Bhavnani traces the ripple-effects of violence within Sindh, the role of Muhajir-Sikh hostility, and the complex face of ‘law’ that seemed to apparently support the minorities but also sometimes contributed to their misery.

Rita Kothari

Bhavnani’s prologue provides a quick snapshot of such themes, drawing from existing scholarship, but also adding details that had fallen by the wayside in previous scholarship. This sets the stage for understanding Partition. Bhavnani’s unease over the archetypal ‘proselytizing Muslim’ underlying a particular strand of history-making among Sindhi Hindus is evident in her view that:

Bin Qasim and his army did not convert the bulk of the Sindhi people by the sword. Most of Sindh’s Muslims converted gradually over the centuries, with the lower classes – the haaris or peasants, craftsmen and laborers seeking to escape the harshness of the Hindu caste hierarchy by embracing Islam. Most of these conversions were the work of missionaries, first the Syeds from Arabia, then the Ismailis, and finally, the Sufis.

While empirical observation of Sindhi Hindus shows an absence of peasants and large artisan groups, it is difficult to know for certain whether conversions did or did not happen by the sword, the enormous influence of the pirs in Sindh notwithstanding. Bhavnani’s unequivocal and unsubstantiated claim comes as a surprise early on, especially as in a subsequent discussion she mentions that apart from the restrictions that Sindhi Hindus experienced under Muslim rule, their “greatest fear… was that of forcible conversion to Islam, although this does not appear to have been very common”. Why would fear linger, if experience does not support it? And how do we understand ‘conversion’, as agency as well as imposition of change, never entirely complete, but an interstice that seeks a different narrative? Bhavnani mentions how Hindus said with contempt: “Shaikh putta Shaitan jo, na Hindu-a jo, na Musulman jo, Shaikh is the son of the devil, he belongs neither to Hindu nor to Muslim.” Were in-between identities considered diabolic, and disloyal in a society where affiliation to an authority mattered a great deal? Conversion appears as a recurring and untheorised theme, but this review is hardly the best place to resolve the conundrum that Bhavnani faces. The prologue is largely a useful lead into the book, as it interweaves pre-colonial and colonial Sindh, locating in the latter the “reversal of the power equation – with the once-restrained Hindus now enjoying power out of proportion to their small numbers, and the Muslims, who had ruled the province for centuries, now on the back foot”.

Later, Bhavnani transports us to the eve of Partition. Prior to 26 June 1947, when Sindh voted to join Pakistan, a series of events played a definitive role in interreligious relationships and economic transactions. For instance, from the establishment of colonial rule, new inequalities triggered by education and land policies arose. Some of the resentment that Sindhi Muslims felt over the increasing prosperity of Sindhi Hindus led to a demand for a Sindh region separate from the Bombay Presidency. In the 1930s and ‘40s, the communalization of politics and the rise of extreme ideological voices marked a period of immense political turmoil in urban centers like Karachi and Hyderabad. From some accounts it would appear that at Partition, many Sindhi Muslims were “exhilarated by the prospects of both independence from the British and a new social order free from Hindu domination”. Yet, Bhavnani also demonstrates how Sindh remained relatively free of communal violence for most of the Partition period.

Later, Bhavnani transports us to the eve of Partition. Prior to 26 June 1947, when Sindh voted to join Pakistan, a series of events played a definitive role in interreligious relationships and economic transactions. For instance, from the establishment of colonial rule, new inequalities triggered by education and land policies arose. Some of the resentment that Sindhi Muslims felt over the increasing prosperity of Sindhi Hindus led to a demand for a Sindh region separate from the Bombay Presidency. In the 1930s and ‘40s, the communalization of politics and the rise of extreme ideological voices marked a period of immense political turmoil in urban centers like Karachi and Hyderabad. From some accounts it would appear that at Partition, many Sindhi Muslims were “exhilarated by the prospects of both independence from the British and a new social order free from Hindu domination”. Yet, Bhavnani also demonstrates how Sindh remained relatively free of communal violence for most of the Partition period.

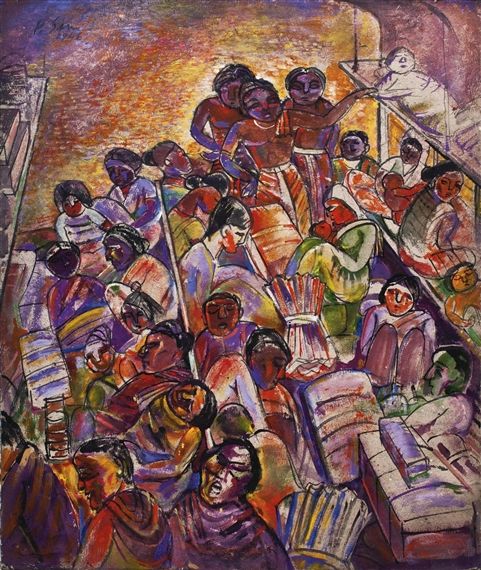

Thus, Sindh marks a significant departure from the Punjab experience of Partition in that it was relatively free of physical violence. Violence has remained central to all literary and political discussion of Partition. Print and visual narratives of Partition in India generally evoke archetypal images of mass violence and mob frenzy. A productive way of understanding violence in Sindh is to see it beyond forms of physicality – a sense of foreboding, insecurity and terror occasionally peppered with instances of stray violence. Bhavnani’s use of oral testimonies reflects the palpable sense of foreboding experienced by well-to-do urban Sindhi Hindus who felt that their self-respect, property and families could be in danger from Sindhi Muslims who resented their prosperity, or eyed their women.

Caste discrimination in a frontier region like Sindh was not as intense as in other parts of India, yet the Dalit predicament of belonging neither here nor there is evident even in Sindh. The memory of this story was triggered by Bhavnani’s section on Dalits in Sindh.

The leadership vacuum that Sindhis felt at this time would have far-reaching consequences for India: it was out of the space left hollow by the Congress that Sindhi alliances with Hindu majoritarianism grew. Bhavnani mentions that isolated acts of violence began in northern Sindh, although even then it was difficult to distinguish where criminal opportunism targeted at rich Sindhi Hindus ended and violence driven by religious differences began. The continued attacks and abductions of rich Hindus in present-day Sindh evoke similar ambiguity today. Meanwhile, Bhavnani traces the ripple-effects of violence within Sindh, the role of Muhajir-Sikh hostility, and the complex face of ‘law’ that seemed to apparently support the minorities but also sometimes contributed to their misery. In fact, memories and archives on both sides of the border show a similar ambiguity of the Pakistani and Indian states – the police and other law enforcers were involved in spurring violence, and sometimes controlling it.

Inclusive citizenship?

In a moving and political short story called ‘Boycott’ (by Gordhan Bharti, in Unbordered Memories, ed. Rita Kothari, 2009), we are told that the small village of Aarazi in Northern Sindh shrank following the migration of Hindus during Partition. However, about 20 Hindu trader families did not migrate, maintaining a stronghold on business in the village. The self-professed custodians of the Islamic nation, alongside Sindh’s traditional feudal lords, manipulate a Dalit Koli named Jaman into starting a shop and taking business away from the Hindus, so that the Hindus would leave – in effect, a boycott of Hindus. The story recounts the unfolding of Jaman’s exploitation and inadvertent participation in an agenda that he had nothing to do with. He was not a rich Hindu, nor a powerful Sindhi Muslim reaping benefits of the newly formed Islamic nation. A poor, low-caste man, Jaman was a pariah to both Hindus and Muslims. Terrorized by the feudal lords, he starts a sweet shop like the Hindus, but fails miserably at running a business. He loses money, and upon asking to be repaid, he is laughed out of court, physically thrown out, boycotted from the house of the wadero (feudal lord). The term ‘boycott’ – which Jaman thought was used for Sindhi Hindus – was now applicable to him. It occurs to him that while the term and its target Sindhi Hindus were new, as a Dalit he was never included in the idea of Pakistan, so that in a sense his being ostracized preceded the Hindu and Muslim differences. This is important to remember because caste discrimination in a frontier region like Sindh was not as intense as in other parts of India, yet the Dalit predicament of belonging neither here nor there is evident even in Sindh. The memory of this story was triggered by Bhavnani’s section on Dalits in Sindh. (Continues)

_________________

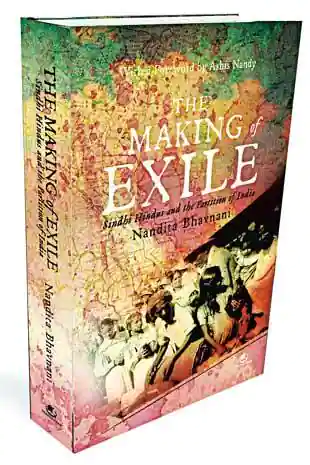

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Courtesy: Himal Mag