Kutchi, Migration, and East African Asian Identity in the Indian Diaspora

Kutchi, Migration, and East African Asian Identity in the Indian Diaspora

The author explores the historical origins of her family language, Kutchi, and its enduring legacy through years of migration and settlement across continents.

By Omme-Salma Rahemtullah

Whenever I fill out a bureaucratic form asking for my mother tongue, I hesitate. What is an innocuous question for most immigrants to North America has always struck me as being deeply political and consequential. The answer is simple enough: I grew up speaking Kutchi at home, so that’s my mother tongue. Except, Kutchi is not a written language, it’s an oral one, and even the term itself has a variety of spellings. Spoken only by a minority of the Indian diaspora in the West, it belongs to a group so small that I wonder if it’s an invention of our community – sometimes I question if it’s even really a language at all. Of course, in theoretical interpretations all languages are inventions (this is what you come to think after reading too much Noam Chomsky and Stuart Hall), but the ways in which Kutchi seems to be malleable and unrecognized is in contrast to the stability and familiarity of languages such as Gujarati which are easily recognized in North America. So, the question always remains: do I even have a mother tongue?

Kutchi and its history has become central to my work as an Archival Creators Fellow at the South Asian American Digital Archive, for which I am documenting the settlement of Ugandan Asian refugees in South Carolina who were expelled from Uganda in 1972 by then-dictator Idi Amin. Asians have a long history of trade and settlement in East Africa and over generations have maintained their cultural Indian backgrounds, including language.4 There is a wider history of voluntary migration of East African Asians to North America – of which I am a part, having left Tanzania at a very early age and growing up in Toronto. Kutchi is an enduring legacy of these migrations and settlements, having followed migrants from India to East Africa to North America.

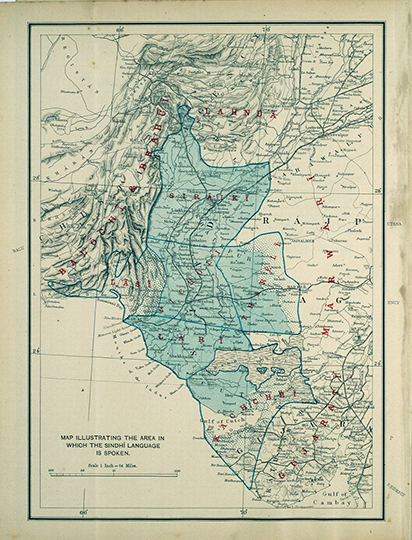

Kutchi originates in the region of Kutch (or what’s known as the Rann, or salt marsh, of Kutch), in the northwest part of the state of Gujarat, in the northwest part of India. To the north, Kutch shares a border with Pakistan; to the west it juts out into the Arabian Sea. The regions of Kutch and Kathiawar, where a sizable number of early Indian migrants to East Africa originated, were excluded from early histories of the state of Gujarat (due to their geographical isolation), only becoming discursively and socially a part of the state of Gujarat in the 1960’s. As a result, the language of Kutchi which developed and traveled to East Africa has distinctive characteristics that are not common in the Kutchi spoken in India today. Though the use of Kutchi among Asians in East Africa is widespread, especially among those who migrated from Kutch and Kathiawar in the late 1800s to early 1900s, there has been no systematic survey of the language and its use in East Africa. With one exception, a study conducted in Tanzania in 1971 as part of the Tanzanian National Survey which found that Asians spoke 5 languages: Kutchi, Gujarati, Punjabi, Konkani and Urdu, using Kutchi in 52% of their daily interactions inside and outside the home (Gujarati in 14.5%, Swahili in 7.3% and English in 26%). This demonstrates the lasting legacy of Kutchi in East Africa and also to the educational systems of Asians in the region. There are no updated numbers regarding the use of Kutchi in East Africa, Europe or North America, but the language has endured – as evidenced by people still speaking it, myself and my interviewees for this project included.

Kutchi as a Map of Migration

As a Kutchi speaker from East Africa living in North America, I never thought too much about how the language and its use would have changed from the ways my great-great grandparents would have used it in India. In fact, for the longest time growing up, I didn’t even realize that some of the words I had always assumed were Kutchi were in fact Swahili. Even though I am a fluent Kutchi speaker, I know some common words only in Swahili: for example, in my mother’s kitchen, a cooking pot, was always called sufrio, which is Swahili. My English-to-Swahili dictionary reveals that the word for pot in ‘proper’ Swahili is sufuria, implying that sufrio is some sort of adapted Swahili used among East African Asians. I asked my family what the Kutchi word for sufrio is and was told that it was tapelo – so clearly the Kutchi o ending for tapelo was adapted to the a ending for sufuria by Asians in East Africa. Admittedly, this is anecdotal ‘evidence,’ but it does point to an important way in which language travels and adapts. Mahida Bachu, in one of the only community portraits of the East African Kutchi language I could find, also notes that Swahili words are modified by Asians to fit Kutchi pronunciation patterns, so that sahani (plate), mboga (vegetable) and ndizi (banana) are modified by Kutchi speakers as saani, boga and dizi. It is not lost on me that a lot of these mixed words are all kitchen related, which reveals a lot about how Swahili was used and passed down by Asians in East Africa: along gendered lines and in the context of “Asians” speaking and interacting with “African” domestic workers, alas an article for another day!

Ashraf, one of my interviewees whose father moved to Uganda from Kutch, told me a story about the loss of Kutchi words:

“Ghar mei kutchi bolnavas, asanji kutchi judi vi, khathavari mix na andhar.” “Hevar kutchi thorik change thavayai, parn munjo daddy etlo kutchi kerdhava. It’s like you know, like if you say excuse me or move a little further, my dad would say ‘paria hhat’; it means move forward. Ya we don’t say that now. So some of the words my dad used to use, he always used to say bhalah, which mean ‘hei boh saro thiyo’. So my brother in Romania munkeh message halaineh, tho iyh chondo ‘bhalah hiy vatu boh sarao thiyi’ au inkeh choise tun bhalah bhala kida kayiye mehdili, tun tho mun khada nindo ayien. Hi baba ke yaadh kharinti bhalah chondovo. Asan kutchi bolotha inmeh Swahili words boh ventha.”

Since Ashraf’s father was the one who moved from India, she was able to trace the changes migration brought to the Kutchi language within one generation, in a way that was very noticeable and adaptive to the East African region.

(Continues)

___________________

About the Author