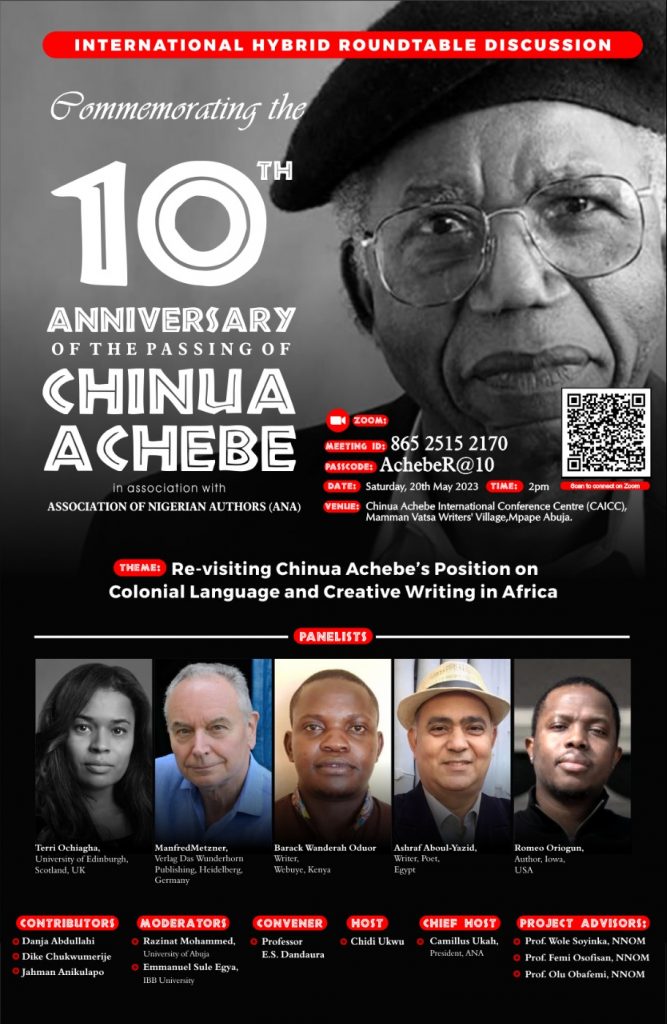

The International Hybrid Roundtable Discussion was held during 3-day conference (May 19-21) on 10th anniversary of the passing away of Chinua Achebe in collaboration with Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) in Abuja

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid | Egypt

As we read about African literature, in Egypt and the Arab world, we will find all roads lead to the late critic and novelist Dr. Radwa Ashour. In the same time, modern researchers will not deal with non-Arabic African literature without referring to Radwa’s foundational book (The Follower Rises), which dealt with the novel in West Africa.

She wrote in her introduction: “This is a research on a subject that is not explored in Arab criticism except in the narrowest limits.”

“The issues raised by a study of this kind are not far from the daily concerns of the Arab reader and the problems faced by African writers, whether they are political problems arising from the colonial reality and the result of the national liberation stage, or creative problems related to the writer’s position on his cultural heritage and the European literary heritage that produced the novel form”, Radwa wrote 50 years ago.

The motive behind choosing West Africa was the participation of its societies in its economic, social, political and cultural reality to a large extent, which makes it easier to deal with the fictional production of her book in one study without falling into generalization or oversimplification.

West Africa has witnessed a creative momentum since the end of World War II, making it one of the most generous regions of the continent, and making its writers constitute the majority of African writers who write in English and French, as well as a deep conviction of the researcher of the need for cultural communication between third world countries in general, and the African continent in particular.

Dr. Radwa Ashour categorized Western critical writings on African literature within two clear directions; – The mouthpieces of the imperial cultural establishment who practice a kind of cultural terrorism that manifests itself in raising the status of one writer and degrading another unjustly, but rather for political purposes in their souls, such as the novel by the Malian writer Yambo Ouologuem (August 22, 1940 – October 14, 2017) “The Duty of Violence” (1968), which the critics applauded and described by some of them as the first truly African novel, although it claims that this continent has always been a scene of violence, and that the colonial experience did not bring anything new and was not worse than before.

The motive behind choosing West Africa was the participation of its societies in its economic, social, political and cultural reality to a large extent

As for the second trend, it is represented in the critical writings that its authors strive to present, understand and evaluate African literature, and we note, despite this, that most of these writings fail to make right critical judgments because of the conservative political stance of the critic who refuses to deal with political literature except on the basis that it is propaganda literature.

Dr. Radwa Ashour did not find those novels translated into Arabic, so she was forced to briefly narrate them for Arab readers, except for one novel, (Things Fall Apart) by the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe (November 16, 1930- March 21, 2013), which was published in 1962 in UK and was the first novel to be published in Arabic, in Cairo, in the “African Writers” series.

This early version of the novel was translated into Arabic by Dr. Injil Boutros Semaan for the Egyptian General Book Organization in 1971. Another Arabic version was translated by Samir Ezzat Nassar for Al-Dar Al-Ahlia, and a third Arabic version was translated by Ahmed Khalifa for the Arab Research Foundation in 1990. Finally, the General Authority for Cultural Palaces re-translated the novel in a new version, for the Global Horizons series in Egypt in 2014 with the translation of Abdel-Salam Ibrahim, within the project “The Hundred Books.

It is rare for a non-European or non- American novel to have such multiple translations, even the novel’s title inspired a writer (Hanin Al-Basha) in a work published by the Center for Arab Literature in 2017, and why not, and it is the same title that Achebe drew from a verse in the poem of the poet William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming:

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

We also do not forget the effort of Dr. Ali Shalash in his book on “African literature”, which considered Achebe, in West Africa, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in the east of the continent, to represent their regions well, in addition to being the most influential. Dr. Ali Shalash wrote: “The hero of Things Fall Apart has been likened to the characters of Greek tragedy that appear again, but in a different way in Achebe’s second novel, which is related to its colleague in many ways, and if the first is chronologically from beginning to end, then this begins at the end, and gradually returns to the past until you reach the beginning!”

We also do not forget the effort of Dr. Ali Shalash in his book on “African literature”, which considered Achebe, in West Africa, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in the east of the continent, to represent their regions well, in addition to being the most influential. Dr. Ali Shalash wrote: “The hero of Things Fall Apart has been likened to the characters of Greek tragedy that appear again, but in a different way in Achebe’s second novel, which is related to its colleague in many ways, and if the first is chronologically from beginning to end, then this begins at the end, and gradually returns to the past until you reach the beginning!”

Radwa’s book (The Follower Rises), was divided into eight chapters: first chapters dealt with the emergence of the novel art in West Africa as a form of rebellion against the ideological content of colonialism, the role chosen by the writer in confirming his national culture, and the pioneering efforts in the groups of the novel form by referring to African folklore and drawing inspiration from its stories and legends, through a study of some of the novels of the Nigerian writer Amos Teutola. These writers had a common tendency to glorify the African personality and its civilized past as a reaction to the position of the colonizer. This was against the trend opposing this romantic position, presenting models for the critical vision of the African reality.

In the fifth chapter, Dr. Radwa Ashour raises the issue of the relationship between the African writer and his history, which was obliterated and distorted by the colonialists, by addressing two novels by the Nigerian writer “Chinua Achebe”, one of which is “Things Fall Apart”.

This commitment to the political problems of the African reality prompted Western critics to criticize the African writer for what they called excessive enthusiasm

The African writer is preoccupied with the political and social entanglements of his daily reality, and this preoccupation occupies the first place in his creative writing, which makes the vast majority of contemporary novel production in Africa take on a political character and conveys a social vision.

This commitment to the political problems of the African reality prompted Western critics to criticize the African writer for what they called excessive enthusiasm. Responding to these critics, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe writes:

“I think… and I have believed from the first moment that I began writing that earnestness and enthusiasm are perfectly appropriate in my case. Why? I think because I have a deep need to change the conditions under which I live, to find a place for myself a little larger than decided for me in this world. The missionary who left the luxuries of life in Europe to wander in my primeval forest was so earnest and zealous. He had to be, for he came to change my world. And the empire-builders who turned me into a human being under British protection knew the importance of earnestness and zeal…Now it seems clear to me if I were to change the role and the identity which these agents of colonialism had so earnestly decided for me, I would need to recover some of their enthusiasm. I cannot of course dream of achieving this by meditating.”

Thus, in contrast to the image of the calm European artist, the image of the African artist stands out who accepts willingly to pay from his life and art the debts of the ancestors and plays the role of the teacher, stressing that African art has always enjoyed a prominent social function, and that this heritage must be continued.

In this regard, Chinua Achebe says, as quoted in the book:

“I would be satisfied if my novels (especially those set in the past) did nothing more than teach my readers that their past, with all its shortcomings, was not one long night of savagery from which the early Europeans awoke them and saved them in the name of God. Perhaps what I write is an applied art that is different from pure art. But it doesn’t matter. Art is important, but education is also important, the kind of education that I have in mind. I don’t see a contradiction between the two.”

The words of “Achebe,” as Radwa wrote, express the position of many African writers, and even third-world writers. They are not only due to a sense of responsibility, but also stem from a deep conviction that art has no preference over life or over the national affiliation of the writer.

Yes, the African writer chooses his homeland first, and it is a choice that leaves him at one time behind prison bars, and at another as a homeless person in exile. When the writer ceases to act the role of conscience in his community, he must admit that he has chosen either to completely disavow himself or to withdraw to a registered site of a bereaved juvenile or a forensic doctor dealing with a dead body.

If a great artist anywhere is the conscience, ear and eye of his society, this role for the African artist is an ancient role played by epic narrators, mask makers and other artists in African traditional societies

It is true that the writer’s glorification of his past in the face of colonial exile was a positive step in a specific historical circumstance. We cannot deny the pioneering efforts of the Négritude writers and the influence of their writings on the writers of the black world beginning in the late thirties and over the next two periods. But the absolute exaltation of everything that is African threatens to fall into romanticism, and this is the simplest of the stumbling blocks, but the most dangerous thing is that it also threatens to overlook the disadvantages of the African leaders who took power after independence, and the dire effects of this overlooking and the massacres that took place in the shadow of national independence and the oppression to which they are exposed.

If a great artist anywhere is the conscience, ear and eye of his society, this role for the African artist is an ancient role played by epic narrators, mask makers and other artists in African traditional societies. The artist in those times was a servant of the group and a master among them, accompanying its life in order to continuously fulfill its needs.

The writers in West Africa cling to the image of the artists in their heritage and are inspired by it. Wole Soyinka writes: “When the gods die – that is, they are destroyed – the sculptor is summoned, and a new god, who excludes the old, comes to life. He is thrown into the forest, where it decomposes and is eaten by termites. It gives the new the same characteristics of the old, and it may acquire other new characteristics. In the field of literature, the writer plays a similar role in nullifying the effect of the old, as he plays the role of termites, either by ignoring the old god or by creating new ones.

The Follower Rises has been the torch to light the way for many papers and reviews of African literature, especially the works of Chinua Achebe. Some academic thesis have considered it as a reference, for an I example “THE NOVELS OF CHINUA ACHEBE: “A Portrait of Pre and Post-Colonial Society, an M.A. thesis submitted by Egyptian researcher Mona Prince, who considered “Okonkwo is a man drawn by a dream and driven by fear, the dream of becoming a great man in the clan, and the fear of becoming or thought to be weak and a failure like his father. Throughout the novel, fear is the strong passion that moves him to action. One of the important functions of the opening chapter in this novel is the juxtaposition of the characters of both the father Unoka and the son Okonkwo, and how the father’s character had the most unfortunate influence upon the son.”

With the advent of the white man, things began to change faster, the people and the customs, except Okonkwo. Okonkwo’s fear and dream never changed. And he will fight anything and any force that stops him from achieving this end. Knowing that he lost his former position among his people during his seven years of exile, Okonkwo resolved to regain what he has lost and to rebuild his dream.

Finally, the issue of the fictional form of African creativity remains, and I see that (Things Fall Apart) represents a play on non-European forms of narrative narration, and perhaps it is closer to the framework of the stories in the Arabian Nights; where each chapter gives a separate and connected tale, that can continue for a thousand and one things, falling apart and rising again, to draw a self-contained African epic.

________________

Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is a renowned poet, novelist, journalist, travelogue writer of Egypt. He is author of over three dozen books and Editor-in-Chief, Silk Road Literature Series.