The purpose we articulate must be higher than skills or job training or self-actualization. Education is about teaching young people to know and love the highest things — truth, goodness, and beauty.

By Nazarul Islam

For more than a half-century, mainstream American education has lacked a clear, transcendent purpose.

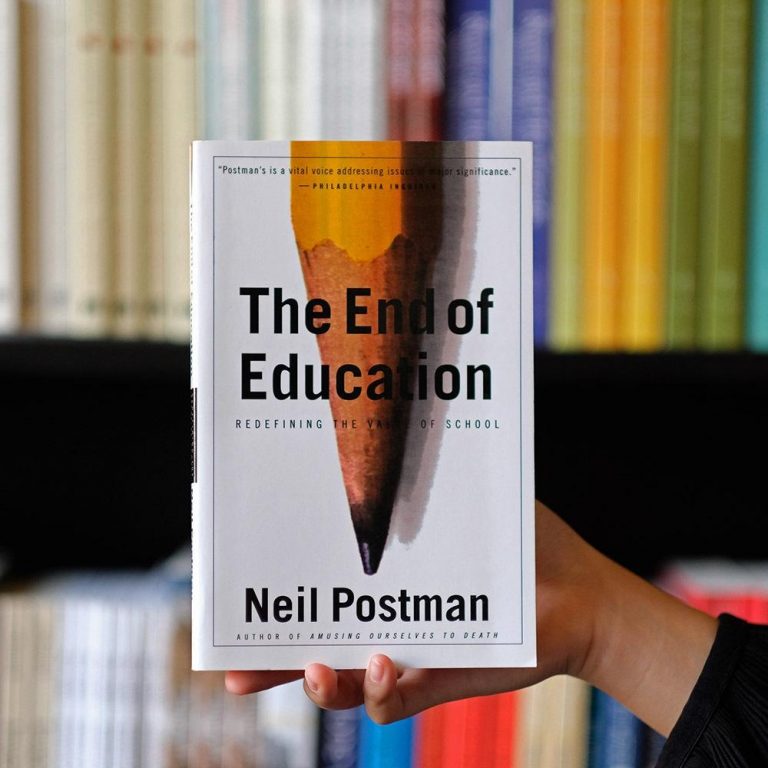

We have abandoned the telos (end term) of education and reduced education to a technical method. In his book “The End of Education,” twentieth-century media ecologist Neil Postman argues that there is no surer way to bring education to an ignominious end than for it to have no end. In other words, if we don’t understand the purpose of education, we won’t be able to appropriately and responsibly use the techniques and the technology we have at our disposal to facilitate a worthwhile education.

Postman’s critique of education is framed within his ideas about technology. Both as a professor at New York University and throughout his writings, he argues that even the smallest change in human culture affects the whole system — especially when related to technology.

The technology gradually introduced into culture and education has changed how people communicate and relate in profound ways. Unfortunately, Postman argues, the changes have largely been negative, mostly taking away from the fullness of human experience.

Writing in the late 20th century, Postman pinpoints the computer as an example of how technology has changed education. As information passes through a computer, the computer itself doesn’t change — the hardware and operating system stay the same, and it remains only the receptor or transmitter of data.

Postman suggests we have begun to regard students in the same way, as mere receptors and transmitters of information, meant to passively receive data and then transfer or reproduce it. (Standardized tests are a great example of this mentality.)

In the classical tradition, however, education has been understood to change people fundamentally. Plato called education “a conversion of the soul,” a turning toward wisdom and truth. For thousands of years, education has been concerned with forming human beings. As such, the metaphor of a computer is structurally flawed. Education doesn’t work this way, nor should it.

Postman reminds us, furthermore, that the medium truly is the message. We convey things to students not only in what we teach but how we teach. If all one does is simply stand in front of students, talking at them while they write down notes, they are tacitly taught that learning fundamentally involves a passive receptivity to information.

On the other hand, if students are engaged in a discussion through Socratic dialogue — asking deep, important questions and then working collaboratively to find answers — they are taught that the nature of learning is dynamic and requires attention, conversation, and friendship.

Despite his critiques, Postman doesn’t propose we do away with technology altogether.

Technology isn’t bad in itself. The problem is that we have too readily and uncritically accepted it. We have created something that we don’t fully understand and can’t sufficiently control — its effects and changes to our world are at once deep, problematic, and unexplored. In response, Postman urges us to consider where technology properly belongs and to ponder how it can be appropriately channeled to serve a higher purpose.

According to Postman, we must recognize our current situation and then work to articulate the purpose of education so that it has a narrative and a goal. In our post-progressive world, we focus almost exclusively on the technical questions: how to improve graduation rates, raise test scores, or transmit information more efficiently. Meanwhile, the transcendent metaphysical questions — why are we doing this? What is the purpose? — Too often are abandoned.

Today, our lives are saturated with information, a stark reality Postman also counts as one of the most negative effects of technology on education. Advances in computers have led to an information glut. We are so awash in information that we don’t know what to do with it or how to organize it. More critically, we don’t know how to discern what is useful or important from what is not.

If education is about the formation of a certain kind of human being, about providing a guide for how to live virtuously and wisely, or even about how to solve complicated societal or political problems, the answer is not always more information. Is it a lack of information about how to grow food that keeps millions of humans across the globe hungry? Is it a lack of information that brings physical decay to our cities?

Is it a lack of information that leads to an ever-growing presence of mental illness? The fact is, there are few political, social, and especially personal problems that arise because of insufficient information.

By abandoning a transcendent purpose for education, a narrative that explains its final goal, we threaten to end education altogether.

The purpose we articulate must be higher than skills or job training or self-actualization. Education is about teaching young people to know and love the highest things — truth, goodness, and beauty. It is about cultivating them into virtuous and wise human beings. Although Postman died in 2003, his ideas and warnings remain relevant and prophetic.

We would be wise to heed them now — before it is too late.

[author title=”Nazarul Islam ” image=”https://sindhcourier.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Nazarul-Islam-2.png”]The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his 119 articles.[/author]