The Sudanese are proud of their revolutionary history, and rightly so – but previous revolutions did not bring about the change the country desperately needed.

James Copnall

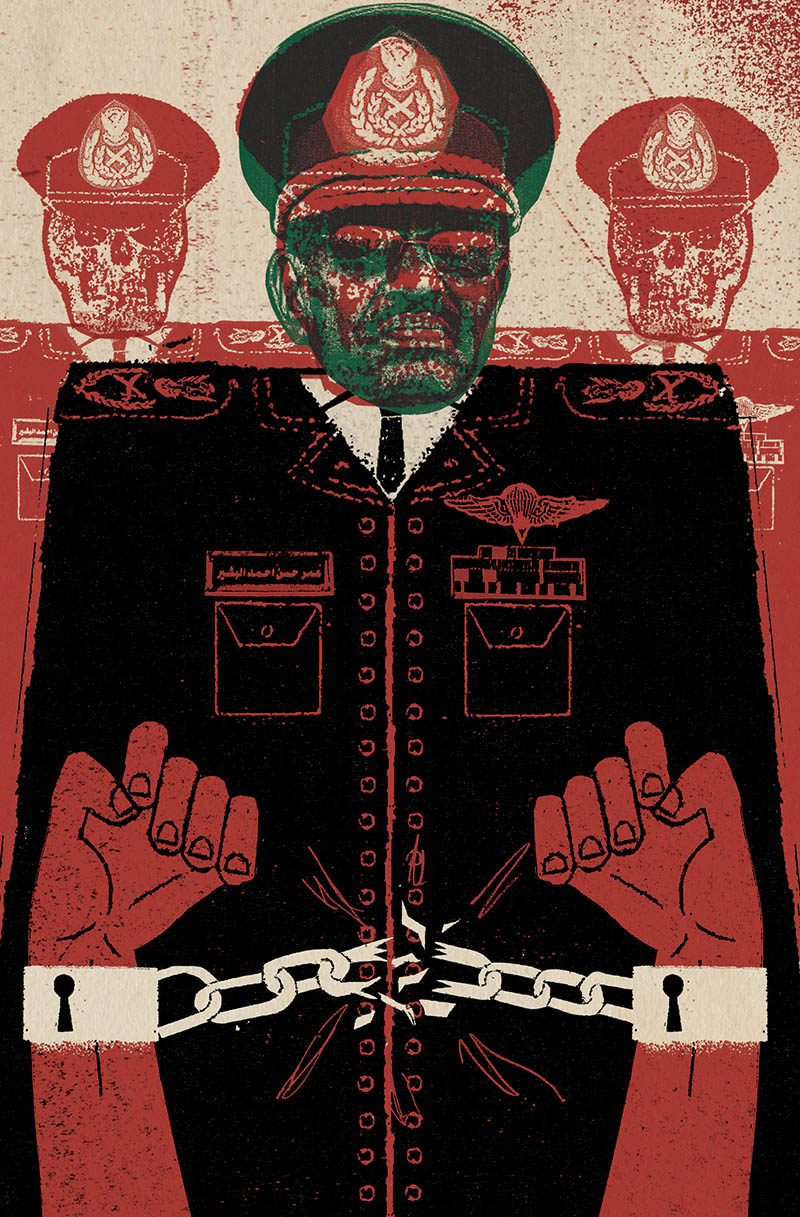

On 11 April 2019, Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown by a popular revolution ending almost three decades in power. After tens of thousands of protesters encircled the military headquarters in the capital Khartoum, ten generals stepped in to remove their former boss, establishing a Transitional Military Council, ostensibly to pave the way for civilian rule. The young protesters had braved tear gas, truncheons and bullets throughout the country; they were following in the footsteps of their parents and grandparents, who had toppled unpopular military leaders in 1964 and 1985. In deposing Bashir, the protesters had achieved what rebel groups, foreign pressure and even indictments for genocide from the International Criminal Court had not managed.

The Sudanese are proud of their revolutionary history, and rightly so – but previous revolutions did not bring about the change the country desperately needed.

One nation?

Sudan was always an awkward colonial creation: diverse peoples with histories of mutual antagonism and exploitation (including slavery) were crammed together at the whim of Turkish and then British and Egyptian colonial masters in 1899. The south saw itself as African, while the political elite in the north defined itself (and the nation) by its Arab origins. In the colonial period, Christian missionaries were allowed to work in southern Sudan, creating further differences with the north, which is overwhelmingly Muslim.

The north – or, to be more precise, the riverine elite from north of Khartoum – has dominated politically throughout Sudan’s history. Successive governments have positioned the state as Arab and Muslim, despite the huge variety of cultures within what was – until South Sudan’s independence in 2011 – Africa’s biggest country.

The first shots of the First Sudanese Civil War were fired in 1955, just before Sudan’s independence in 1956. That conflict ended in compromise in 1972. The Second Civil War, which broke out in 1985, was even longer and bloodier. Bashir’s time in office, after he removed a democratic government in a coup in 1989, had been characterized by conflict and massive human rights abuses. After taking power, he stepped up the war in southern Sudan, in which it is estimated that over two million people died. A peace deal in 2005 stopped the bleeding, but to nobody’s surprise southerners voted almost unanimously to secede in 2011. South Sudan’s independence did not solve Sudan’s problems. Conflicts broke out in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile, areas which had fought alongside the south in the Second Civil War, but were north of the border at separation. Bashir used divisive rhetoric, stating ‘there will be no question of cultural and ethnic diversity’ in Sudan.

The conflict in Darfur – which began in 2003 as an uprising against the government’s treatment of the region’s non-Arab population – rapidly became the worst humanitarian situation in the world. The US described it as a genocide, but took no meaningful action to stop it. Bashir used what Alex de Waal described as ‘counter-insurgency on the cheap’, a combination of air power, armed forces and locally recruited ethnic militias, the feared Janjaweed. They were recruited from ‘Arab’ groups, seen as loyal to Khartoum, as opposed to ‘African’ ethnic groups like the Fur, Zaghawa and the Masalit, who made up the bulk of the rebel forces. Revolts were dealt with using extreme force. Bashir took power promising to Islamise Sudan, using Islamist language and stating that he would govern the country through Islamic principles. From 1999 onwards, this was purely rhetoric – the only real objective was keeping power.

Sudan’s third revolution began in the northern town of Atbara in December 2018. Local officials had removed a wheat subsidy and the price of bread – a Sudanese staple – tripled overnight. Angry crowds burned the local offices of Bashir’s National Congress Party. The economy had been in decline for years, with inflation reaching over 70 per cent. One cause was the secession of South Sudan. When the southerners left, they took three quarters of oil production with them. Oil is Sudan’s main export earner.

Bashir and officials complained that the economic issues were the result of bad luck, poor world oil prices and American sanctions – though the economy did not revive after the latter were removed in 2017. Sudan’s problems were political in making. It is estimated that Bashir’s government spent 60-70 per cent of its budget on the security sector in an attempt to buy the loyalty of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and other armed groups. In addition, Sudan’s toxic politics – including Bashir’s indictments from the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity – made it impossible to get relief on Sudan’s debt (well over $50 billion), or obtain new loans from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

After the demonstrators took to the streets in Atbara, protests spread to other towns across the country. On 25 December 2018, a new body, the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), made up of doctors, lawyers and journalists, attempted to deliver a petition to the presidential palace in Khartoum calling on Bashir and his government to step down. On 1 January, the SPA, along with several other political and social groups, signed the Declaration of Freedom and Change, calling for Bashir to be replaced by a transitional government to end civil wars, rethink the constitution and put the state back on its feet. Protests about the crumbling economy had become political. The slogan on the streets was ‘Tasgut, Bess’ (‘Fall, that’s all’).

The uprising has often been portrayed as a sort of delayed Arab Spring. This infuriates the protesters. The Sudanese have overthrown unwanted military rulers twice before. In the 1964 October Revolution, Ibrahim Abboud agreed to step down. Protests had intensified following the death of a student demonstrator, Ahmed al Quraishi. The Sudanese historian Yusuf Fadl Hasan praised ‘the determination and moral force with which unarmed citizens, led by the intelligentsia, brought military force to an end’. Just over 20 years later, mass protests broke out against another military leader, Jaafar Nimeiry. He had come to power in a coup in 1969. Just as in the current uprising, the trigger was the economy. On 6 April 1985, the military stepped in, before handing power to civilians. This history has informed every attempt by the Sudanese to protest since 1989.

The end of Bashir

Bashir’s response was a mixture of intimidation, cajoling and propaganda. Dozens of protesters were shot dead. Hundreds were arrested. Officials accepted the demonstrators’ economic frustrations, but sought to blame the peaceful uprising on Darfuri rebels, using the well-worn politics of division. It didn’t work. ‘We are all Darfuris’, the protesters chanted. By February, as the protests showed no sign of abating, Bashir became desperate. He sacked his government, declaring a nationwide state of emergency. It was not enough. The protesters wanted nothing less than an end to the Bashir years. On 6 April – the 34th anniversary of the overthrow of Nimeiry – a massive demonstration met outside military headquarters in central Khartoum. ‘We thought we were going to be killed’, said one protester. ‘But instead we were able to get all the way to the army headquarters.’ Over the following days, security agents made intermittent attempts to dislodge them, using live ammunition. But members of SAF fired back. Ordinary soldiers were unable to countenance the massacre of civilian protesters, following the example of previous generations of soldiers in Sudanese revolutions. When President Bashir reportedly told his closest confidants that he was prepared to stomach a massacre if it kept him in power, the senior generals decided to act. In the early hours of 11 April they blocked Bashir’s means of communication, changed the troops at the presidential residence and informed him that he had been overthrown.

The subsequent military council’s willingness to hand over power to civilians is the great remaining question. A deal has seemed close at points. The civilian protesters insist on a civilian-led government. The military has accepted the need for a civilian parliament, led by a civilian prime minister. The great sticking point is the composition of a ‘sovereign council’, a supreme body above the Cabinet. Both the military and the civilians want to be in the majority. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are encouraging the military to hold firm, as is Egypt. Western countries, led by the US, the UK and Norway, have called for a swift handover to a civilian administration.

Third time lucky?

The protesters knew that, as soon as they left their sit-in outside the military headquarters, ‘our revolution would be over’, as one puts it. So they stayed, creating a mini-city in a matter of weeks: a stage for announcements and concerts; any number of speaker’s corners to discuss politics and Sudan’s age-old problems of racism and tribalism; barricades where anyone coming to the protest was searched; a system for removing waste; doctors on call; even a school for street children. Revolutionaries discussed the sort of society they want Sudan to become. In the early hours of 3 June, Transitional Military Council forces swept in to chase away the protesters and closed their sit-in. The protesters promised to step up civil disobedience to achieve their goal of a civilian government. The final chapter of Sudan’s third revolution is still unwritten, but it is impossible to dispute what it has already achieved.

___________________

James Copnall is the author of A Poisonous Thorn in Our Hearts: Sudan and South Sudan’s Bitter and Incomplete Divorce (Hurst, 2014).

Courtesy: History Today