Around 200,000 Dalits lived in Sindh in 1947-48, although subsequent years have seen significant migration in the Thar Parkar region of Sindh. A view that Dalits would be treated better by Muslims in Pakistan than by caste Hindus in India took hold of a section of the Dalit leadership at the time of Partition. However, the living conditions of Dalits did not reflect – nor do they today – any signs of inclusive citizenship.

Rita Kothari

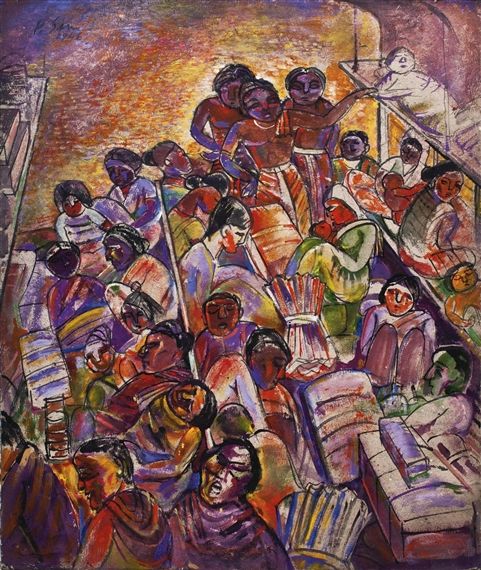

Although Partition experience of the Dalits finds place in Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence (2000), and subsequently other scholars like Ravinder Kaur have addressed it, Partition scholarship particular to Sindh has addressed the Dalit predicament in Suchitra Balasubramanyam’s pioneering essay, ‘Partition and Gujarat: The Tangled Web of Religious, Caste, Community and Gender Identities’ (2011). Bhavnani’s research breathes more life into this area of study, and demonstrates the poignancy of the ambivalent social citizenship of Dalits, who fully belonged neither to Pakistan nor India. Bhavnani informs us that by some estimates, around 200,000 Dalits lived in Sindh in 1947-48, although subsequent years have seen significant migration in the Thar Parkar region in Sindh, Pakistan. A view that Dalits would be treated better by Muslims in Pakistan than by caste Hindus in India took hold of a section of the Dalit leadership at the time of Partition. However, the living conditions of Dalits did not reflect – nor do they today – any signs of inclusive citizenship. Fearing the loss of ‘essential services’ when Dalits began migrating to India, the Pakistan government patrolled Dalit movement and prohibited their departure. Indian refugee networks, on the other hand, reduced them to sweepers and cleaners in the service of rich Sindhi Hindus.

Similar concern for such liminal spaces and Partition are reflected in Bhavnani’s section on the Sikhs, especially the Labana Sikhs, who generally hail from a poor strata of society, making a living from manual and agricultural labor. Bhavnani’s twin sections on Dalits and Sikhs are an important intervention in Partition scholarship, as they help expand the strait-jacketed, binary opposition of ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ perspectives on Partition. They also illuminate how suffering and the legitimacy of dignity – two recurring themes of Partition – carried different meanings and intensity for the minorities. Bhavnani concludes that by the middle of June 1948, one million Hindus had been able to migrate to India, while 400,000 more remained in Sindh. It must be noted that migration from Sindh has continued even to this day. In 2014, newspapers in Gujarat reported that “a Sindhi couple hailing from Pakistan” was arrested for overstaying and forging papers to buy property and “prove their Indian citizenship”. The business of Partition is unfinished as far as Sindhi Hindus are concerned. Yet there is one part of the story that took a different, sometimes more painful, form: when Sindhi Hindus arrived in India.

Similar concern for such liminal spaces and Partition are reflected in Bhavnani’s section on the Sikhs, especially the Labana Sikhs, who generally hail from a poor strata of society, making a living from manual and agricultural labor. Bhavnani’s twin sections on Dalits and Sikhs are an important intervention in Partition scholarship, as they help expand the strait-jacketed, binary opposition of ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ perspectives on Partition. They also illuminate how suffering and the legitimacy of dignity – two recurring themes of Partition – carried different meanings and intensity for the minorities. Bhavnani concludes that by the middle of June 1948, one million Hindus had been able to migrate to India, while 400,000 more remained in Sindh. It must be noted that migration from Sindh has continued even to this day. In 2014, newspapers in Gujarat reported that “a Sindhi couple hailing from Pakistan” was arrested for overstaying and forging papers to buy property and “prove their Indian citizenship”. The business of Partition is unfinished as far as Sindhi Hindus are concerned. Yet there is one part of the story that took a different, sometimes more painful, form: when Sindhi Hindus arrived in India.

Unlike Punjabis and Bengalis, Sindhis were not coming to ‘their’ state, but were unwanted, bewildered immigrants throughout India.

Bhavnani’s discussion on the vicissitudes of arrival of Sindhi Hindus in India sparked a memory of another episode, from the highly-acclaimed 1973 film Garam Hawa, by M S Sathyu. Garam Hawa is based on the life of Muslims after Partition in Lucknow. The Muslim protagonist Mirza – battling suspicion and distrust extended to him by moneylenders and banks – finds it difficult to conduct business in a society that suddenly considers him an outsider. While this forms the main thread, a related sub plot is also relevant to the present discussion. Lucknow experiences an influx of Sindhi Hindus. A Sindhi businessman rises to prosperity while Mirza loses ground to him. This interaction and competing claims made by exiled citizens and refugees changed the social and economic contours of certain cities in India and Pakistan. Bhavnani shows the competing claims over property and city spaces in both India and Pakistan after 1947. The rise of the Sindhi refugee to prosperity is particularly significant. A combination of perseverance, inventiveness and, at times, compromised ethics took Sindhis to new levels of enterprise and success after Partition. The rise of cottage industries such as making papads, pickles, pen tubes, bottle caps and so on in Ulhasnagar (Maharashtra); the inventive entrepreneurial (what would be called jugaadu in colloquial language today) duplication of ‘foreign’ labels; of subletting pavements and renting railway passes – all of these form a part of Sindhi lore, repeated by the community and sometimes by others, with grudging admiration.

This metanarrative, however true, masks the trials that a well-heeled community suffered by having to start again while dispersed across different states in India. Unlike Punjabis and Bengalis, Sindhis were not coming to ‘their’ state, but were unwanted, bewildered immigrants throughout India. Bhavnani points to the changing demography and Sindhi landscape in places such as Bombay, Kutch and Rajasthan, the competing self-definition and descriptions of labels such as sharnarthi (refugee) and purusharthi (hard-working, effort-making) that Sindhis battled with. The question of whether Sindhis were refugees – homeless people at the mercy of a host population and refugee officers – or rightful citizens of a newly created nation persisted all the way through the 1950s and ‘60s, as they struggled for homes and loans. When some dust had settled and initial survival needs had been taken care of, Sindhis also struggled for cultural recognition. For instance, there was a campaign to include Sindhi as one of the official languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

Bhavnani demonstrates how, in settling into their new circumstances, rich landowners often became shopkeepers, and educated people unused to business tried their hands at buying and selling things. Bhavnani mentions how Partition blurred the once-clear distinction between those who did business overseas (such as the Bhaibands), and the educated elite who worked in Muslim courts, and then the British administration (such as the Amils). The demands of survival did not allow the luxury of considering what type of livelihood suited one’s traditional status and skill. And yet what remained more or less constant among Sindhi Hindus in different states was sheer aversion to labor, a historical phenomenon evident in idioms such as naukri aa tokri (to serve somebody is to carry excreta).

Disavowing the past

Partition blurred many other distinctions between right and wrong, giving rise to a perception shared by some Gujaratis: “Saalo Sindhi game te karshe, the bloody Sindhi wouldn’t stop at anything.” Whether such stereotypes are justified, and how Sindhis internalize or rationalize them, would be difficult to establish. However, the negative perceptions of Sindhi Hindus (not entirely absent in pre-Partition Sindh) has affected Sindhi self-perception in profound ways. This may have some parallels across the border in the Mohajjir experience: for instance, Qurrutalain Hyder’s novella ‘The Housing Society’ (in Seasons of Betrayal, 1999; originally 1963), hints at a similar blurring of social and ethical boundaries among those who attempted a hasty economic mobility in the post-Partition period. (Continues)

________________

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Nandita Bhavnani, an independent scholar, who was raised as a typical south Mumbai elitist kid and couldn’t read, write or fluently speak in her mother tongue, became a Sindhi historian by choice. She learnt the Persian script and worked with social anthropologist Ashis Nandy for research on “Partition Psychosis”. She has travelled many times to Pakistan to explore Sindhi culture there and her research from both sides of the border has been documented in books and articles.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Rita Kothari is Professor of English at Ashoka University, Delhi. She is one of India’s most distinguished translation scholars and has translated major literary works into English. Rita has worked extensively on borders and communities; Partition and identity especially in the western region of India. She is the author of many books and articles on the Sindhi community.

Courtesy: Himal Mag