The poet and her translators Rekha Sachdev Pohani, Barkha Khushalani and Shobha Lalchandani talk about the project

By Suhit Bombaywala

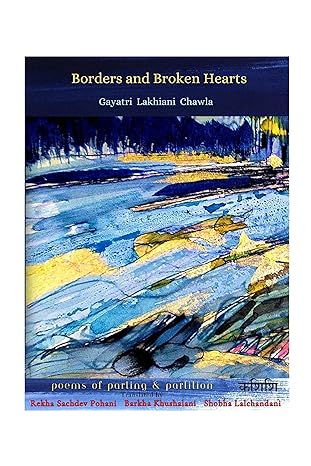

Borders and Broken Hearts features the poetry of Gayatri Lakhiani Chawla translated into Sindhi, presented in both the Devnagari and the Perso-Arabic scripts. The poet and her translators Rekha Sachdev Pohani, Barkha Khushalani and Shobha Lalchandani talk about the project

The post-Partition Sindhis’ longing for Sindh, a homeland never seen, but fashioned in the imagination from stories and memories, is featured in the recently published Borders and Broken Hearts: A Trilingual Collection of Poems on Parting and Partition, a collection of poetry by Gayatri Lakhiani Chawla, who lives in Mumbai. The book represents her engagement with her community’s history of displacement, adaptation, loss and nostalgia. While acknowledging her generation’s place in contemporary India, she cherishes and nurtures the “Sindhyat” in herself and others and sees her community’s suffering in the light of a universal suffering, namely, that of the parting of lovers.

This volume features her poems in English as well as translations into Sindhi (Devnagari script) by Rekha Sachdev Pohani and Barkha Khushalani. The translations also appear in the Perso-Arabic script rendered by Shobha Lalchandani. This bilingual and multi-script approach is an attempt to acknowledge and make space for plurality in the community. The poet and translators discussed these and other points in a joint interview.

How do you, as contemporary Sindhis in India, approach Partition and longing for the ancestral homeland?

Gayatri Lakhiani Chawla: The ancestral homeland will always be dreamlike, a picturesque place I have not visited, and wish to visit in this lifetime. The need to belong still plays an important role. It’s a feeling deep rooted in our souls. But not all memories are terrible; there are some valuable friendships and sweet memories basking in the warmth of the sun in the passage of time as well. I think keeping the essence of Sindhyat intact along with preserving the nostalgia and imagery of Sindh in the numerous stories, folklore and the poetry of Shah Abdul Latif and the kalaams of Sachal Sai is essential. A faint memory has stayed with me: the last day of school, me returning home sadly and asking Papa, where is our gaon? Apparently, everyone was heading to theirs.

Rekha Sachdev Pohani: I have never seen the homeland. But I have heard elders, poets and people around me speak of it. I feel I have been there. I do have the desire to see Sindh once in my life. Sindhyat means mitti ki khusbhu for me, as does Sindhi culture, food, love stories.

Barkha Khushalani: We grew up in a typically Sindhi background with Partition stories being told to us. Our parents spoke about the Sindhi spirit and adaptability. I have seen my father crying while watching Buniyaad (A popular Doordarshan serial, 1987-88). He would tell us about his friends and the assets and property (he had a building in his name, ‘Thakur Niwas’) in Karachi that were left behind. They never thought they would never return to Sindh. My father had even hidden the keys to his palatial house in the water tank on the terrace, assuming he would need them once he returned. But that never happened.

Longing, yes, I yearn to go and visit the places where my ancestors were born. As my father would talk about his haveli in Ranipur, for many years a haveli appeared in my dreams. Surprisingly, I stopped dreaming about it after my father passed away in 2013.

I would love to go to Sindh. In fact, it is a dream to attend the Karachi Literature Fest or start a similar fest in India.

Shobha Lalchandani: The atmosphere of our house was filled with everything Sindhi. My parents devoted their lives to the preservation of the Sindhi language and culture. My mother would sing Shah Abdul Latif’s couplets while doing her household chores like cooking and cleaning. She was a singer who sang mainly Sindhi folk and kalaams and didn’t ever refer to a diary, as she knew at least a thousand songs by heart. Father wrote short stories in Sindhi. So we grew up in a beautiful sangam of Sindhi music and literature.

My family has been my support system. My husband Ram Lalchandani was a commercial artist and designed the covers for almost all the Sindhi books that were published here. He encouraged me to pursue my Masters in Sindhi language and inspired me to accept the challenge of becoming the editor of Hindvasi, a Sindhi weekly newspaper. My children Anand and Amrita do their bit towards Sindhi language too. Anand now designs covers, makes illustrations and typesets Sindhi books, and Amrita reads and writes Sindhi, apart from being a very good singer of Sindhi Sufi kalaams. All my grandchildren too are keen learners of Sindhi. My daughter-in-law Aneesha has developed an interest in Sindhi and has started writing Sindhi poetry. The main thing is the atmosphere in the house which involves every individual.

I have been very fortunate to have visited Sindh in 2004 on the invitation of Sai Sadhram for a religious function.

What was the idea behind enabling the transcription of the poems into the Devnagari script and the Perso-Arabic script too?

Gayatri LC: The idea or the reason for keeping both the scripts was to place both scripts before Sindhi readers, symbolizing a kind of similarity within the differences. Also, it was visually appealing to have three scripts on a single page like three sutradhars narrating the same poem in different ragas. Moreover, it was invigorating to see how the Perso-Arabic script runs from right to left instead of the usual left to right – a confluence of sorts. The book has both the Perso-Arabic script and the Devnagiri script, giving the poems the timeless quality that is akin to Sindh itself.

What does Sindhyat mean to you? And in what ways does the book explore Sindhyat?

Gayatri LC: Sindhyat, along with its rich culture and heritage, is a way of life. There is an inner need to preserve the language, hence a constant use of it at home while interacting with the younger generation is another step of embracing the universal quality of Sindhyat. Borders and Broken Hearts is a visual journey where the readers not only read but also interact with all the scripts. One such priceless moment was when I read my poem Leaving Sindh at an event on Partition; it was riveting to have people from the audience responding to the poem.

Barkha K: Sindhyat is a way of life for me. Our parents both were writers and promoted Sindhi language through vocal culture and would arrange Sindhi Sangeet programs and encourage artistes from all over India to perform in Mumbai. Our parents’ generation had a valid reason for their inability to preserve the language and culture as they had to start their lives afresh and survival was important. But after all the hardships, the community managed to get Sindhi language included in the 8th Schedule of the Indian Constitution in 1967. I feel we are answerable to the next few generations about the language, so we need to gear up. The need of the hour is to make Sindhi language as fashionable as our cuisine and music is.

Shobha L: Sindhyat for me is like breathing. Whatever we do for Sindhi language and culture is a tribute to our parents. We will continue our endeavors in the form of music, seminars, drama and films. In the coming days, social media will play a big role to enable us to keep Sindhyat alive. I have memories of our house being an adda, a meeting place for Sindhi artistes, be it singers, music directors, lyricists, stage actors and musicians. Each one would showcase their talent and my parents, too, would participate. Together, they would plan the next Sindhi Sammelan, seminar, sangeet program and drama.

Gayatri, it is fascinating to know how a book comes together. Did the poems accumulate gradually, or did the book take shape as a project? And how did the translators divide the work?

Gayatri LC: The poems were written gradually over the years. As I was interested in the theme of Partition because of my father’s history, I got drawn towards its repercussions. I tried to bring reasoning to the grief, to questions on identity and emptiness. Father was born in Manjhu in Sindh, Undivided India, and his stories unconsciously seeped into my psyche and my writing. Probably that’s why our thinking was layered and often fragmented. I recollect my father saying always, “We are not refugees”. Was he in denial, I would wonder.

The project was started pre-pandemic, when I approached Rekha Pohani to translate some of my poems from English to Sindhi in the Devnagiri script. After the pandemic, the project was recommenced with Barkha Khushalani and Shobha Lalchandani on board. It was team work and a blessing to find translators with the same creative frequencies.

Rekha Pohani and Barkha Khushalani translated my poems from English to the Sindhi Devnagiri script. They are both well versed with the script and its characteristics.

Shobha Lalchandani has a flair for writing in the Perso-Arabic script and a particular fluency in the language, hence I approached her to do justice to my poems in the original script.

The book is published by Haoajan publishers, Kolkata, headed by the husband-and-wife duo of Mridula and Sarbajit Sarkar.

The collection is intriguingly named Borders and Broken Hearts: A Trilingual Collection of Poems on Parting and Partition. Gayatri, could you perhaps share the poetic idea underlying “parting and Partition”?

Gayatri LC: When the idea of translating Partition poetry into both the scripts came about, I thought of the multiple mixed feelings that one would experience – feelings of isolation, nostalgia, angst and hurt that were much like the feelings of pain when one parts from a loved one or loses a beloved. The scars from both are deep and harsh, staying with us forever.

How does one define pain? It’s immeasurable, and I would think the only way out is healing. I don’t know if we can really airbrush the memories of the Partition, but we could try by sharing stories and manifesting for peace in our personal struggles with history. That is how the idea of the title cropped up. So, the collection has poems of loss and longing along with the Partition poems. Not to forget some poems with the quintessential theme of love.

Rekha and Barkha, I don’t know Sindhi; an attempted reading of Sindhi versions in Nagari script suggests the poems are more mellifluous, with more words and “heavier” lines. Please share your experiences and considerations in translating the poems into Sindhi?

Barkha K: Yes, you are absolutely right, Sindhi language has a music in it which sounds sweet and smooth, and these poems have an emotional depth. My personal opinion is that translation from the mother tongue to English aids in connecting to a wider audience. It allows the growth of new ideas and the spread of information across cultures. From English, it is possible to transcreate the literature into many other foreign languages so that they can be read in many other countries.

Rekha SP: When Gayatri brought this project to me, I was unsure if I would be able to do justice to it. This is my first translation. I am happy to see the book has come out beautifully.

Shobha, would you please share how you developed an interest and skill at writing the Perso-Arabic script? Coming to this book, its foreword by poet and editor Menka Shivdasani quotes Asha Chand (president, Sindhi Sangat) as telling HT that Sindhi has 52 alphabets and Nagari has only 33. Would you like to elaborate on the challenges of using Nagari?

Shobha L: I was fortunate to have started early as I went to a Sindhi medium school and was taught Arabic script. I had never imagined that learning our script would qualify me to become the editor of a Sindhi weekly newspaper. I am comfortable with the Arabic script and know reading and writing in the Devnagari script too. As a matter of fact, Devnagari is easier to learn as the basics of Hindi and Marathi are applicable to Sindhi Devnagari script except for few additional alphabets in Sindhi.

As most of our literature is available in the Arabic script, we have the uphill task of recreating it into Devnagari script, which we two sisters have started doing. As I see it, the need of the hour is to begin with speaking Sindhi at home and then giving a choice of scripts – whether it is Arabic, Devnagari or Romanized Sindhi – to the new generation. We are prepared to teach them.

Multiple poems on homesickness refer to Sindhi customs: the old man kneading papad dough is visited by “ghosts of solitude” from Karachi; the old woman, sewing an ajrak mattress, sings a composition by Sachal Sarmast. In what other ways does the past come to memory in your daily routines?

Gayatri LC: Memory is a genetic disorder, and the limitations of the heart and mind are the reasons we document our lives and continue reciting our oral histories to the next generation to keep Sindh alive. History can never be erased since it’s already written, it’s already a part of our persona. I spent months co-translating the kaafiyu of Sindhi Sufi poet Sachal Sarmast. It became a daily routine of my writing life. In everyday life, the past is always present whether it is in the Sindhi curry recipe passed down from one generation to another, celebrating Teejri now with the new age pooja on YouTube, or in the vintage glass Burma teak cabinet, an heirloom carried to Bombay during the Partition.

Barkha K: At every stage, my mind is flooded with memories: my mother Paru Chawla singing Sachal Sarmast’s kalaams and my father proudly telling us that he is from Daraza, the birthplace of Sachal Sarmast.

Gayatri, this collection mentions food perhaps more often than your previous books. The papad, mango pickle, turnips and julienned carrots “left to sour and pickle” by fleeing families (and in the next poem, a turnip pickle, which you do get to eat), to plum beetroots, to vivid evocations of brewing tea, whether chai or blue pea flower (aprajita) tea. I am curious to understand how, in these poems of parting and Partition, food evokes an emotional pitch for you. Does food in these poems comfort or does it also refer to something else?

Gayatri LC: There has always been an emotional connect with food. It could be the afternoon spent hiding and eating mitthi aam ka achar after school, the stories of Karachi that Papa would narrate as he juggled with the gauvas or the simple practice of offering papad and water to him when he returned home. Food is truly comforting and, in an instant, you are transported to the multiple memories attached to it. Food does have that quality to take you back in time and sometimes relive those moments. As poets, we have the tendency to look beyond the vision and align finely with our human senses, helping us to manoeuvre, create and join the dots. Words like papad, chai and mango pickle naturally flow into my writing since they are symbolic of a time, age, culture and literature.

Barkha K: I have vivid memories from the 1960s of Sindhi papads being prepared in our home. My grandmother would knead the dough, mummy would roll it into wafer thin papads, and we, the children, would dry them in the sun on a newspaper spread in the balcony. The last step of counting and storing in steel dabbas was left to the children. And how we loved to rotate the ceramic container filled with freshly made pickle by our grandmother! The tossing of the ceramic bharni was to mix the spices well with the mustard oil. I can never forget the flavour of wheat atta laddoos prepared by our grandmother during the winter, and how we loved to roll them round.

Gayatri, your interest in the supernatural – among other things, you read the tarot and other decks of cards – appears in multiple poems, notably Winter and Iris. Would you please describe how these particular poems were inspired and written?

Gayatri LC: Winter is a poem on healing so it talks of how one can bring closure to the pain associated with losing a beloved. Memories will always stay but “cutting the cord” is important. As a healer, I associate with a lot of grief-stricken stories of clients and a ritual that I recommend for healing is “cutting the cord”.

Iris is a poem with a mythological twist featuring Jhulelal, the water god, who is an incarnation of Lord Varuna. He is the deity of the Sindhi community.

For both these poems, the inspiration came from voices and I felt there was a message that needed to be decoded; a message of love and healing encapsulated in the form of my poetry.

________________

Courtesy: Hindustan Times (Posted on September 29, 2023)

[…] Also read: Longing for a homeland never seen […]