In the 1400s, approximately 700 Memon families from Thatta chose to migrate to Kutch and subsequently to Kathiawar, seeking religious openness and new business prospects

By Bakhtyaar Shahzad

Step into the vibrant linguistic landscape of Sindh, and you’ll discover the fascinating language of Memoni, spoken approximately by 2 million individuals worldwide who identify themselves as Kathiawari Memons yet it is highly intelligible with Sindhi. As we delve into the historical tapestry of this community, we witness their unique journey marked by migration and cultural assimilation, acculturation and homecoming, all while retaining their roots in Sindh!

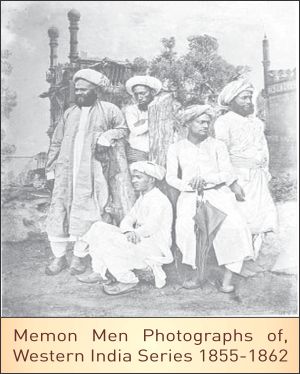

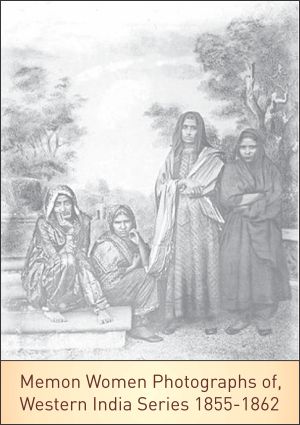

To understand the origins of Memoni, we must trace back to the region of the historical city of Thatta in Southern Sindh, also known as Laar. In ancient times, this land was inhabited by Lohana Hindus, a prosperous mercantile community. Meanwhile, the neighboring state of Gujarat emerged as a bustling hub of trade, boasting an impressive array of various sea ports along the Arabian Sea coast connecting the Middle-east with the Indian Subcontinent. It was in this dynamic environment, with commercial links stretching from Karachi to Surat that Lohanas thrived in business, encompassing the Kutch and Kathiawar regions.

During the 7th to 13th centuries, Sindh experienced profound political and ideological changes, resulting in instability and power struggles among various ethnic and religious groups. Buddhism initially held sway, but it was temporarily overshadowed by Hinduism during the Chach dynasty’s rule as the state religion, although its widespread practice was limited. The Arab invasion prompted a gradual assimilation of many Buddhists into Hinduism, while the introduction of Islam was facilitated by Muslim missionaries and the government’s policy of taxing non-Muslims. However, it was in the 12th and 13th centuries that a significant religious transformation occurred, marked by mass conversions to Islam through the dedicated efforts of missionaries. These missionaries, deeply immersed in Sindhi culture, presented the principles and theology of Islam in local languages, building trust among the Hindu population. Their rhetorical skills and understanding of societal conditions played a crucial role in the remarkable shift towards Islam, particularly influencing the Lohanas of Southern Sindh, who had strong roots in Hinduism.

After the partition of India in 1947, Memons re-migrated to Sindh; their ancestral homeland, which they had left no more than six centuries ago

Meanwhile, Buddhist missionaries faced opposition due to their vocal criticism of the Brahmin hierarchy and the caste system within Hinduism. In contrast, Muslim preachers adopted a different approach. Instead of directly challenging Hindu sentiments, they communicated the principles of Islam using vernacular languages, thereby establishing rapport with the Hindu population, which had been somewhat not effectively done by the Buddhists who had more of become rebels against the Hindu tradition. The ruling position of Muslims also appealed to the locals, as conversion to Islam offered socio-economic advantages such as employment opportunities and privileges within government institutions. While forced conversions did occur, their impact on overall numbers was limited. These factors, coupled with effective persuasion, incentivized conversions and expanded the influence of Islam beyond religious realms.

The homecoming was not without its challenges. In what they perceived as a foreign land, they encountered a sense of alienation from the Sindhi population, who regarded them as outsiders

Among the converts, the Lohanas of Southern Sindh, who had staunchly adhered to Hinduism, were particularly influenced by the persuasive Islamic preachers. The missionaries’ skillful rhetoric and comprehension of societal conditions enabled them to navigate the religious landscape successfully, leading to a notable shift towards Islam in Sindh among the Lohana community. As most Muslim missionaries were traders themselves, Lohanas had frequent contact with them. Consequently, some Lohanas converted to Sunni Qadriya Sufi Islam, becoming known as “Momins” or believers, a term that later morphed into “Memons.” Others embraced Ismaili Shia Islam and were referred to as Khwajas or Khojas. ‘Thus, the Memons and Khojas underwent a transformation from Hinduism to Islam under the guidance of Ismaili and Sunni Pirs.’ (Pirbhai, Reza – 2009). This transformative period not only witnessed religious conversions but also cultural and linguistic developments, exemplified by the production of literature in Sindhi, including poetry, documents, chronicles, and treatises but mainly the emergence of new ethnic identities under the umbrella of Sindhis.

While officially considered a dialect of Sindhi, Memoni is unfortunately giving way to Urdu among the younger generation

While officially considered a dialect of Sindhi, Memoni is unfortunately giving way to Urdu among the younger generation

After the partition of India in 1947, Memons re-migrated to Sindh; their ancestral homeland, which they had left no more than six centuries ago. They arrived with a newfound identity and nationality, deeply influenced by the vibrant Gujarati culture that had become their home and were also semi-fluent in Urdu with a recognizable accent. However, this homecoming was not without its challenges. In what they perceived as a foreign land, they encountered a sense of alienation from the Sindhi population, who regarded them as outsiders. Despite the gradual erosion of Sindhi cultural elements within the Memon community, there is one significant aspect that perseveres—the Memoni language. While officially considered a dialect of Sindhi, Memoni is unfortunately giving way to Urdu among the younger generation. Yet, amidst this linguistic shift, in cities like Hyderabad, it is not uncommon to find Memon businessmen engaging effortlessly in Sindhi conversations with their customers. Some have even mastered the intricate pronunciation of Sindhi implosives which reflects as to how the Memons have felt homely and connected to Sindhi language.

In cities like Hyderabad, it is not uncommon to find Memon businessmen engaging effortlessly in Sindhi conversations with their customers

Within Pakistan, particularly in Karachi and Hyderabad, Memon settlements have organized themselves into jamaats, fostering networks and social connections to support their commerce and enhance their overall quality of life. These jamaats, such as Surat Memon Jamaat, Godhra Memon Jamaat, Bhavnagar Memon Jamaat etc, have played a vital role in preserving Memon cultural identity. However, the identity crisis and turmoil between Sindhis and Mahajirs in Karachi led many Memon leaders to become politically involved, aligning themselves primarily with the Urdu-speaking community and distancing themselves from Memoni language. Economic factors also influenced the adoption of Urdu, as many of their employers and business partners belonged to the Urdu-speaking community. These factors contributed to the formation of a distinct Memon identity, politically influenced by Urdu nationalists, often carrying negative sentiments towards Sindhis and a sense of separation from the mainstream Sindhi community. Although the previous generation held onto their Sindhi heritage, it is gradually fading among the younger generation.

Within Pakistan, particularly in Karachi and Hyderabad, Memon settlements have organized themselves into jamaats, fostering networks and social connections to support their commerce and enhance their overall quality of life. These jamaats, such as Surat Memon Jamaat, Godhra Memon Jamaat, Bhavnagar Memon Jamaat etc, have played a vital role in preserving Memon cultural identity. However, the identity crisis and turmoil between Sindhis and Mahajirs in Karachi led many Memon leaders to become politically involved, aligning themselves primarily with the Urdu-speaking community and distancing themselves from Memoni language. Economic factors also influenced the adoption of Urdu, as many of their employers and business partners belonged to the Urdu-speaking community. These factors contributed to the formation of a distinct Memon identity, politically influenced by Urdu nationalists, often carrying negative sentiments towards Sindhis and a sense of separation from the mainstream Sindhi community. Although the previous generation held onto their Sindhi heritage, it is gradually fading among the younger generation.

The journey of the Memons reflects the intricate interplay between culture, religion, and language. It embodies the evolution of a community that has traversed geographical boundaries, navigated religious transitions, and strived to preserve its unique linguistic heritage in an ever-changing world. The story of Memoni and its connection to Sindhi serves as a poignant reminder of the rich tapestry of human history, weaving together threads of identity, migration, and resilience. While the significance of Memoni is evident to the community, it remains largely unrecognized by scholars. By bringing attention to this subject, we have the opportunity to improve the relationship between the mainstream Sindhi community and its daughter community, which, due to unfortunate political reasons, has been relegated to the status of a minority, despite historically being part of the majority. This effort would not require the Memons to compromise on their distinct Sindhi dialect. Instead, it calls for awareness and education within the community to recognize the roots of Memoni in Sindhi and reconsider their ethno-political identity.

By embracing Memoni and acknowledging its Sindhi roots, Sindhi scholars have an opportunity to bridge the gap and forge a stronger bond between the Memons and the mainstream Sindhi community using language as a tool

Such an endeavor to change attitudes requires a scientific and precisely anthropological approach coupled with in-group activism in order provide the Memon community’s youth with a

sense of belonging to the land their ancestors once called home but also power and pride of being part of a majority with which they share their DNA rather than sliding to the minority or claims to a separate identity. It would offer them the promise of security and whole-hearted acceptance by their Sindhi neighbors, while also revitalizing their precious language and promoting it as a recognized dialect of Sindhi, which it truly is. Additionally, it would grant them socio-political advantages by assimilating into the mainstream Sindhi culture. For Sindhis, this welcoming approach would not only increase the Sindhi community’s membership from another two million worldwide Memoni speakers out of which at least one million reside in Sindh, but also contribute to resolving the ethno-linguistic crisis faced by Sindh’s own citizens. It would foster loyalty from a highly productive group for the common good of both communities. By embracing Memoni and acknowledging its Sindhi roots, Sindhi scholars have an opportunity to bridge the gap and forge a stronger bond between the Memons and the mainstream Sindhi community using language as a tool.

While anthropology in Sindh and throughout Pakistan has gained popularity, extensive anthropological research on the Memons, unlike their genetically related communities, the Ismaili Khojas and Lohana Hindus, remains limited. The assimilation, acculturation, remigration, and identity construction of the Memons, as well as their shift towards Urdu, remains a tantamount of fascination for anthropologists. The community’s adoption of Urdu poses a significant challenge not only to the Memons themselves but also to researchers and Sindhi linguists who face the threat of losing a Sindhi offshoot language. While the official website of the World Memon Jamaat recognizes in a statement which reads: ‘Memoni is believed to have originated from Sindhi’, a big fraction the community’s younger population is in a state of denial of its roots with a dim bias towards Sindhi or worse, Memoni. Linguistic Anthropology can play a significant role in solving this crisis between both communities by implication of anthropological advocacy, vocalization and applied anthropology within the Memon community.

While anthropology in Sindh and throughout Pakistan has gained popularity, extensive anthropological research on the Memons, unlike their genetically related communities, the Ismaili Khojas and Lohana Hindus, remains limited. The assimilation, acculturation, remigration, and identity construction of the Memons, as well as their shift towards Urdu, remains a tantamount of fascination for anthropologists. The community’s adoption of Urdu poses a significant challenge not only to the Memons themselves but also to researchers and Sindhi linguists who face the threat of losing a Sindhi offshoot language. While the official website of the World Memon Jamaat recognizes in a statement which reads: ‘Memoni is believed to have originated from Sindhi’, a big fraction the community’s younger population is in a state of denial of its roots with a dim bias towards Sindhi or worse, Memoni. Linguistic Anthropology can play a significant role in solving this crisis between both communities by implication of anthropological advocacy, vocalization and applied anthropology within the Memon community.

Where Sindhi language itself has a threat in urban centers, joining hands with another ethnically and linguistically Sindhi group can embolden Sindhi language by multiplying its strength in facing the challenges posed by Urdu and English. Where traditional Linguists and Scholars have kept back on such an important issue or to provide a solution to the shrinking of Sindhi first language speakers to central Sindh, the assistance and problem-solving skills of Anthropologists in this particular matter can be employed to bring an impact in a linguistic conundrum.

_______________________

Bakhtyaar Shahzad Panwhar Linguistic Anthropologist. He is fluent in Sindhi, English, Urdu, Siraiki, Punjabi, Gujarati, Kutchi, Marathi, Bangla, Persian, Arabic, Hindi, Dhatki, Kohli Parkari (semi fluent in Spanish and Hebrew). He did BS Anthropology- Dec, 2022 from University of Sindh. His areas of interest are Anthropology, Sociolinguistics, Phonology, Historical and Comparative Linguistics, Culture. He can be accessed at Email: bakhtyaarshahzad@gmail.com

Bakhtyaar Shahzad Panwhar Linguistic Anthropologist. He is fluent in Sindhi, English, Urdu, Siraiki, Punjabi, Gujarati, Kutchi, Marathi, Bangla, Persian, Arabic, Hindi, Dhatki, Kohli Parkari (semi fluent in Spanish and Hebrew). He did BS Anthropology- Dec, 2022 from University of Sindh. His areas of interest are Anthropology, Sociolinguistics, Phonology, Historical and Comparative Linguistics, Culture. He can be accessed at Email: bakhtyaarshahzad@gmail.com