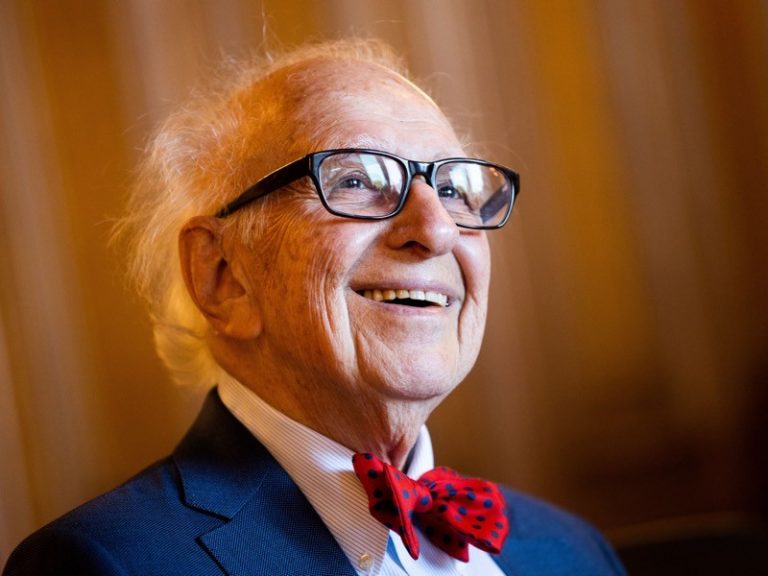

The Nobel-winning neuroscientist has been studying connections on an ever-grander scale.

By Alison Abbott

In 1996, Denise Kandel warned her husband that were he to win the Nobel prize for his pioneering work on memory, then it should be later rather than sooner. Laureates too often turn into socialites, she warned, and stop contributing to the intellectual life of science.

Just four years later, Eric Kandel shared the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He was then 71, an age when he could legitimately have rested on his laurels. But resting is not among Kandel’s many strengths. His new book, There Is Life After the Nobel Prize, outlines his achievements of the past couple of decades — numerous enough to dispel Denise’s fears, he writes. It is hard to disagree.

The volume adds to Kandel’s respected literary oeuvre, which ranges from neuroscience textbooks to highly original popular science. But it is slight, and feels like a coda. In it, he summarizes his post-Nobel research (on learning and memory deficits in addiction, schizophrenia and ageing), writing and public outreach. And he acknowledges colleagues and sponsors of his long career, particularly the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Chevy Chase, Maryland, and Columbia University in New York City, where he remains a professor and institute director. A fuller and more poignant autobiography can be found in Kandel’s 2006 book In Search of Memory. There, he explains why his traumatic childhood in Austria drew him to study the mechanisms of memory. That book also presents a marvelous history of neuroscience.

Making sense

Kandel was born in 1929 in Vienna. His family was Jewish and owned a toy shop. When Hitler annexed Austria in 1938, his parents began their year-long effort to emigrate. They finally arrived in New York shortly before the outbreak of World War II, physically unharmed but psychologically traumatized.

Incidents from that final year in Vienna etched themselves into Kandel’s brain: the burning of synagogues on Kristallnacht in November 1938, eviction from the family apartment just days after his ninth birthday, being shunned by his school friends and roughed up by neighborhood bullies. Such memories would flash unannounced into his consciousness years later.

His desire to make sense of his experience led him to study history at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to which he won a scholarship. There, a girlfriend introduced him to psychoanalysis. Thinking that this new way of analyzing the patterns of mind and memory could bring him the understanding he sought, he entered medical school at New York University.

Disillusionment with the non-empirical nature of psychoanalysis soon set in. Kandel realized that progress required a return to basics. In the 1950s, he joined the avant-garde neuroscientists studying the physiology of the brain, such as the electrical properties of neurons. Kandel went a radical step further. Unpicking exactly how neurons facilitated learning and memory required study in a very simple organism, and a very simple learning-dependent behavior, he decided.

The reductionist approach he chose — the protective reflex of gill withdrawal in the sea slug Aplysia — raised eyebrows. Most neuroscientists thought that simple invertebrates could never elucidate the complexities of mammalian memory systems. In fact, Kandel discovered that as the slug learnt which environmental conditions required it to suck in its gills for protection, its synapses — structures that allow electrical or chemical signals to transmit between neurons — were altered.

He went on to describe the neural circuitry and molecular biology involved in short- and long-term memory in the slugs. Determining these principles won him the Nobel Prize, and they have proved true for all creatures, humans included. Post-Nobel, he has studied memory in higher organisms including mice, turning out high-profile papers well into his eighties.

The Nobel experience widened Kandel’s horizons beyond experimental science. The success of In Search of Memory awakened in him the desire for broader communication. I met him in Vienna in 2008, when a German-language documentary based on this book was about to have its premiere (Nature 453, 985; 2008). Radiating energy, he had started to make peace with the city of his birth.

His new book relates how, following the prize, Austria’s president, Thomas Klestil, made overtures. Kandel initially rebuffed them, saying that he considered himself a Jewish American scientist. But then he proposed that Klestil honor him by setting up a symposium at the University of Vienna on Austria’s response to the Nazi doctrine of National Socialism, and its implications for science and the humanities. Since that symposium, in 2003, Kandel has acted as an adviser to a couple of Austrian neuroscience organizations. “My relationship with Austria is becoming more comfortable, although it’s got a way to go,” he writes.

Since the 1960s, he has collected twentieth-century German and Austrian expressionist art, an interest that led to his 2012 book The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. This superb volume illuminates the period when modernists of all shades were engaging with the internal workings of the mind. Sigmund Freud was developing psychoanalysis; novelist Arthur Schnitzler was pioneering the interior-monologue mode of narration; expressionist artists including Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele were portraying subjective emotions. Kandel guides readers through this cultural history and describes how the neuroscience of perception explains so much of our intuitive understanding of art. It epitomizes Kandel’s breadth of vision. There has indeed been life after the Nobel prize.

_____________________

Courtesy: Nature