The information war may now have moved online, but the postcards of 1905 should remind us that little else about current propaganda is new.

Tobie Mathew

In 1878, Russian mail workers intercepted four postcards sent from Moscow to St Petersburg. Each contained a series of short codes relaying chess moves, paired with an innocuous-sounding message. One, dated 29 October, reads: ‘Our club is growing, but the players are all bad – we haven’t yet had a single decent game.’

Across a covering note describing the postcards as suspect, an agent of the secret police has scrawled: ‘Chess!!!’ – The three exclamation marks pouring scorn on the notion that the messages might have anything to do with board games. This Imperial policeman was convinced that the king these players were maneuvering against was in fact the tsar himself.

Chess-themed conspiracies were one of many problems to beset the authorities following the arrival of postcards in Russia. Even before they were introduced, postal officials worried they might give rise to ‘unpleasant confrontations between government servants and the public’. But little could have prepared them for the onslaught of messages that followed.

The postcard medium did far more than provide a cheap and convenient way for the revolutionary underground to communicate – it brought the popular voice within earshot of the Imperial regime. Downtrodden subjects, such as Pavel Evstifev, who in 1898 sent a postcard complaining to his local council about having to pay for grazing rights, now had their own paper soapboxes: ‘Why are we not given grass and forest land for free?’, he demanded. ‘You are rich and stuff your pockets, while we get nothing at all.’

It had been just a few decades since access to printed material had begun to extend beyond the elite, but already powerful new spaces were being created that the state was struggling to control. Such was the scale of the problem that the Interior Ministry contemplated banning postcards altogether.

In the late 19th century the humble postcard became a modern tool of mass communication. Momentous technological advances in paper production and printing shrunk the world, giving the wider population a voice and offering a raft of new opportunities to subversives and propagandists.

For Russian revolutionary groups, the growth of the print industry not only expanded their reach, but also helped them to establish new ways of raising money. Activists, most of whom were based abroad, depended heavily on donations, but publishing proved one of their most reliable sources of income. Surprising though it may seem, most early opposition material was sold, as opposed to given away.

The autocratic government had its own firewalls in place to stop propaganda coming into the country. Known to posterity as ‘black cabinets’, these were secret offices that conducted perlustration of the Imperial mailbag. Nonetheless, officials struggled to stem the torrent. Inflammatory material produced by groups in exile streamed from the cities of Western Europe into the Russian Empire.

In the early 1900s, the situation inside the Empire started to deteriorate. The industrial revolution that boosted the publishing industry was also greasing the wheels of political dissent. In January 1905, following a disastrous war against Japan, striking workers in St Petersburg were shot down while on a march to the Winter Palace. The bloodshed set off a full-blown revolution.

Bloody Sunday, as it became known, provided a focal point for discontent across the country. With little possibility of publicizing news of the killings in the press, illegally produced picture postcards became one of few ways that the population could get to see the other side of the story.

The revolutionaries were single-minded in spreading their message. ‘Dear Colleague, please send postcards and photographs of the events in St Petersburg – as many you can, without delay’, wrote one revolutionary a few weeks after the massacre. This demonstrates the speed with which postcards came into service after Bloody Sunday and how quickly they spread, not just across cities, but whole provinces.

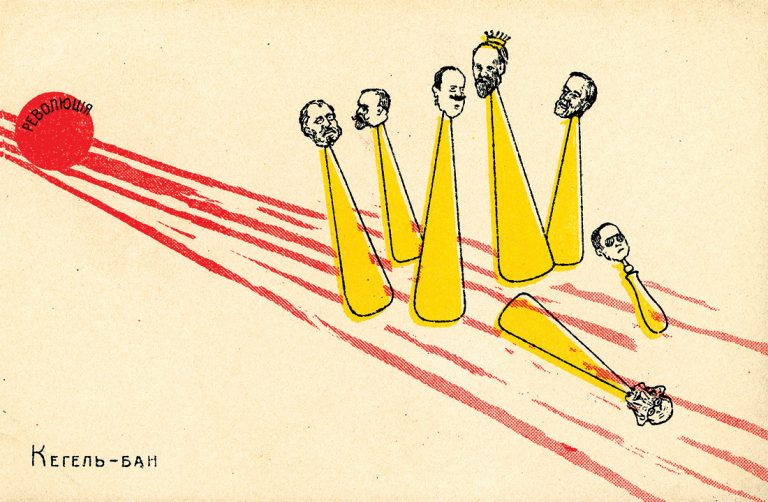

Easy to produce, distribute and comprehend, picture postcards spread like modern memes and they were at their most persuasive when conveying a single, compelling idea. The best showed events in Palace Square, where, against a backdrop of the Winter Palace, mounted Cossacks charged down innocent protesters.

These emotive images belied the complications of the period. No matter that most of the shooting took place elsewhere, no matter that some of the marchers may have been armed. These visuals passed over all the inconvenient facts.

Throughout 1905, opposition groups continued to pour out anti-tsarist invective. Among the most widespread were images depicting St Petersburg Governor Dmitrii Trepov, whose infamous command to troops – ‘Don’t spare the bullets and don’t use blanks’ – was reproduced endlessly in postcard satires. Dark humor was often a key element: one card titled ‘Long Live Freedom’ depicts soldiers brutally dispersing a peaceful demonstration.

Contemporary authorities may wring their hands over the online videos that have brought warzone atrocities into adolescents’ bedrooms, but it was postcards that first brought the violence of the street into the safety of the home. In 1905, they served the role that social media does today, allowing revolutionaries to construct alternate realities, which enabled them to ridicule their opponents, radicalize their sympathizers and speak directly to the nation as a whole.

The political messages expressed in postcards could be hugely effective in undercutting the official narrative. The revolutionaries played fast and loose with the facts, preferring to show what they construed as a ‘greater truth’: the inherent immorality of Europe’s last absolutist regime. The dramatic imagery, humor and word play were about capturing the heart, not the head.

The information war may now have moved online, but the postcards of 1905 should remind us that little else about current propaganda is new.

_____________________

Tobie Mathew is the author of ‘Greetings from the Barricades: Revolutionary Postcards in Imperial Russia’ (2018).

Courtesy: History Today