a widow; perhaps her son died young; perhaps they were disabled – who will ever know? Or perhaps it was just the Sindhworki lifestyle – where men went to work in distant lands, visiting their families for only a few months every 2 or 3 years – that was responsible for the extended separation.

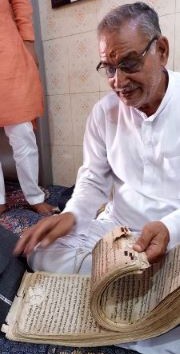

The paper of this ledger is so delicate that it crumbles as the pages are turned, and he is reluctant to turn each page to look for the information we have come for. When we suggest that he digitize it, he speaks of intellectual property and privacy, and explains that he would never allow that to happen as he cannot give away something so precious that his family has been instrumental in recording and preserving for centuries.

Rather than individual hand-written entries, this ledger contains information recorded by Pandit Anirudh’s ancestor with names and addresses of the visiting pilgrims as well as their family members. While these are only names of male family members, today Pandit Anirudh is meticulous about noting female names as well when updating family records.

________________

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwal | Black-And-White-Fountain

[…] Also read: Haridwar – Records of Sindhi Pilgrims’ Travel and Worship […]