The Devanagari script will give Indian Sindhi a renewed life and return it to the fold of Indo-Aryan languages, which it had been severed from under the influence of Arabic.

C J Daswani Sindhi

According to the Indian Census of 2001, there are over thirty-one lakh mother-tongue speakers of Sindhi in India. An unofficial estimate of the number of Sindhi speakers in India is almost double the official figure. It is well-known that a large number of ethnic Sindhis in India do not declare Sindhi as their mother tongue. In the absence of a Sindhi speaking region, Sindhis are scattered all over the country and learn to communicate with their local interlocutors in languages other than Sindhi. Whatever the actual number of Sindhi speakers, a very small number of Sindhis in India receive education through the medium of Sindhi. Although Sindhi is a recognized national languages, it is taught in very few schools in the country. Over the years, since 1947, Sindhi has become largely a spoken language. All attempts at enthusing native Sindhis to learn to read and write their language have been unsuccessful. The primary reason for this situation appears to be the script in which Sindhi is written. This paper examines the question of the survival of the Sindhi language in India and critically evaluates the role of the choice of script in this struggle for survival.

Introduction

When India was divided in 1947, the Hindu refugees from the Pakistani Punjab and Bengal migrated largely to the Indian half of Punjab and Bengal respectively where they encountered a homogeneous culture and language. The existence in India of geographic regions where the Panjabi and Bengali languages were spoken as native languages contributed significantly to the emotional and cultural rehabilitation of these linguistic groups. The fate of the Sindhi refugees, on the other hand, was quite different from that of the Panjabi and Bengali refugees, mainly because there was no geographical region in India where Sindhi culture and language had an independent existence. Consequently, the Sindhi refugees scattered almost all over India and although, in the process, a number of pockets of refugee settlements came up, especially in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, the Sindhi refugees found themselves in the midst of non-Sindhi speaking majority populations. This factor of being dispersed over the entire country has contributed to a number of problems for the Sindhi migrants, including that of the script for the Sindhi language.

The Struggle

After the Partition, over twelve lakh Sindhi Hindus migrated from Sindh to India. The compulsion to migrate was an intuitive action, necessitated by incomprehension of what had happened, confusion about their plight, and despair. Starting in September-October 1947, the unending exodus lasted for over two years. And the process of migrating to India continued for decades; and continues even today with a continuous trickle of Sindhi Hindus crossing over into India.

In the initial period, many families did not know where they were going and what the future held for them, but they felt they had to leave the land of their ancestors. People traveled by road, rail and sea, some even by air. They traveled in large groups, often in clusters of neighborhoods (Thakur, 1959); for they felt there was safety in numbers. Once in India, they encountered a host of problems: there was no Sindhi speaking region or province where they could settle as a homogeneous group. Most families had to struggle to find avenues of livelihood. Initially, most families were accommodated in ‘Refugee Camps’ set up by the provincial and federal governments. Many families moved from one refugee settlement to another, in search of work, to look for lost relatives, or in the hope that the grass on the other side would be greener! And yet, the despair was replaced by strength, courage and determination to reverse the tragedy that fate had doled out to them.

The struggle that the Sindhi community in India had to face is well known and recorded in numerous documents and literary works. The purpose of the present paper is not to recount the hardships, the struggle and the turmoil that the Sindhi community faced in the early days in India. It goes to the credit of the community as a whole that they did not submit meekly to the cruel fate. Like the mythical phoenix, the community rose from the ruins of physical displacement and economic penury to build a new life in their new adopted homes. It is well known that in those early days no Sindhi was ever seen to beg or ask for charity! In place of loss of motherland Sindh, in India the community found solace within a larger cultural milieu.

Even as the community was finding new opportunities for work, many individuals and groups were engaged in social, cultural, educational and spiritual rehabilitation of the community. Although the community had to contend with reconciling themselves to the changed conditions of social and educational dispensation in local Indian languages, a number of Sindhi medium schools were set up, especially where the Sindhi settlements were large. Many well-known litterateurs and thinkers, who had been established writers in Sindh, along with school teachers and college dons, devoted themselves to the intellectual and educational rehabilitation of the community.

While the larger Sindhi community in India was bravely facing the struggle to survive, the Sindhi writers, social workers and leaders were seized with a major struggle for the inclusion of the Sindhi as one of the ‘recognized’ languages in the Indian Constitution, which was adopted in 1950,. The Constituent Assembly that was drafting the Indian Constitution had failed to include Sindhi in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution where all the major Indian languages had been listed. The struggle for the inclusion of Sindhi in the Eighth Schedule took twenty years, and the language was finally included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution in 1967. (A detailed account of the ‘Movement for the Recognition of Sindhi’ is available in Daswani, 1979.)

Sindhi Script

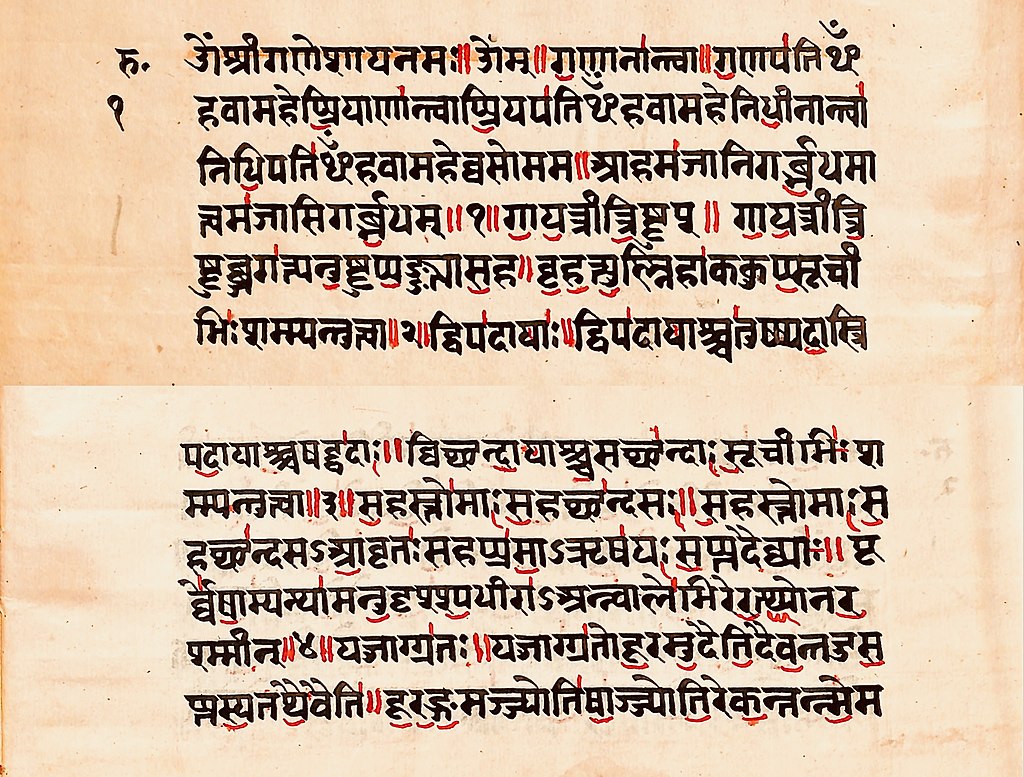

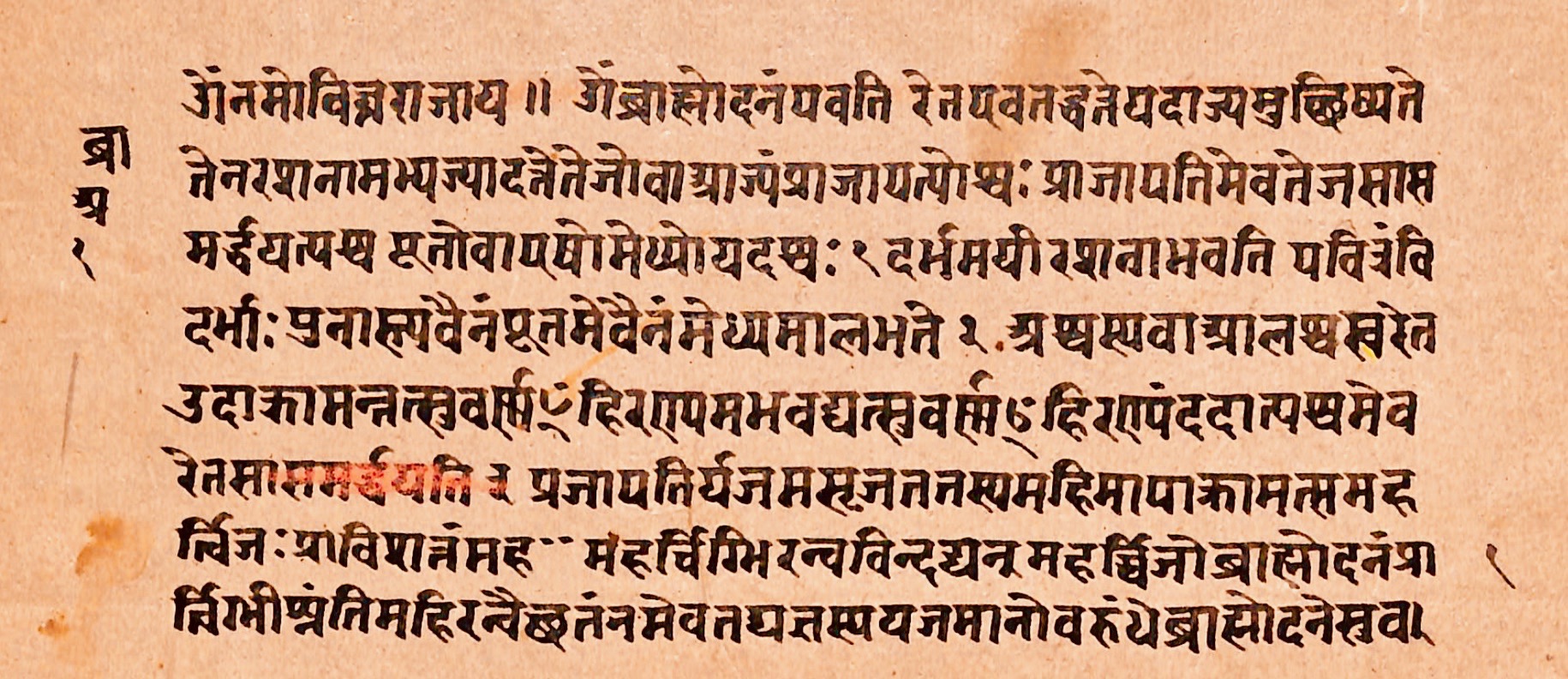

Several scholars of Sindhi, both in India and Sindh, (Jairamdas Daulatram, 1957; Khubchandani, 1969; Allana, 2002) have traced the history of the Sindhi script. There is historical and archeological evidence that Sindhi has been a written language for many centuries. Even before the Arab conquest of Sindh in 712 AD, Sindhi had a well-established writing tradition. In fact, it is claimed that even before 712 AD, Sindhi was written in more than one script.

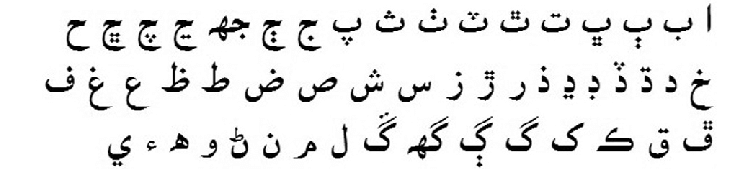

It has been shown, with impressive documentary evidence, that until the British conquest of Sindh in 1843, the Sindhi language was written in a script related to the Devanagari script (Jairamdas Daulatram, 1957). When, after the British conquest, Sindhi was made the language of administration in Sindh, the British rulers, quite arbitrarily and against the opinion of competent scholars and grammarians, imposed the Arabic script as the official script on Sindhi. The Hindu Sindhi population at that time agitated against this move, as a result of which the British government also recognized the original Sindhi (Khudawadi) script as an additional script to be taught to school children in the municipal schools in Sindh (Khubchandani, 1969).

However, within a short period of less than ninety years from 1853, when the Arabic script was made the official script of Sindhi, to 1947 when the country was partitioned, the Arabic script became increasingly popular because of the administrative favour and economic advantages flowing out of the knowledge of the Arabic script. What had been introduced as an administrative convenience came to be associated in the minds of the people as the only script for Sindhi.

Looking at the development of Sindhi language, it is clear that over the centuries, the language has always been written in more than one script. Until the imposition of an official script for political reasons by the British, Sindhi was written in several scripts. It may be noted here that even the ‘official’ script took nearly half a century to become a ‘standard’ script.

At the time of the Partition, then, the Hindu Sindhis who migrated to India could be divided into two groups: those who wrote and read their language in the Arabic script, and the others who wrote and read their language in a script other than the Arabic, viz. the Devanagari script, the Khudawadi Sindhi script, and the Gurmukhi script. Many Sindhi Hindus were literate in more than one script – Arabic, Khudawadi and Gurmukhi. (Those who had learnt English, could also employ the Roman script to write the Sindhi language.) The first group comprised those who had been through the formal school system in the major urban centres (with Sindhi as the only medium of instruction at the primary stage), and intended to make a career in the civil and administrative services. The second group comprised largely the urban Hindu business community, the rural Hindu population, the supporters of the Devanagari script for Sindhi and the Hindu women, who were taught to read and write Sindhi in the Gurmukhi script in the local gurdwaras (tikanas) (Daswani, 1985).

Script for Indian Sindhi

In India, even before the Sindhi leadership mounted the movement for the recognition of Sindhi, the community had to face the problem of the choice of a script for teaching the language in schools. As early as December 1948, several educationists, social and spiritual leaders as well as political leaders organized a meeting in Bombay where more than 200 delegates proposed that the language be written in the Devanagari script in the changed circumstances in which the community found itself in India. Historicity and appropriateness of the Devanagari script, as well as the use of this script before 1853, was cited as reasons for the change from the Arabic script. A resolution, supporting the change of script, was sent to the Government of India (GOI) and was accepted by the government in early 1949. The GOI directed all the concerned ministries and departments to effect the change. However, in July 1949, a number of head masters of Sindhi schools in Bombay appealed to the government not to change the script. After a protracted period of representations and counter-representations, in 1951, the government decreed that while the script for the language in India would be the Devanagari script, in schools where the pupils and their parents wanted to learn in the Arabic script, they could do so. The reverse ghost of the British decision in 1851-53 had risen once again!

The Arabic-Devanagari controversy was picked up by several prominent writers who had already spearheaded the demand for the recognition of the Sindhi language. The question of the changeover to the Devanagari was put on the back-burner, and the government left it to the community to decide which script they wanted for the language. Consequently, many provinces in India switched over to the Devanagari script, while some other provinces, notable Bombay (later Maharashtra), and chose the Arabic script. It is another matter that as a result of this controversy and confusion, many to the legal and financial provisions available to other Indian languages are denied to Sindhi. This was the death-knell for the Sindhi language!

Writers for Arabic Script

Distinguished and greatly respected Sindhi writers, who had migrated from Sindh and settled largely in Bombay and its suburbs, took up the cudgels for the Arabic script. All in their late twenties and early thirties, these writers continued to write in the Arabic script. It must be recalled that it was this band of writers who chronicled the early struggles of the community in their writings. It must be recognized that these writers were the most psychologically and emotionally attached to their status in Sindh, which had become only a memory. While they wrote about the Indian Sindhis, they continued to pine for Sindh and the Sindhu. For years, they wrote about their lost motherland and their belief that they would return to Sindh one day. This mindset had detrimental effect on younger and emerging writers. Influenced by their seniors, they too pined for Sindh, and although they lived in rain-soaked Bombay, they wrote about the sands of Sindh! In retrospect, it is possible to see that the senior Sindhi writers influenced everything that had anything to do with the fate of the Sindhi language in India.

One of the arguments forwarded in favour of the Arabic script by these writers was the need to ensure contact with the Sindhi litterateurs and scholars in Sindh. For many years after the Partition, there was no formal or official contact possible between the two sides. However, there was unofficial traffic of writings and ideas, as well as personal contact between the intellectuals in Sindh and the Indian Sindhi writers. It may be recalled that during this period the Sindhi language in Sindh was undergoing far-reaching changes.

Many Sindhi creative writers continued to write in the Arabic script, with the result that while they wrote about their thoughts and emotions, not many wrote for the newer generations of Sindhi learners; and in any case, whatever textual material was produced for schools could not be shared by all learners in the country because of the dual script policy and practice. Over a few decades, a vast chasm appeared between the writers and readers. Because the newer readers were unable to read the literature being produced, gradually the writers became their own readers; there being no contact between the writers and the community. With the borders between Sindh and India having become more open recently, the Indian writers have found a newer readership among the Sindhis in Sindh, and have been writing for their new found readership, with the result that the gap between the writers and readers in India continues to widen further.

Crisis of Identity

In the past sixty years the Sindhi community in India has undergone a massive transformation. The Sindhis in India have made good. The present-day Sindhi in India is by definition highly qualified. There is no profession where a Sindhi has not shown his mettle. Financially, Sindhis in India are well-off; many families have some members working overseas, which has influenced the cultural mores in the community. Naturally, the language too has been influenced by these changes.

By and large, in India most Sindhi children may acquire their mother tongue naturally, ‘may’ because many Sindhi families have already become bilingual or multilingual and the child does not hear only Sindhi in the early years. Those Sindhi children who have picked up the language naturally are able to communicate in Sindhi in limited contexts with their parents and others at home. This is not unusual, for every normal human being is able to master her/his mother tongue by the age of four or five.

However, once the Indian Sindhi child goes to school, his situation changes dramatically. When an average non-Sindhi child goes to school, she/he receives education through the medium of the mother tongue. The Sindhi child, on the other hand, invariably learns through a language other than his mother tongue. One may be tempted to assert that there are many Sindhi medium schools where Sindhi children are taught through the Sindhi medium. Of course, the ground reality is very different. Over the years, the number of Sindhi medium schools has dwindled.

A large number of Sindhis in India live in small towns where their number is often limited. It is impossible to think of Sindhi medium schools in such small centers. In the larger urban areas where it is possible to find Sindhi medium schools, the economic and social pressures compel Sindhi parents to send their children to either English medium schools or to vernacular medium schools. These parents realize, and rightly too, that if they send their children to Sindhi medium schools, then their children might not be able to participate with advantage in the competitive adult world. Therefore, in order to equip their children with the best possible education, they send their children non-Sindhi medium schools. Consequently, over the years, most Sindhi medium schools all over the country have closed down for want of learners.

This is not the entire story – Sindhi children themselves (unless they live in an exclusively Sindhi neighborhood, which is unlikely in most places in India) find the linguistic pressures from their peer group, both inside school and outside, so great that they prefer to communicate in the language of the region, be it Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Panjabi or any other. In fact this pressure is so great that it is not unusual to find Sindhi children speaking with their parents and siblings in the regional language or English.

Currently, Sindhi is used largely by those generations of Sindhis who had some formal education in Sindhi in the pre-Partition Sindh. Generations of Sindhis born in India have very little motivation for using Sindhi in any extended social context. Frequently, their competence in Sindhi is passive; they may comprehend Sindhi in limited communicative contexts, but are not able to communicate in the language. It is not surprising, therefore, that many parents and grandparents speak to their children in the regional language or English rather than in the mother tongue.

Evidence of Attribution

After the 1971 census, the initial language data seemed to indicate that the Sindhi population in India had declined between 1961 and 1971. At first glance this seemed unlikely if not alarming. The present author, drew up a research proposal to study the sociolinguistic profile of Indian Sindhi and Sindhis. It was hypothesized that possibly a sizeable number of Sindhis in India were not declaring Sindhi as their mother tongue. If true, the hypothesis would have serious implications for the Sindhi language and culture in India. The research was supported by the Central Institute of Indian Languages, set up by the GOI to advise the government on language policy and programs.

As part of this research project an all-India pilot study was conducted during 1974-77 to measure the perceptions of Sindhis about their language and culture, and to measure how far they identified with the language and culture and whether they maintained their language identity. For the purpose of the study a questionnaire was constructed to elicit responses across three generations: G1, those who were adults (25+) in 1947, and had received education in Sindh; G2, those who were adolescents (12+) in 1947 and had received primary education through the mother tongue before they migrated to India; and, G3, those who were infants (under 2) in 1947 or were born and educated in India. The results of the study (Daswani and Parchani, 1978) were revealing and startling.

What is the role of Sindhi language then? The Sindhi language for the Indian Sindhi is, in fact, a restricted language almost like a code language which is used for the limited purposes of intra-group communication, limited to the immediate family.

It was discovered that while G1 was largely positive about their language and culture, G2 was ambivalent in their attitude towards the language and culture, and G3 had already moved away and assimilated, by and large, to the local culture. What was revealing was the discovery that even G1 was gradually losing control over the language. On vocabulary recall, all groups had virtually lost the basic native vocabulary and were using Hindi cognates. G1 was not able to distinguish Sindhi dialects one from the other (which were recorded and played to the respondents). There was no awareness of ‘standard’ Sindhi. All respondents considered their own variety of Sindhi as ‘standard’. It was discovered that many Sindhis tended to change identity markers, such ‘-ani’ ending surnames to hide their Sindhi identity.

What is the role of Sindhi language then? The Sindhi language for the Indian Sindhi is, in fact, a restricted language almost like a code language which is used for the limited purposes of intra-group communication, limited to the immediate family. It is used, in a limited context as a means of group (not individual) identity. Paradoxically, it is also attested that some Sindhis do not speak their language because they do not want to be identified as Sindhis. There is a recorded instance of a Sindhi filing an affidavit negating his identity as a Sindhi.

The tendencies and shifts discovered in 1974-77 have continued and the language, especially the written version, has been subject to severe attrition. The writers write in a variety which the average Sindhi neither understands nor uses in his daily life. A fully standard and living language of pre-1947 era has, in a matter of sixty years, become ‘de-standardized’ and decayed (Daswani, 1989; 2006).

Is there a future?

What is the future of the Sindhi language in India? From the present indications it would seem that the future of Sindhi in India is very bleak. It is believed that if urgent steps are not taken the language may become seriously atrophied. The question arises: can anything be done to save the language from total attrition? One possible solution would be to create conditions whereby Sindhi children are enthused to continue to use the language of their childhood. One of the drawbacks, of course, is that currently Sindhi children do not or cannot learn Sindhi in schools. The native mastery that many Sindhi children have acquired over the language during infancy should be strengthened. The immediate task, therefore, is to make it easy and attractive for Sindhi children to learn to read and write Sindhi. The learning of Sindhi literacy should be designed to take as little time and effort as possible.

Resurgence of Oral Culture

A happy augury in an otherwise bleak scenario is the resurgence of the oral culture among the Sindhis in India today. Because of the growth and influence of the electronic media, programs in Sindhi – of music, plays, and films have been on the increase. A host of performers have appeared who perform regularly before live audiences as well as on the electronic media. National TV channels now have programs in Sindhi several times a week. Sindhi NRIs living in foreign countries have been the prime movers in this resurgence. Also, many TV programs broadcast from Sindh are easily available in some parts of India. This resurgence of oral culture will perhaps attract the young Indian Sindhi to his language

Choice of Script

For objectively determining the choice of a script for Indian Sindhi two significant factors need to be considered. These factors can be termed as the Pedagogical Factor and Linguistic Factor.

Pedagogical Factor: As argued above, efforts should be made to make the learning of Sindhi reading and writing for the Indian Sindhi children as swift and easy as possible. One way in which this can be achieved is to exploit the literacy (scriptal) skills that the Sindhi children acquire in school as part of the school curriculum, without imposing an additional script, i.e. the Sindhi-Arabic script, on them, a script which has very limited function in the Indian context. In other words, the reading and writing skills of the Sindhi children in a script already learned in school should be exploited for teaching them to read and write Sindhi.

Therefore, in order to exploit the reading and writing skills of Sindhi children who go to non-Sindhi medium schools, it is necessary to write Sindhi in the script that the Sindhi children have to learn in school as part of the school curriculum. If Sindhi is written in a script that the children have already learned then there is greater likelihood of their reading books in Sindhi and also writing Sindhi for various purposes. On the other hand, if the children have to learn a script especially for reading and writing in Sindhi, i.e. Sindhi-Arabic script, they are reluctant to take on this additional burden of learning, given the limited social and economic functions of Sindhi. Needless to say, children are very perceptive and learn to distinguish between useful and not useful.

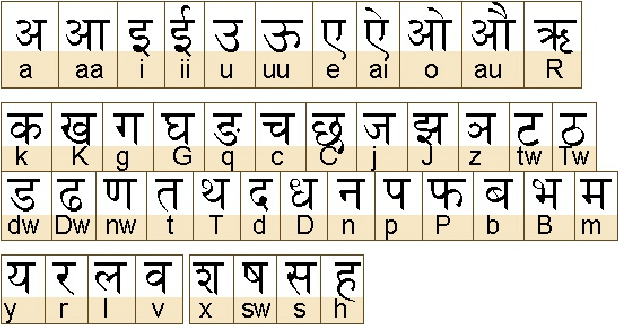

If there is any one script that all Indian Sindhi children have to learn in school, it is the Devanagari script. Over 95% of the total Sindhi population in India lives in what might be called the Devanagari Zone: Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttrankhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Haryana, Delhi and Punjab. All school going children in this zone have to learn the Devanagari script as their first script. Even those children who go to English medium schools have to learn the Devanagari script at the primary school stage. Moreover, even those children who go to Sindhi medium schools and learn the Sindhi-Arabic script, need to learn the Devanagari in the post primary stage. In fact all Indian school children (except in Tamil Nadu) have to learn the national language Hindi in the Devanagari script. It is unreasonable and pedagogically unsound to insist that the Sindhi children write their mother tongue in a script that can only have very limited use and relevance. It would be an enormous waste of resources to teach the Sindhi children a script that has limited use. It would be more profitable to write Sindhi in a script that the children know and read and write in regularly – the Devanagari script.

It is relevant to note here that Sindhi children themselves are in favour of the Devanagari script. In a school in Delhi run by a Sindhi organization, Sindhi children (about 10 percent of the total) are required to learn to read and write in Sindhi. These children are willing to learn the language in the Devanagari script, but not in the Arabic script. Programs of Sindhi language instruction organized by the National Council for the Promotion of Sindhi language are more successful when delivered through the Devanagari script.

Linguistic Factor: Several supporters of the Arabic script have argued that that is the only script suitable for writing Sindhi. A consideration of their claims brings up the second crucial factor, which may be termed as the Linguistic Factor.

Linguistically, an ideal script for any language is one in which all the distinctive sounds of that language are written by distinct symbols. Any script that has more than one symbol for one sound, or one symbol represents more than one sound is inadequate. The Arabic script, which is ideal for the Arabic language, becomes inadequate when employed for any non-Arabic language. The Arabic script has a number of symbols which do not have corresponding sounds in Sindhi. Consequently, several Arabic symbols are used for writing Arabic loan words in Sindhi and the Sindhi words are written with other symbols, although in the speech of the native speakers there is no sound-distinction between the loan words and native words. Sounds like /s/, /z/, /h/ are written with more than one symbol. This leads to learning problems for and spelling errors by Sindhi learners. There are arrested cases where even reputed and recognized writers of Sindhi make spelling errors when they write in the Arabic script.

The Devanagari script, on the other hand, is ideally suited for any Indo-Aryan language, and Sindhi is an Indo-Aryan language. In the Devanagari script all the native sounds of Sindhi, except the implosives, have unique symbols. The implosives can be written with corresponding plosive sounds with a diacritic. Persio-Arabic sounds borrowed by Sindhi already have symbols in the Devanagari since it is used for writing Urdu as well, which has these Persio-Arabic sounds.

Another argument that the supporters of the Arabic script forward is that if we continue to write Indian Sindhi in the Arabic script, then we are likely to maintain links with the Sindhi language in Sindh. This is a weak argument because even a casual examination of the Sindhi language written by writers in Sindh will show that there has been a great deal of Urduization of Sindhi there, while Indian Sindhi has become Hindiized. These changes in the two varieties of Sindhi are natural results of language contact and these tendencies will continue.

The question before the Sindhi community in India is: can we do anything to prevent the Sindhi language in India from becoming extinct through disuse? Clearly, in order that the language survives, it is necessary to ensure that the language is used regularly by the Indian Sindhis, especially the younger generations. The one way of doing this is to make it possible for the Sindhi children to be able to read their language (and want to read it).

The only solution for survival

The only solution lies in writing Sindhi in the Devanagari script. It is indeed ironic that the demand made by the leaders of community in 1948 was thwarted and the language has suffered in the past sixty years. Even if the Devanagari script is adopted as the official script for Sindhi in India, it would take several years, perhaps decades for the language to revive and take an equal place with other Indian languages, growing and flourishing as a major Indian language. The nine Indic scripts (including the scripts used for writing the Dravidian languages) used in India, all come from one source – the Brahmi script (Daswani, 1994). The Devanagari script will give Indian Sindhi a renewed life and return it to the fold of Indo-Aryan languages, which it had been severed from under the influence of Arabic.

_____________________

Courtesy: Sindh Welfare Society India (Posted on May 10, 2015) (Sindh Courier has reproduced the seven year old archival material as an endeavor to gather articles concerning to Sindh and Sindhis wherever and whenever published around the world)