This essay will seek to show the trends of organization, regionalized recruitment policy, and institutional unification of the British Indian Army and how these trends were reproduced by the Pakistan Army after 1947.

Syed Hussain Shaheed Soherwordi

School of History & Classics, University of Edinburgh

A colonial army had to serve colonial masters

Up to and including the first half of 1928, vacancies were filled by nomination, after that date by examination. It was first decided to admit Indians and Anglo-Indians to Woolwich in 1928, and, by 1929, nine vacancies were offered. But there were only two successful candidates. Similarly, the first examination for Cranwell was held in November 1928 and, by the end of 1929, twelve vacancies had been offered but only six filled. Ayub Khan was also chosen for training as a commissioned officer at Sandhurst. He did remarkably well, securing the top position among the Indian cadets. Among his colleagues was General J. N. Choudhry who later became C-in-C of the Indian Army. The demand for the Indianisation of the forces did not end with the submission of the Skeen report. The issue was taken up once again during the Round Table conference when its sub-committee on military affairs made a demand on similar lines, including setting up a military college in India on the Sandhurst model.

Finally, the struggle was accomplished in the shape of the establishment of an Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun in October 1932. Its first batch, commissioned in 1935, were called Indian Commissioned Officers (ICOs). After the Second World War, the Eight Unit Scheme was brought to an end, and all the branches of the army were opened to Indian officers. Training facilities at Dehra Dun were expanded. A large number of officers were recruited on short and long courses (short and emergency commissions). By early 1947, out of 9500 Commissioned Officers, about 500 were pre-war KCOs and ICOs. Only nine Indians (five non-Muslims, four Muslims) reached the senior rank of Lt. Colonel during World War II. Out of four Muslim Lt. Colonels, one was appointed temporary Colonel and one acting Brigadier. A few days before independence, the acting Brigadier Muhammad Akbar Khan was promoted to the rank of Major General. Promotions were given on similar lines to others in the substantive ranks below that of Lt. Colonel. The officers recruited during the war period were in junior positions. Ayub Khan was then a Brigadier in the Indian Army and was attached to the Boundary Force, under Major General Rees. In January 1948, five months after Independence, he was posted as General Officer Commanding (GOC) of 14 Division in East Bengal. The army was always a very special and private concern of the British in India. They kept it away from any kind of politics. Rather, in case of any clash between the country’s politics and security, they favored the latter. Even as late as 1946, the Viceroy’s civilian Executive council had no powers over defence and the defence budget. The British Indian Army was kept free from a strong influence on Indian politics as there was no synthesis between the two. Defence had nothing to do with the politics of the country. Thus the British-Indian Army proved an autonomous entity. Their training (discipline and professionalism) and separation from the society strengthened their organizational ties and loyalty to the British authority. The army’s administrative and professional powers were concentrated in the hands of the Army chief, who after the Curzon-Kitchener dispute emerged autonomous in military affairs. This was the beginning of the exclusion of army matters from civilian control.

Ayub Khan was Brigadier in the Indian Army and was attached to the Boundary Force, under Major General Rees. In January 1948, five months after Independence, he was posted as General Officer Commanding of 14 Division in East Bengal.

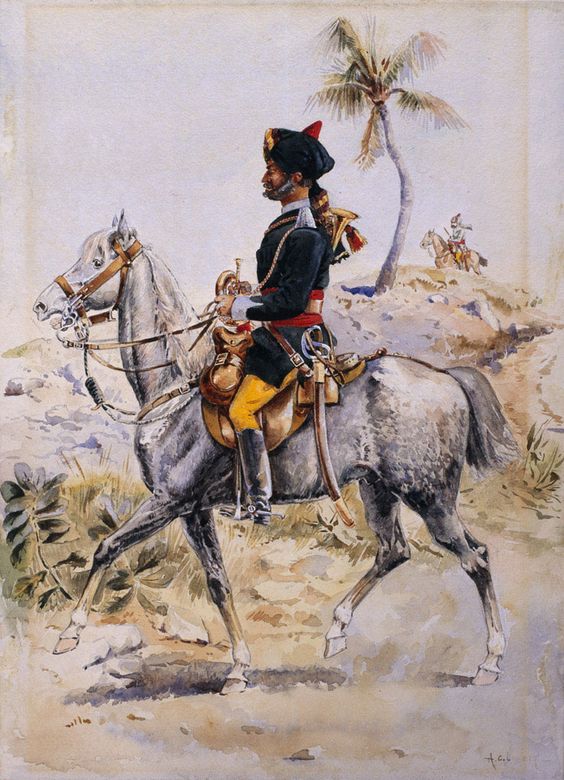

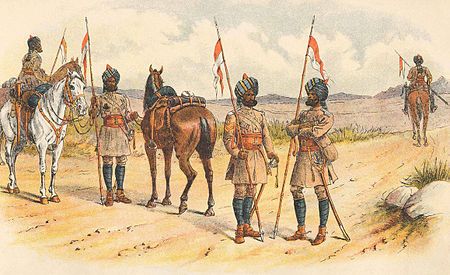

The contest between the Mulki Lat Sahib [Curzon] and the Jungi Lat Sahib [Kitchener] weakened forever the once great influence of the Viceroy of India. It is interesting to note here that most of the Governor Generals and Viceroys of India were formerly military officers. One Governor – Robert Clive (Dec. 1756- Feb. 1760, April 1765-Jan. 1767) – and three Governor Generals – Lord Cornwallis (Sept. 1786-Oct. 1793 and July 1805-Oct. 1805), the Marquis of Hastings, Lord Francis Moria (Oct.1813- Jan. 1823), and Lord William Bentinck (1828-35) – functioned as C-in-Cs. Field Marshal Sir Archibald Wavell, C-in-C, 1941-42, 1942-43 was promoted to the post of Viceroy in 1943, a position he held until March 1947. At this time, few could have imagined that this trajectory would later be used by junior officers as a short path to become military rulers of the future state in the Indian politicians made several demands for legislative control over defence forces, the defence budget and foreign policy during the 1920s and 30s. Any such control by the politicians would have been a British nightmare. Politicizing the British Indian Army was the last thing the British could ever imagine. The Esher Committee (1919-20) maintained that the Indian Army was a unit in the security system of the British Empire and that its administration could not be dissociated from the total armed forces of the empire. There were many political activities that provided acid tests for the army, but the Army personnel held on to their professional ethos and stood by the British administration. The Punjab, with its hardy and martial rural population of peasant proprietors, had, since its inclusion in the Empire, been rightly regarded as the “Shield”, the “Spearhead” and the “Sword-hand” of India. ‘It earned such proud titles due to its association with the British Army and help in every Eastern campaign from the Mutiny down to the present day’. A colonial army had to serve colonial masters. The autonomous nature of the colonial army chief and military affairs remained unchanged even after the independence of Pakistan.

Conclusion

This essay has provided a historical overview of currents and trends of the British Indian Army. These developments transformed a segment of the British Indian Army into the Pakistan Army. The impact of the 1857 Uprising on regional recruitment to the British military played a large part in the de-Bengalisation and consequent Punjabisation of the Colonial Indian Army; a punishment for Bengal as a region that had rebelled and a reward to the Punjab that aid in the suppression of the Uprising. As a result, it is argued that this shift gave civil and military leadership to the Punjab after the partition, which contributed to Punjabi dominance over other provinces following independence.

Historically, 65 to 75% of the Pakistan army was drawn during the 1950s and 60s from the same areas of the Punjab where the British formerly used to recruit. This was the culmination of the Punjabisation of the Army initiated by the British during and after the Mutiny war of 1857.

The post-partition Indian security threat to the newly carved out Pakistan, as well as the first Kashmir war of 1948, resulted in an increase in the Pakistan Army’s strategic importance within the country. Security against India became the raison d’etre of the Army. The military leadership and political administration considered it necessary to strengthen the army against any potential security threat. The political forces of the country, due to the fear of India, also accommodated the Army in the national and international decisions of the government. This encouraged it to increase its political influence.

Historically, 65 to 75% of the Pakistan army was drawn during the 1950s and 60s from the same areas of the Punjab where the British formerly used to recruit. This was the culmination of the Punjabisation of the Army initiated by the British during and after the Mutiny war of 1857. However, even after independence, the Pakistan Army was still following the trend set in colonial times – recruiting more Punjabis and discouraging Bengalis. That is one of the main reasons why despite constituting 56% of the total population of Pakistan, Bengalis made up less than 7% in the Pakistan Army during the 1960s. The Pakistan Army always demonstrated a lack of trust towards Bengalis, as had the British, and doubted their loyalty to the state. This further alienated them from the ranks of governmental administration.

The Pakistan Army borrowed numerous other autonomous features from the British Army. Intensive training with an emphasis on discipline and efficiency and their separation from the fragmented Pakistani society turned the Pakistani soldiers into a professional, united and autonomous fighting force. However, they formed a force parallel with the government of Pakistan. As the country was a security-oriented entity, any important decision taken by the initial governments of Pakistan needed a nod from the Army’s General Headquarters (GHQ). The meeting of the Corps Commanders turned into a kind of a domestic and foreign policy reviewing committee. Sought in the name of Islam and democracy, Pakistan was moving closer towards the form of a military dictatorship.

The Pakistan Army borrowed numerous other autonomous features from the British Army. Intensive training with an emphasis on discipline and efficiency and their separation from the fragmented Pakistani society turned the Pakistani soldiers into a professional, united and autonomous fighting force. However, they formed a force parallel with the government of Pakistan. As the country was a security-oriented entity, any important decision taken by the initial governments of Pakistan needed a nod from the Army’s General Headquarters (GHQ). The meeting of the Corps Commanders turned into a kind of a domestic and foreign policy reviewing committee. Sought in the name of Islam and democracy, Pakistan was moving closer towards the form of a military dictatorship.

During colonial rule, the swelling defence budget was a prerequisite for keeping a strong British Army against internal and external threats. However, this practice was continued by the Pakistan Army at the cost of the development of civilian sectors. The defence budget grew in the name of a perceived Indian threat. If the nation could not provide enough for development of the Army, military alliances were signed with the US to muster more resources. Whatever the plight of the nation, the Army remained a well-developed, well-nourished, well-trained, well-equipped, well-organized, united and well-off autonomous institution within Pakistan. The manner in which the British Indian Army was groomed within the province of Punjab ultimately enormously affected Pakistan. At the time of partition, relatively but significantly speaking, Pakistan had neither a bourgeoisie, nor a strong middle class. It lacked a business class. The Punjab was the power center of the country, but it lacked an industrial establishment. Aitzaz Ahsan contends that the British intentionally kept the Punjab industrially backwards as it might have affected recruitment if other means of livelihood, except agriculture, were available to the Punjabis.

The tradition of British military recruitment in the North West of the subcontinent (Punjab and NWFP), was a major factor in the emergence of Pakistan as a quasi-militarized country.

The absence of a Bourgeoisie increased the influence of feudal elites. The landowning aristocracy were in favour of the British due to the benefits they received from them in exchange for contributing Jawans and Sawars to the Army. Thus, the tradition of British military recruitment in the North West of the subcontinent (Punjab and NWFP), was a major factor in the emergence of Pakistan as a quasi-militarized country. It was a country with a weak political structure, feeble political parties and politicians, but a strong feudal class and civil and military bureaucracy. This naturally ‘consolidated the linkages between the military service, agricultural land and political power’. Hence the Muslim League, due to its weak control within the newly created country, had to abdicate in favor of a stronger giant, the Pakistan Army. With the firm support of the feudal class, more agricultural land under its domain, and with its organizational and professional culture, the Pakistan Army began to assert its political role in the hub of the country’s politics. The irony of fate is that it lacked political training. Hence, the Army ran the country like a defence establishment by increasing the defence budget, having defence pacts, and appointing defence services people in the policy making bodies of the country, with effects that ultimately were to be deleterious in the future development of the county. (Concludes)

__________________

Courtesy: Centre for South Asian Studies, School of Social & Political Science, University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

Click here for Part-I, Part-II, Part-III, Part-IV