Based on her travels, the book looks at the significance of Sati’s suffering and sacrifice

Khan completed her book in the beginning of July 2018. As the month ended, she was found dead in her apartment in Karachi. According to reports in Pakistani dailies, it is believed she died of asphyxiation after setting a pile of books on fire.

Diya Kohli

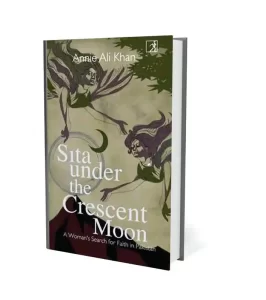

This is a book that takes the reader to remote and violent corners of Pakistan where the land is marked by the blood of its people. Here, away from the urban centers, superstitions abound and the search for faith is seen as a way out of present circumstances. “All is momentary, all is pain”, wrote Qurratulain Hyder in her 1959 novel River Of Fire. Sixty years later, it is journalist and writer Quratulain “Annie” Ali Khan who carries forward the complex interaction between history, war, politics and faith in her debut work, Sita under the Crescent Moon.

Khan completed her book in the beginning of July 2018. As the month ended, she was found dead in her apartment in Karachi. According to reports in Pakistani dailies, it is believed she died of asphyxiation after setting a pile of books on fire.

Like many posthumously published works, the book is a poignant reminder of the writer, for it is a travel memoir and personal spiritual quest from Lyari in Karachi to Hinglaj in Balochistan and Thatta in Sindh. It is also a chronicle of the larger spiritual journey of numerous women in Pakistan seeking peace, comfort and release from their material existence. She writes in her foreword, “It was truth I sought as I made my passage into Balochistan, armed with a notebook, camera and audio recorder, with a vague outline of a story in my head…. The search for the elusive sati became a quest to learn more about the legend of women burned or buried and then worshipped…”

Her journey begins at the shakti peeth of Sati at Hinglaj. Thereafter, as she travels across the country, the world of Sati temples and Sufi shrines coalesces. Khan travels with other female pilgrims to shrines across Pakistan as they search for ways to love, let go of grief, worship, fulfil their deepest desires and cure themselves. Along the way, she strikes up friendships with poets, female fakirs (religious ascetics), those who are possessed, those who heal and those who just pray—women who have been broken by the world of men and have slowly rebuilt themselves piece by piece. These worshippers fuse different elements from across Hinduism and Islam. As a result, sacred snakes, Durga idols and shivlings coexist with Islamic rituals and practices.

Khan comes alive in the pages as a journalist on a mission, navigating harsh terrain and remote towns in a country that is less than easy for a solo female traveller. She is the political narrator who views the country’s changing contours through the history of partition, coups and regime changes.

Her travel shows that the ravages of war are often borne by women and children. For these women—marginalized, rejected and without a voice, agency or means—it is faith that remains an alternative as well as last resort to normative social roles. It is within such a context that she understands the significance of the goddess Sati as an emblem of sacrifice, suffering and freedom—the goddess who is as benign as she is fierce. She is one who will possess your mind, body and soul and also free you from the endless cycles of suffering. And she is a constant reminder of the search for a greater truth and the fact that truth always comes at a price.

Her travel shows that the ravages of war are often borne by women and children. For these women—marginalized, rejected and without a voice, agency or means—it is faith that remains an alternative as well as last resort to normative social roles. It is within such a context that she understands the significance of the goddess Sati as an emblem of sacrifice, suffering and freedom—the goddess who is as benign as she is fierce. She is one who will possess your mind, body and soul and also free you from the endless cycles of suffering. And she is a constant reminder of the search for a greater truth and the fact that truth always comes at a price.

After witnessing a dhamaal (a religious ceremony that combines rhythm, remembrance and meditation) to cure a young girl possessed by Shah Pari, Khan writes: “That’s how it was, the love of a sati. It never left a woman’s heart. The Mai brought happiness. The Mai brought pain. She was a possessive lover. Her love was the light of life. Her love was death and destruction.”

By no means is Khan’s book an easy read. Its prose is rambling and contains themes and a narrative that sometimes unravels into a stream of consciousness prose. Typos abound, as do syntax inconsistencies. Shrines, symbols (the serpent is a recurring one), caretakers, fakirs and ecstatic dhamaals fuse into one another. Characters appear and disappear throughout its 300-odd pages—as spectral and mythical as the worlds to which they belong.

This is a work that reads like a first draft and a final book at the same time even though it has been edited with love by Khan’s friend, Manan Ahmed Asif, and Rajni George. However, even in its messy, less-than-perfect form, Sita under the Crescent Moon gives a voice to the hundreds of women who remain unheard. It follows their tales of emancipation through roads less travelled. It is also a chronicle of Khan’s own journey towards the truth. And it is in the telling of these intertwined stories that the book pays its dues to Sati—the woman who became a goddess.

__________________

Courtesy: Live Mint