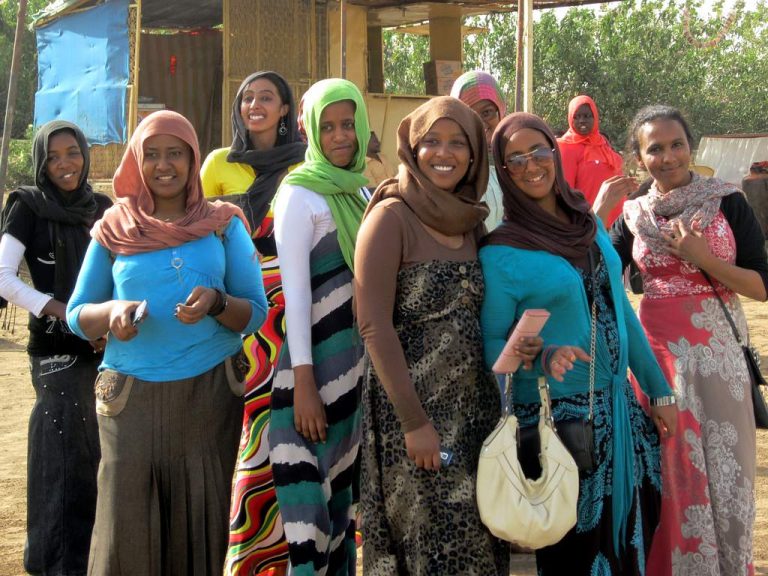

The notorious public order laws enforced previously prevented women from wearing trousers, having their heads uncovered or mixing with men who were not their immediate family members.

Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker

The Sudan government has announced creating a new Community Police Unit, however the general public and the rights activists fear the new police squad will herald the return of the infamous ‘The Public Order Laws’ in the country.

The notorious public order laws enforced previously prevented women from wearing trousers, having their heads uncovered or mixing with men who were not their immediate family members and banned the brewing or drinking of alcohol. The Public Order Laws were repealed by the transitional government, as the laws used to dictate every aspect of people’s everyday lives.

Even though Sudan has been under the rule of a loose and arbitrary version of sharia law for the past 20 years, and floggings are quite regular, the phenomenon still feels very alien to mainstream Sudanese society and inspires revulsion. It has been heartening to see the outcry in Sudan. Both men and women have felt the sting of the whip in the past two decades, and there is a groundswell of anger and lamentation over the dramatic changes in Sudan in the past 20 years.

Sudan has been under the rule of a loose and arbitrary version of sharia law for the past 20 years, and floggings are quite regular.

The public order or morality laws were built on an entire infrastructure from specialized courts to a designated police force spread out across the country. The laws were two-fold; the public order articles were part of the 1991 criminal act and there was also a separate 1996 Khartoum state public order law that was composed of 25 articles (other states also have state-level morality laws such as the “tazkyat al-muitmaa” law in Gedarif state). In the early 2010s, then ruler, Bashir ordered the police to abandon the Khartoum state law after mounting international pressure. However, the police continued to take advantage of the criminal law to continue persecuting nearly 43,000 women a year as per the last known statistic. When the Islamists came to power through a military coup in 1989, they began implementing what they called the civilizational project. The public order was one the manifestations of this project which they described as a tool to “reformulate the Sudanese society on the basis of Islam”

The Islamists used the public order as an important tool to sustain their power through building an environment of fear. This was harnessed by their empowerment of people to call and report any “suspicious” activities. The public order was transformed into a mentality that is widespread across the society. A citizen had the power to call on the public order if he saw girls dressed in “indecent clothing” or if he suspected that a mixed party was taking place in a private house. The law depended on loose articles with phrases such as “indecent clothing” to give its officers the chance to decide and rule out what is decent and indecent. Your safety and freedom was dependent on the opinion and personal preferences of public order officers and random men loitering on the street armed with a misogynistic vendetta.

The Islamists used the public order as an important tool to sustain their power through building an environment of fear.

Article 152 of Sudan’s 1991 Criminal Act, which allows for the flogging of women, hands a disproportionate amount of power to the enforcer, rendering him judge, jury and executioner all at once. Anyone from policemen to plainclothes security officers can take matters into their own hands by invoking the vague and generous allowance in the law, which states: Whoever commits, in a public place, an act, or conducts himself in an indecent manner, or a manner contrary to public morality, or wears an indecent, or immoral dress, which causes annoyance to public feelings, shall be punished, with whipping, not exceeding 40 lashes, or with fine, or with both. The act shall be deemed contrary to public morality, if it is so considered in the religion of the doer, or the custom of the country where the act occurs.

The power given to the public order police to evaluate what is immoral and indecent has resulted in widespread breaches and abuses over the years. There have been many cases where officers have taken advantage of their position to blackmail women or men and to abuse them verbally and even physically. Women are left at the mercy of these decisions without guidelines on what can trigger their arrest in a public or private space, the public order laws (including article 152) are naturally discriminatory against women, since a woman’s dress or conduct is the most likely to offend male security forces. However, in a bad week for Sudan’s image, where the international media’s eyes are focused due to the coming referendum, seven male models were fined for wearing makeup at a fashion show, what is indecent is the application of Sudan’s public order laws, which have done nothing to preserve and enshrine any morality. They have assailed and violated the sensibilities and bodies of victims who are collateral in the government’s failed experiment to exert control via a bogus claim of religious or social decency, the growing discourse by privileged Sudanese individuals calling for the return of the public order to “control” society misses out on two important points: Which society do they want to control? The first point is that the public order police never stopped working in the first place. They continue to terrorize people and especially women. Many activists have reported on how the public order crack down on women in the informal sector and migrant workers in the center and outskirts of Khartoum. They have also continued to crack down on informal alcohol sellers because the 2020 legal amendments have a clear loophole as they allow non-Muslims to consume alcohol, but ban Muslims from consuming and selling alcohol. Feminist activists in Sudan have highlighted how the law puts the seller at fault if she doesn’t ask her clients their religion before offering them her services, which is nothing short of ridiculous. The repeal of a handful of public order articles by the transitional government failed to understand the infrastructure that sets up the system as well as its impact on the society. For starters, this establishment is a multi-million dollar one. It used to bring funds to the state, and was a very good source of income for police officers. In fact, lenient judges who refused to impose hefty fines were often intimidated by police officers and were transferred to other police stations because funds were drying up.

The public order has become a mentality. And a mentality is even harder to mitigate than the law. To bring about true change will take time and sustained efforts in improving school curriculums and countering fundamentalist propaganda. Moreover, more legal reforms are needed to improve the 2020 reforms and also fully tackle the remaining public order and the discriminatory articles that continue to govern the lives of the Sudanese. Meanwhile, the people in wealthier neighborhoods need to understand that the city is crumbling under pressures due to mass urbanization, lack of urban planning and lack of investment in infrastructure. Drugs are an increasing problem. Anyone living in Khartoum knows that. But we cannot limit the discourse on drug distribution to xenophobic rants about migrants and women in the informal sector. We need to talk openly about how the drug business is largely controlled by businessmen and military officers, and how it overwhelmingly impacts certain demographics more than others.

____________________

A poet and writer from Omdurman Umbda –Sudan, Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker works as an English Instructor, Trainer and Freelance Interpreter. He also has been working as a debate leader discussing various topics in many English Institutes, Centers, Academy and schools.

A poet and writer from Omdurman Umbda –Sudan, Yousif Ibrahim Abubaker works as an English Instructor, Trainer and Freelance Interpreter. He also has been working as a debate leader discussing various topics in many English Institutes, Centers, Academy and schools.