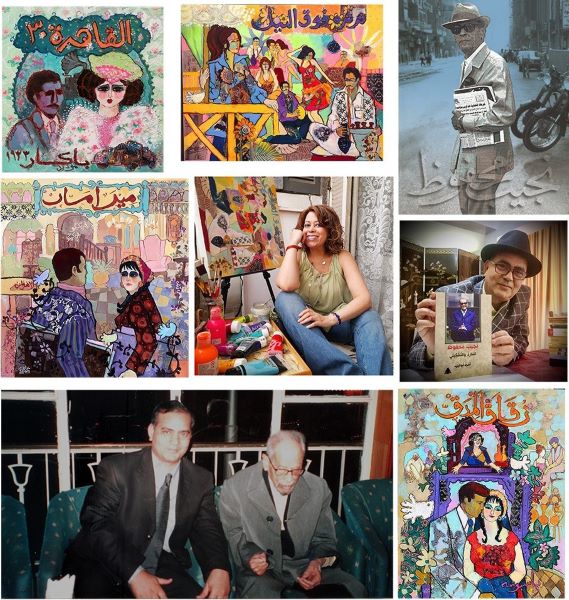

In Sally El-Zeiny’s recent exhibition, the literature of Naguib Mahfouz occupied a distinguished place

By Ashraf Aboul-Yazid

Sally El-Zeiny has strengthened the image of the painter woman in the Egyptian and Arab arenas. Her works have such an imprint that one does not search for her signature in order to know that the painting is hers, as it presents the spirit of joy with its explicit colors and implicit symbols.

I interviewed her about her message in art, and her most recent exhibition, in which the literature of Naguib Mahfouz occupied a distinguished place, among the scenes she chose to summarize a historical period in the paintings of the exhibition, which came as an “extended” artistic project (2018-2022), dealing with “The Literature of the Sixties,” as that formed The very dreamy period – from her point of view – was fertile and inspiring material that presented Egypt in a civilized, aesthetic and revolutionary manner that characterized that period of the fifth and sixth decades of the twentieth century.

The Nasserist Experience

Egypt was affected by the revolution in all sectors, and its influence was similarly evident in Egyptian narrative cinema, through a contemporary vision of the “master scene” of the film, which is the influential scene that cannot be erased from the collective memory, or the scene that sums up the film, or that which is firmly established in the artist’s memory in particular. In paintings bearing “written texts”, the artistic project deals with the distinctive features of “literature of the sixties”, and the influence of the “Nasserist experience” – in reference to the Egyptian President Gamal Abdul-Nasser- on the literary movement in that period, where “socialism” imposed its rules on society’s behavior and organizations, reviewing the features and characteristics of cinema of the “fifties”. “sixties” is a narrative supporting the regime, coinciding with the official beginning of the public cinema sector, and that prosperous period in the history of Egyptian cinema, taken from literary works “novels” by writers of the “sixties” period of the twentieth century.

Sally El-Zeiny’s project presented visual texts parallel to those “scenes” that were engraved in the collective memory, with a special visual presentation of the highest cinematic scene, the Master Scene, and a special combination of a group of influential scenes in the film, after adding her own impressions about those scenes, which differ in their treatment from the direct form of the original cinematic scene…

The Scene

The basis of this artistic project – “The Scene” – was applied research and a solo exhibition entitled “Literature of the Sixties in Egyptian Narrative Cinema – a contemporary vision of the movie poster – The Scene” – through the exhibition (The Scene), as presented by Sally El-Zeiny:

“Our relationship with the cinematic “scene” will continue to be full of beautiful memories and feelings linking us to our past, and the “cinematic posters” with the memories and stories they carry will continue to take us back to the beautiful past, whether they are huge posters, or small hand-drawn paper advertisements that carry the spontaneity and simplicity of the time from which it came. , tools to restore the time of beautiful art, and the extent of the obsession associated with collecting these posters, as it is an intimate relationship between the film and the recipient, creating a pre-existing link between the viewer and the film before it was shown, and it is also linked to specific memories that transport us through time to an imaginary world, and events that we did not witness or lived through, so they form It is not a case of nostalgia for a past time… The literary movement during the period of the “fifties and sixties” in Egypt is considered a prominent landmark in the history of contemporary Egyptian literature, as it was imbued with special features that were greatly influenced by political events, especially after the outbreak of the revolution of July 23, 1952, and the events that followed it. It affected the social scene in Egypt in that period and after, and since many cinematic films were produced during that period, it first relied on “literary texts” produced before or during that period, in a distinctive artistic synthesis that included many elements of authorship, photography, directing and production, which were clearly influenced by that era.”

A new chapter will be added to the writer’s book (Naguib Mahfouz | The Narrator and the Artist), in its next edition.

El-Zeiny believes that the July 1952 Revolution, and the interest of the men of the revolution, led by Abdel-Nasser, had a major impact on the state’s recognition of cinema as a “cultural industry,” and especially an “indicative” one. This was embodied in the issuance of cinematic legislation with laws aimed at rationalizing the service of this industry. It happened through several measures, the most important of which was “nationalization”, which began at the beginning of the sixties, when cinema in Egypt was nationalized so that its large sectors and studios became the property of the state, in what was called “the sector”, just as it was nationalized in all other economic and industrial fields in Egypt, and it was nationalizing cinema and practicing its production through public sector management has both positive and negative consequences.

As for “The Scene,” it is an extended artistic project submitted for evaluation at the Faculty of Fine Arts in 2018. El-Zeiny continued working on it until 2022, highlighting an important period in the history of the Egyptian cinema, in which distinguished models of writers emerged that were classified as “literature of the sixties.”

The Revolutionary Cinema

With the distinctive features that this literature carries, and its influence on the political events and economic and social life in Egypt in that period, then the extent to which this was reflected on the “cinema industry”, or what might be called “revolutionary cinema”, since that era was one of the fruitful and wealthy years, which some of them are among the classics of the golden age of Egyptian cinema, then studying the distinctive artistic style of making the movie poster in the sixties of the last century; trying to produce artistic works based on the “scene” or what was called the “Master Scene”, which is the influential, unforgettable, or never- erased from the collective memory, the memory of the recipient, or the scene that sums up the film.

The artist also tried to come up with new visual treatments in producing visual works and graphic designs for the posters, based on what was stored in the collective memory of the recipient, or perhaps that which was deeply rooted. In her mind, it is a “special vision” based on that scene, and highlighting examples of those films, which carried a deep social vision that reflected the political trends of that era.

El-Zainy notes that the “sixties” generation represents an important episode in the history of creative literary production on both the Egyptian and Arab levels.

The 1952 Revolution also helped in the emergence of modernity in all arts. The July Revolution may have imposed its sovereignty over political life, but it allowed literary works to be published with some freedom. The awareness of the generation of the sixties was opened to the July Revolution, and it was mature in a way that enabled it to be more understanding and dealing with the events, as Abdel-Nasser began to take control of matters with strong fists and began to reshape reality with its economic and political aspects.

This period lasted until the end of the fifties and the beginning of the sixties, in which many of the dreams of this generation were fulfilled. The conflicts and defeat of that period were also strongly reflected in the writings of that generation, as they appeared in their works. For example, in “Naguib Mahfouz,” starting with “The Thief and the Dogs,” and ending with “Miramar,” which appeared before the setback in two months.

El-Zainy sums up by saying that the sixties witnessed the most brilliant processes of political and cultural construction, which coincided with the birth of real revolutions and major victories. It also witnessed the horrific catastrophe of setbacks, a time when Arab nationalism was at the height of its prosperity:

“The writers of the sixties, including Mahfouz, were innovators. They brought about an important shift in the history of Arabic writing. They were a natural product of the emerging political ideologies that the region was rife with at that time. The generation of the sixties grew up in Egypt during a period of nationalist and Arab expansion, in which Egypt was influential.”

On the course of things in the Arab world, and hence, when talking about the experience of the generation of the sixties, it is not possible to ignore the impact of the “Nasserist experience” on them, on their formation, on their ideas, and on their future later as well.

The most important feature of the writing of the generation of the sixties is the great “interest in social depth.” That vision that was prevalent in the writings of Mahfouz, Taha Hussein, Al-Aqqad and others, also that deep critical spirit that distinguishes the writings of this generation, the future vision, and the language that is no longer merely a narrative and aesthetic language in the ordinary sense, and the narrative structure. It differs from one person to another. Rather, there have become multiple, new and different structures, as this literature has been translated into all European languages, such as the writings of Mahfouz, for example, which reveals its importance, which is no less than the importance of world literature in its aesthetic level.”

The Art We Want

El-Zainy refers to the statement of August 8, 1952, issued by Mohamed Naguib, the 1st President of the Republic, to filmmakers, entitled “The Art We Want,” which stated:

“Cinema is a means of education and entertainment, and we must realize that, because if we misuse it, we will bring ourselves to the bottom and push the youth into the abyss.”

This was the first statement of the first man of that era, indicating awareness, and his conviction that Cinema has its place at the top of the regime. This awareness of the importance of cinema, which was raised early in the life of the revolution, heralded a clear and specific vision of the path of cinema under the new era, and the possibility of resorting to it as a tool of the regime.

Films of the 1950s discussed the Egyptian political and economic reality before and during the July 1952 Revolution, and the limited margin of freedom that was available to filmmakers in that period. These films were also linked to Egyptian social reality and its problems, and their criticism was harsh, reflecting “the principles of the revolution adopted by the regime.”

That period witnessed a remarkable creative movement, says Sally El-Zeiny. In 1960 AD, the film “A Beginning and an End” was shown as the first literary work by Naguib Mahfouz, and in 1961, as socialist decisions were issued according to which many aspects of economic activity were transferred to the state, including some activities.

In 1962, the film “The Thief and the Dogs,” based on the novel by Naguib Mahfouz and directed by Kamal Al-Sheikh, was nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. In 1966, Salah Abu Saif presented the film “Cairo 30” based on Naguib Mahfouz’s novel entitled “New Cairo”, which was nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and the film “Khan Al-Khalili” by the same writer, and in the wake of the defeat of the Arabs in June 1967 and the announcement of Abdel Nasser stepped down, and after his return after the demonstrations of June 9 and 10, the public sector presented 20 films, equivalent to 60 percent of the annual production.

At the beginning of the sixties, Egypt went through a period of social transformation, where “socialism” imposed its rules on society’s behavior and organizations, and this naturally included “Egyptian cinema.”

Egyptian cinema became “realistic” since the State entered the field of competition in production, and returned to its old customs after reform. It was the same under the public sector, as it was a unique experience that lasted from 1963 until 1969. The presence of this exceptional leadership, represented by Gamal Abdel-Nasser, on the Egyptian political scene from the fifties until the end of the sixties was a contributing factor to the emergence and confirmation of a special cinematic trend whose roots grew with the first years of the revolution, and its presence was confirmed in the sixties as a dominant trend, which is “fear” cinema.

Cinema sought to distance itself from the present with its dangers and resorted to the past for protection and security from the consequences of colliding with that present. Thus, the current Egyptian reality became absent from Egyptian cinema, as it refers to anti-democratic practices imposed by the regime, represented by one party.

Sally El-Zeiny classifies the films of the sixties onto the present: represented by the films: Cairo 30, The Man Who Lost His Shadow, and The Earth, and films of the revolutionary present that adopt its ideas: represented by: A Man is in Our House, Sunset and Sunrise, The Open Door, The Thief and the Dogs, and “The Quail and Autumn”.

(The Scene) exhibition presented twenty artworks in the period from 2018 to 2022 using the mixed media technique on a stretched canvas, which represented visual texts parallel to the scenes engraved in memory, with a new plastic presentation of the highest cinematic scene, or with a special combination and combined combination.

From a group of influential scenes in the film, accompanied by written texts bearing the name of the film with a special plastic vision, after adding her own impressions about those scenes, which differ in their treatment from the direct form of the original cinematic scene presented on the cinema screen in its entirety in black and white, to give her own color character to the film. The scene, as she imagined it, is full of imagination, colors and dimensions, with a special and different visual display.

We will choose her vision of the selected archival scenes, from works inspired by the novels of the writer Naguib Mahfouz, the first Egyptian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, and whose events all take place in Egypt, and in which a recurring theme appears, which is “the Egyptian neighborhood,” and his literature is classified as “Mahfouz.” “Realistic literature and he is one of the most prominent writers whose works have been transferred to cinema and television.

The name Naguib Mahfouz appeared on the cinema screen in 62 Egyptian films in the period from 1947 to 1989, from “The Avenger” directed by Salah Abu Seif to “Heart of the Night” directed by Atef Al-Tayeb. These films are divided into 6 groups according to the role of the writer in each film, and these groups are: screenwriting (14 films), story and screenplay writing (3 films), unpublished cinematic story writing (8 films), films based on the writer’s novels (27 films), films made based on the writer’s short stories (9 films).

Mahfouz has published 34 novels since 1939, and 20 novels have been prepared in 27 films since 1960, which are: New Cairo 1945, Cairo 30 – 1966 / Khan Al-Khalili 1946, the film 1966 / Midaq Alley 1947, the film 1963 / The Mirage 1948, the film 1970 / A Beginning and an End of 1949, the film 1960 / Between the two palaces 1949, 1964 the film / Qasr Al-Shouq 1957-1967 / Al-Sukkaria 1957-1973 / The Thief and the Dogs 1961-1963 / The Quail and the Autumn 1962-1968 / The Road 1964-1965 / The Beggar 1965 – Al-Shahat 1973/ Gossip above Nile 1966-1971/ Miramar 1967-1969.

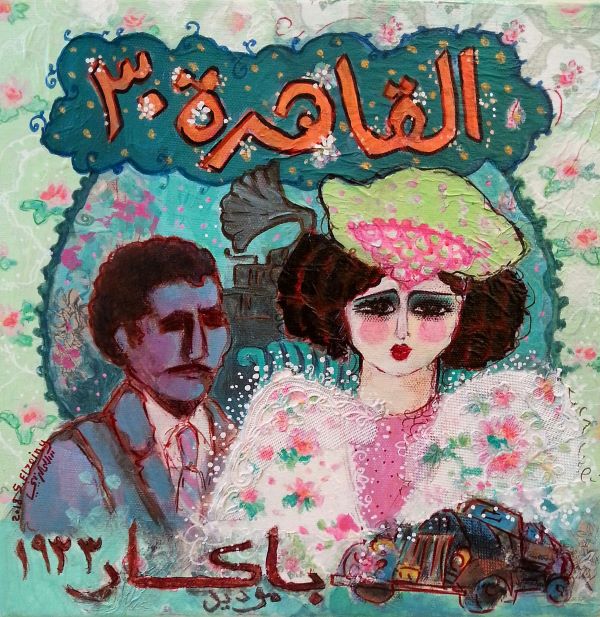

Cairo 30

Sally El-Zeiny’s first work that is inspired by the literature of Naguib Mahfouz “Cairo 30”, measuring 30 x 30 cm without a frame, using the Mixed Media technique on stretched canvas, using acrylic paints, waterproof colored pencils and a collage of (wrapping papers – patterned tissue paper – patterned linoleum – transparent white glue). ), December 2018.

The novel was first shown as a cinematic film entitled “Cairo 30” on October 31, 1966, based on the novel “New Cairo”, with a screenplay by Salah Abu Saif, Ali Al-Zorqani, Wafiyya Khairy, dialogue by Lotfi Al-Khouly, and starring Souad Hosni, Ahmed Mazhar, Hamdi Ahmed, Abdel Aziz Makaiwi. , Shafiq Nour El-Din, Tawfiq Al-Deqen, Ahmed Tawfiq, Aqeela Ratib, and Naima Al-Saghir, photographed by Mohsen Nasr, scene design by Maher Abdel Nour, produced by Nahhas Studio, and directed by Salah Abu Seif.

The artwork conveys Naguib Mahfouz’s expression of the political and social turmoil in Egypt in the period between the two world wars, through 4 characters representing the different trends in society: “Ali Taha,” who believes in science, “Mamoun Radwan,” his religious opposite, “Ahmed Badir”, who surrenders to reality, then Mahjoub Abdel Dayem, the petty bourgeois opportunist, who takes revenge on poverty by destroying all values and morals.

The four characters interacted in the Philosophy Department at Cairo University, which is the focus of political and intellectual activity in Egypt after the 1919 revolution.

In this work, the artist relied on that sad dramatic scene, which in her point of view represents the pinnacle of tragedy, with “Ihsan” accepting marriage to “Mahjoub,” whom she hated and despised, at the time of her love affair with “Ali Taha,” and the harsh circumstances called her to accept him as a facade husband. A socialite hides her sinful relationship with His Excellency Minister Qasim Bey. With this miserable marriage, she ends all her aspirations and dreams of love and “commits suicide in silence.” While she sits on the balcony listening to the song “Mohamed Abdel Wahab” through the gramophone, “Mahjoub” follows her. Trying to justify his opportunism and his shameful role as a rented husband, at the bottom of the painting comes the huge advertisement for the luxury car, “Paccar Model 33”, which accompanied the dialogues of “Ihsan” and “Ali Taha” about the miserable society and its degrading class, declaring the victory of greed and the power of capitalism.

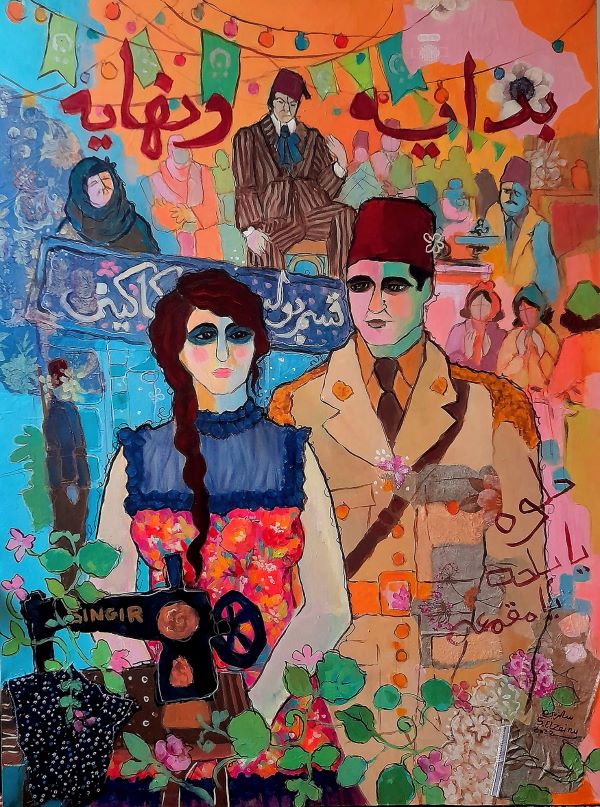

A Beginning and an End

As for the artwork “A Beginning and an End”, 100 x 75 cm, it came without a frame, and with the same technology and materials, produced in December 2022.

The novel was shown as a cinematic film entitled “The Beginning and the End” in 1960, based on Mahfouz’s novel published in 1949, with a screenplay by Salah Ezz El-Din, starring Farid Shawqi, Omar Sharif, Amina Rizk, and Sanaa Jamil, filmed by Kamal Karim, produced by Dinar Film, and directed by Salah Abu Seif.

The film was nominated for the Moscow International Film Festival award in 1961. The artist Sanaa Jamil also won third place as the best international actress for her role in the film, and the film was ranked seventh as the best film in the history of Egyptian cinema.

In the artistic work, the artist Sally El-Zeiny shows how Naguib Mahfouz expressed the state of extreme poverty that a large family suffers from after the death of its breadwinner, with the eldest son, Hassan, forced to work as a singer, a thug, and an opium dealer to help the family and Nafisa goes – missing her beauty – to the path of vice after being let down by “Suleiman,” the grocer, where she continues to devote herself and work as a seamstress to cover the family’s expenses, and satisfy her brother Hassanein’s hunger, his class aspirations, and his opportunism to gain access at the expense of all the family members.

The black sewing machine came at the top of the center of the painting, surrounded by climbing ivy branches, to meet with the opportunist “Hassanin” then ended with his look at Nafisa, who appeared in a dress with an exposed chest of black chiffon, while her eyes were darkened with black mixed with tears of oppression and sadness, covering her face with layers of vulgar powder like a prostitute, while in the background of the painting appeared a sign for the “Sakakini Police Department” where she was summoned Hassanein to bail her out, while a group of women appeared with the crocodile singing in sarcasm, as a folk song sentence was printed on Hassanein’s military jacket: “Sweet, balha, oh oppressive.”

And at the top of the work, Suleiman the scoundrel, the grocer, appears watching, while “Hassan” continues his frivolous life of celebrating weddings, and “Hassan’s mother” surrenders. “The mother of all beings, crushed by poverty and disease, has no help.”

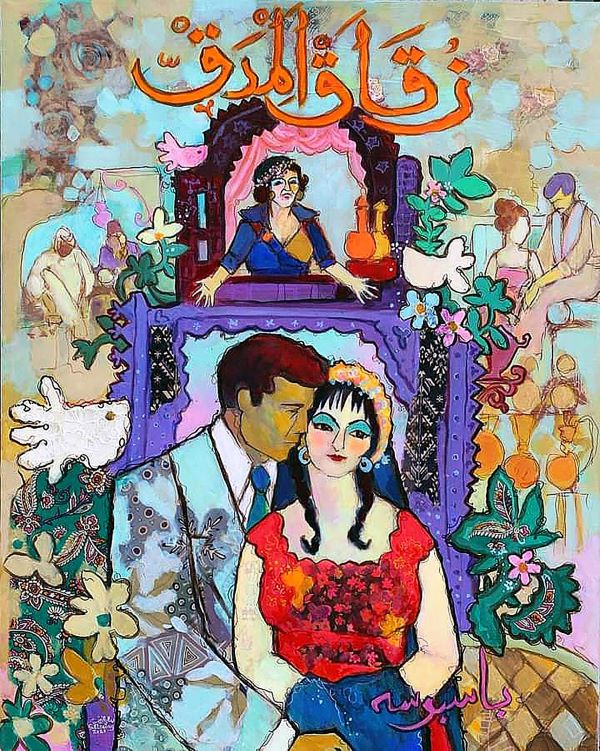

Al-Madaq Alley

The third archived scene, “Al-Madaq Alley”, 70 x 90 cm without frame, with the same technique and materials, December 2021. The novel was presented as a cinematic film entitled “Madak Alley” in 1963 based on a novel of the same name that was published in 1947, with a screenplay by Saad El-Din Wahba, starring Shadia, Salah Kabil, Youssef Shaaban, and Aqeela Ratib, produced by Ramses Naguib, and directed by Hassan Al-Imam.

In the artwork, the lover, “Abbas,” takes the center stage of the painting, embracing “Hamida,” who has rigid features, of an orphan girl who aspires to wealth, while she wears her black sheet to cover that tattered patchwork dress. In the foreground is the word “Basbousa” as pronounced by “Hamida,” so that the two meanings “Bas” – which means giving a kiss – blend together – “Kiss” and “Basbousa”.

The artist placed the two lovers inside a frame inspired by the distinctive “mashrabiya” of the ancient alley in a random geometric building topped with the window of the house of Hamida’s mother. She is calling for her daughter after she fled after being seduced by “Faraj”, her pimp, as it appears in the background.

Working with a tray of basbousa (a sweet cake), while the people of the neighborhood sit in the background of the artwork, and the branches of the plants, the white doves, and the flowering background continue to suggest Hamida’s pink aspirations and dreams for an easy life of extravagance for which she paid with her life at the end of the novel…

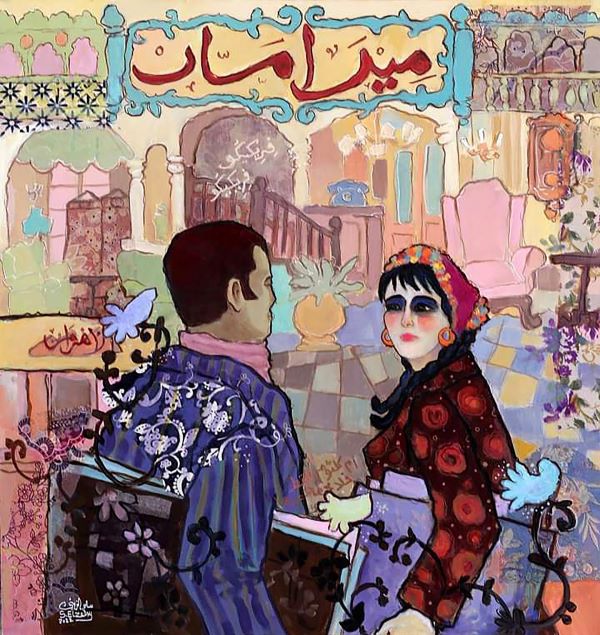

Miramar

As for the artwork “Miramar”, 85 x 80 cm without a frame, with the same technology and materials, 2022. It comes as a scene from the 1969 film “Miramar,” based on a novel of the same name that was published in 1967, with a screenplay by Mamdouh Al-Laithi, starring Shadia, Youssef Shaaban, Imad Hamdi, and Abdel Moneim Ibrahim, and directed by Kamal Al-Sheikh.

In the artwork, the distinctive decoration of the “Miramar” Pension in Alexandria is at the heart of the work, as the dusty and antique color palette dominates the elements of the painting. The artist also paid attention to the details of the interior decoration and furniture because of their essential role, as most of the events take place inside the old pension, and she collected the elements of the interior decoration.

The exterior façade of the pension has an artistic conception of its own, as the pension sign appears in a deliberate decorative manner above the painting, and the details of the scene are as mentioned in the film (the chandelier, the antique clock, the caravan, the wooden staircase, the marble floors), and the “word Frequeko” that “Hosni” repeats.

Allam is the wealthy, frivolous young man, while Zahra, is the central character, the dreamy, ambitious rural girl, depicted in the center of the painting, looking back, perhaps with some arrogance and condescension, at Mahmoud Abu Al-Abbas, the simple newspaper seller who does not satisfy her overwhelming ambition for city life, carrying newspapers and in the background. The Al-Ahram newspaper logo appeared on the newspaper stand, and artist Sally El-Zeiny – as usual – linked the two human elements with a tuft of flowers and birds, as she is always present to link men and women in her works.

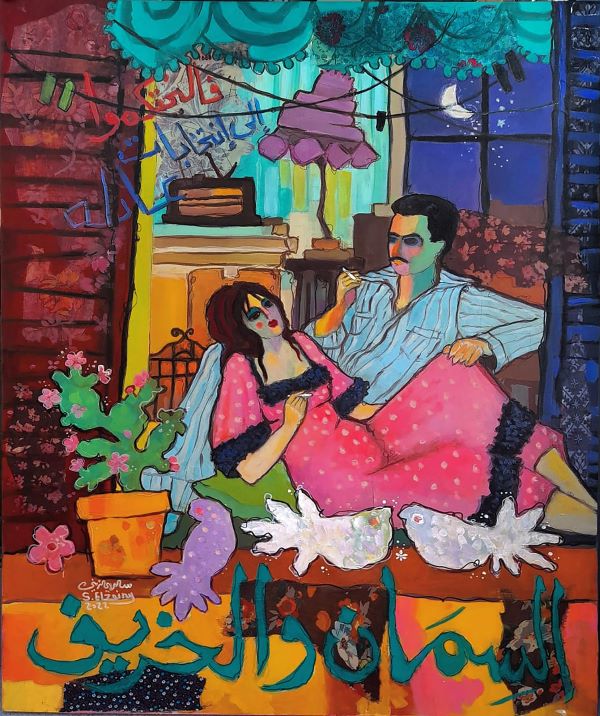

The Quail and the Autumn

In her work “The Quail and the Autumn”, 70 x 90 cm without a frame, the artist chooses the same technique and materials in her painting, which she completed in 2022.

The novel was shown as a film entitled “The Quail and the Autumn” in 1967, based on Naguib Mahfouz’s novel “The Quail and the Autumn”, which was published in 1962. The film stars Nadia Lutfi, Mahmoud Morsi, and Abdullah Ghaith, produced by Ramses Naguib, and directed by Hossam El Din Mustafa.

Regarding the artwork, we read in Sally El-Zeiny’s report:

“You see the sea enchanted by “October,” so you fall into daydreams. You also see flocks of quail collapsing to an inevitable fate, after an arduous journey full of imaginary heroism.

Cairo now is a memory. Covered with sadness… Loneliness is a bitter experience, but it is necessary to avoid looking at the faces that cause anxiety and restlessness, and the sights of glory that incite heartbreak…

Try loneliness and the companions of loneliness… the radio, the book, and dreams….” the quails and the autumn of Naguib Mahfouz 1962.

“Issa Al-Dabbagh” flees to Alexandria after being dismissed from his job and obsessed with profiteering and bribery. He meets the prostitute “Riri” with whom he lives a frivolous life without the slightest responsibility or burdens. “Issa”, the old revolutionary, falters between his principles and riding the wave of Machiavellianism and justifies his quick means of profit. Then he continues the path to indulge in vice. His relationship with the prostitute represents in the novel the climax of his downfall, but at the same time it heralds a new beginning.

In this work, Sally El-Zeiny used cinematic decor for the warm, intimate scene of Issa lying on the floor while his mistress rests on his leg while they smoke in front of the fireplace on a cold Alexandrian evening… where the crescent moon appears still with the stars in the background and the fireplace radiates an orange glow that dispels the cold blue, the lampshades, the radio and the phrase “Kan” Issa raved about it under the influence of alcohol, “…let them hold fair elections…” She represents the conflict before the revolution…

She added her vision of the scene from an external perspective that reflects the balcony wall that was spread out with doves, a clothesline, and cactus pots..

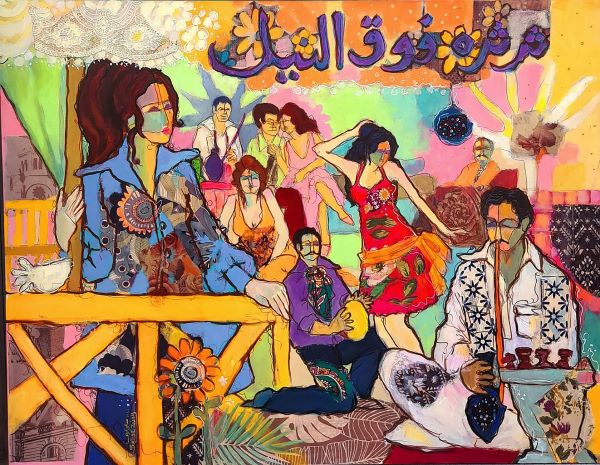

Chatter over the Nile

In “Chatter over the Nile”, 70 x 90 cm, unframed, with identical techniques and materials to this group of landscape works, Sally El-Zeiny painted this painting in December 2021.

The novel, which was published in 1966, had kept its name when it was shown as a movie entitled “Chatter over the Nile” in 1971, with a screenplay by its author Naguib Mahfouz, starring Imad Hamdy, Magda Al-Khatib, Ahmed Ramzy, Adel Adham, Neamat Mukhtar, and Mervat Amin, and produced by Ramses Naguib, and directed by Hussein Kamal.

After the military defeat in 1967, the novel presents the story of the life of a group of “unconscious” people who try to escape from the miserable daily reality, where they meet in the float of the actor “Rajab Al-Qadi”, where they live a life of futility and vent their anger and resentment over their miserable conditions with the smoke of acorns.

Mahfouz says, “He thinks himself is the center of the universe, and the acorn rotates because of him. The truth is that the acorn rotates because everything rotates, and if the spheres were moving in a straight line, the “stitch” system would change…”

In this absurd scene, the artistic work is dominated by the character of Anis Zaki, an employee of the Ministry of Health who is always unconscious due to smoking hashish, making him the half-sane, half-crazy person.

The work is holding the nut, with coal and stones in front of him, while Samara, the journalist, stands in a compound formation on the buoy ladder, looking at the scene. The absurdist is protesting, while everyone is engaged in promiscuity, amusement, and dancing in the background of the work, led by “Sana,” the reckless university student searching for fame at any cost. She is in the middle of the painting, wearing her red dress, dancing in the absurd scene, while everyone is busy with their own pleasures…

In all six of Mahfouz’s paintings, and all of the project’s paintings in general, the visual artist Sally El-Zeiny preferred to use spontaneous Arabic calligraphy, sometimes at the forefront of the scene, at the top of it, or at the bottom of the work, in a situation similar to or close to the style of cinematic posters in the sixties of the twentieth century, when they were drawn and written by hands through artists and calligraphers.

She wanted to inspire the cinematic atmosphere of the sixties and fifties with her artistic project. She also did not rely on the original features of the actors, but rather showed them with her own vision of the characters as they appeared in the literary work, and as she saw them in her imagination, while she made great use of cinematic decor, in combinations and treatments. Her own artistry through compositions of several scenes combined after she added her own vision.

The Meeting Point

The meeting point between Sally and Mahfouz is based on the connection to the locality, as the artist’s general project is based on inspiration from “folk heritage,” which came as a result of her upbringing in a popular environment in the “Shubra neighborhood,” coinciding with the happy childhood periods in her grandmother’s rural-bred house, with an architectural style.

The old stone, as well as the stories and legends that her grandmother told her when she was spending the long summer vacation in her simple house, where she fell in love with her embroidered clothes, and the clothes of rural women and women of popular areas, and this passion also quickly transferred to traditional fashion around the world, and she noticed that There is a strong connection between all of them, as they are not only warm, embroidered, intimate and sincere, but all these fashions, details and decorations are innate to humans and are distinguished by their warm colors, so in her works she relied on bright, bright and warm colors inspired by intimate folk tales and heritage, and they are also childish, honest and optimistic. .

El-Zeiny used this color palette in different variations and degrees throughout her artistic project, starting with her doctoral thesis project, “A Contemporary Vision of Al-Maqrizi’s Plans.”

In 2015, she presented her second artistic experience, “In the Garden,” which was inspired by the idea of the “garden” in contemporary modernist literature – where the paintings were An artist’s book experience inspired by modernist texts by writers and poets who dealt with “the garden” in their poetry in paintings executed on eco-friendly handmade papers recycled from “rice straw”, where bright colors were used to express gardens and flowers.

In the artist’s third project, which she presented in 2017, was the solo exhibition “Love Sonnets,” which presented a group of paintings inspired by “folklore,” represented by “folk tales of grandmothers,” where colors played a strong and pivotal role in expressing folklore, and then concluded with her exhibition.

“The Scene” 2018-2022, she dealt with the scenes as a whole in black and white, to add her own color character to the scene as she imagined it, full of imagination, colors, and dimensions, with a special and different visual presentation.

The artistic project “The Scene” received a lot of interaction and influence inside and outside Egypt, especially from the younger generations, who are decades away from the time of those works of fiction.

El-Zeiny was surprised by the promising youth at the Faculty of Applied Arts, Benha University – Department of “Ready-to-Wear Technology and Fashion” – Fourth Year, with their desire to be inspired by “the scene” in their final graduation projects, to present modern designs with an oriental spirit, by submitting fashion designs inspired by works of art and literary novels, while printing parts of the paintings in line with their fashion designs, as they designed and implemented costumes inspired by the characters of novels and artistic paintings in “the scene.”

Another celebration of the scene came in cooperation with the University of Applied Sciences – Kingdom of Bahrain – College of Arts and Sciences, in preparing an introductory lecture and visual presentation entitled “A Contemporary Vision for Cinematic Screenplay in Novel Literature in 2021/2022 as a specialized expert in the field of graphics through the university’s electronic platform to explain the artistic project “The Scene” is in preparation for its use in projects for students of the Participatory Design course, and for the students to present projects of interior architecture and decoration design that are inspired by the “Scene” paintings.

The “Scene” project also won international awards. Including the Faten Hamama International Film Festival Award, in Faten Hamama Film Festival for Best Video for the Short Promo “The Scene”, Paris May 2022, and the Jury Prize for Best Short Video – Paintings, from the Los Angeles International Independent Film Festival – September 2022.

Thus, the Mahfuzian Scenes by Sally El-Zeiny came to confirm that the inspiration of the great storyteller, in plastic works, represents a wide path that allows the passage of art, just as it prepares for the communication of generations.

_________________

[…] Also read: Sally El-Zeiny strengthens image of painter woman in Egyptian and Arab arenas […]