On February 19, 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court decided unanimously to bar South Asians from becoming American citizens.

The March 10 issue of The Literary Digest celebrated this decision. “Hindus too Brunette to Vote Here,” it declared, with a photograph of a South Asian man accompanied simply with the caption: “The Problem.”

The U.S. Supreme Court had decided unanimously to bar South Asians from becoming American citizens and to denaturalize those who had already done so in the landmark case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.

Thind, who immigrated to the United States in 1913 and even trained to fight with the U.S. Army in World War I, had begun his personal struggle for citizenship five years earlier, in 1918. Through its decision, the Supreme Court quashed the hopes of Thind and fellow South Asians in the United States to gain full recognition as American citizens.

The legal case rested on the question of who was considered “white.” Thind argued that according to the “racial science” of the day, South Asians were descendants of Indian Aryans who belonged to the “Caucasian race,” and thus were “white” and eligible for citizenship.

Thind lost, and in its decision the Supreme Court noted that the words “white persons” were words of “common speech and not of scientific origin.” It further concluded that the Hindu “is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation.”

The 1923 decision had a devastating impact on the nascent South Asian American community. In conjunction with other anti-immigration legislation, South Asians were prevented from establishing themselves in the United States for years to come.

It was not until 1946, more than two decades later, that South Asians were able to become U.S. citizens.

The “Asiatic Barred Zone” of 1917

The 1923 Supreme Court decision barring South Asians from citizenship was the culmination of decades of anti-South Asian sentiment in the U.S., marked by xenophobic rhetoric, racial violence, and restrictive immigration legislation.

Here’s some background: South Asians began immigrating to the United States in larger numbers nearly 130 years ago, beginning in the late 1800s. These early immigrants were primarily Sikh men from the Punjab region of British India, who mostly settled in the western parts of the United States (California, Oregon, and Washington) and western Canada (British Columbia). For the most part they worked as laborers, on farms, fields, lumberyards, and mills.

There were smaller numbers of South Asians who came to the United States as students, pursuing their education at universities across the country — and a handful of others, who came as merchants, religious leaders, travelers, or for other purposes. There was also an early wave of Bengali Muslims, first peddlers who settled in port cities like New Orleans, and later lascars (ship workers), intermarrying into Black and Puerto Rican communities in New York, Baltimore, and elsewhere. This early population consisted almost exclusively of men, because restrictive immigration policy made it nearly impossible for South Asian women to immigrate to the U.S. There were a small number of exceptions however, like Anandibai Joshee, who completed her medical degree in Philadelphia in 1886, and Kala Bagai, who arrived in San Francisco in 1915 with her husband and three sons.

The harsh reality that these early immigrants faced was one of overt racism and xenophobia. A newspaper headline from the San Francisco Call in 1906 gives a sense of the sentiment in the country at that time: “Our First Invasion by Hindus and Mohammedans,” it declared.

And another, from the lumber town of Bellingham, Washington on September 16, 1906: “Have We A Dusky Peril? Hindu Hordes Invading The State,” it proclaimed.

Less than a year later, there was a race riot in that same town, where the group of Punjabi laborers who had settled to work in the lumber industry, were attacked and violently chased out of Bellingham by a mob of approximately 400-500 white men. This act touched off anti-Asian mob violence in other parts of Washington, California, and British Columbia.

The xenophobic popular sentiment in the country was also reflected in Congress. Beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, Congress started passing a series of laws tightening restrictions against Chinese migration.

As a response to the increasing immigration from South Asia in the early 1900s, legislators searched for a way to exclude South Asians as well. In 1914, the U.S. House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization held the “Hindu Immigration Hearings,” to publicly debate South Asian immigration. Eventually, on February 5, 1917, exclusionists succeeded in overturning a presidential veto by Woodrow Wilson to pass a law barring anyone traveling from a defined “Asiatic Barred Zone” from entering the United States.

The barred zone included “India, Siam, Indo-China, parts of Siberia, Afghanistan, and Arabia, the islands of Java, Sumatra, Ceylon, Borneo, New Guinea, Celebes, and various lesser groups with an estimated population of 500,000,000.” Congressman John E. Raker of California a proponent of the Act explained: “we ought to make our laws sufficiently strong as to … exclude all Asiatic laborers now, so that there will be no question in the future.”

The anti-immigrant sentiment of the early-1900s is painfully reminiscent of the recent political and social climate. In fact, it was almost exactly 100 years to the day after the “Asiatic Barred Zone” of 1917 was created that President Trump signed Executive Order 13769 (commonly known as the “Muslim Ban”), on January 27, 2017, barring those from Iraq, Iran, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya, and Somalia from entering the United States.

The Thind decision, just six years after the 1917 Immigration Act, further suppressed the possibilities for the nascent South Asian American community. Not only did it prevent Thind and others from becoming U.S. citizens, but it also stripped citizenship from those who had already done so.

Whose Struggles Are Ours?

In 1930, a South Asian immigrant published a vicious letter in The Chicago Defender, penned under the name K. Romola, dismissing any possible solidarity between African Americans and South Asians: “Too much has been written by the Negro papers, magazines, and fourth rate writers like Du Bois, about the darker races,” he wrote, “but who in the hell wants to join the caravan with the black ones? Our caste system in India excludes those who do not belong to the Aryan (white) race and we even here exclude any Indians who live and socialize with the Negro.”

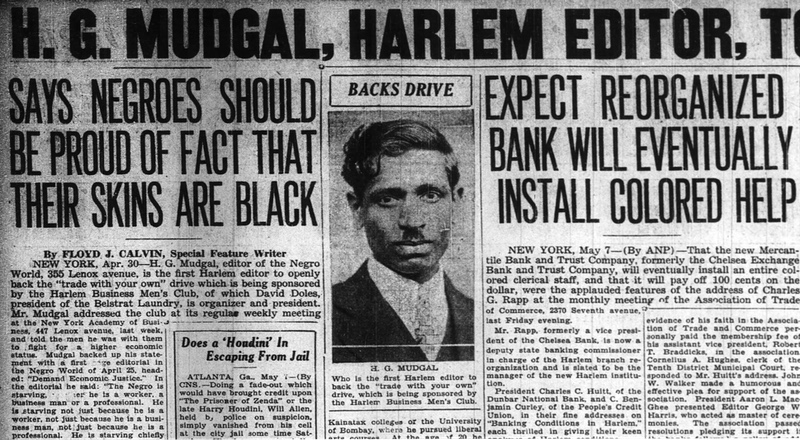

Hucheshwar Gurusidha Mudgal, a South Asian immigrant living in Harlem, wrote a scathing and ferocious response, describing his fellow Indian as an “out of touch” snob and self-hating “victim of the white propagandists.” Romola had “utterly forgotten the political, social, and economical oppression that India has been subjected to under the British,” Mudgal responded.

Mudgal’s life and political work was deeply invested in Black causes. Born in the city of Hubli, in what is now modern-day Karnataka, Mudgal arrived in New York around 1920. In 1922, he was hired to work for the Daily Negro Times and its successor the Negro World, both mouthpieces for the Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey and his organization the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). By May 1930, Mudgal had risen in the ranks, serving as an acting managing editor for the Negro World, a position he held until June 1932. Mudgal’s writing often stressed the interconnected nature of the African American struggle and worldwide anti-imperialist movements, including in India.

The question of whose struggles the South Asian American community chooses to identify with has echoed throughout its history. It was also evident seven years prior to Romola and Mudgal’s correspondence, in Bhagat Singh Thind’s argument to the Supreme Court. In making his case, Thind had argued that he should be allowed to retain his American citizenship because, as a “high caste Hindu of full Indian blood,” he actually belongs to the “Caucasian race.” He was therefore “white,” Thind claimed, and thus should be eligible for citizenship.

Thind was following in the logic of Takao Ozawa, a Japanese immigrant, who just a few months earlier had argued before the Supreme Court that his skin was just as white as the average white person, and therefore he too should be allowed to become an American citizen. Like Thind, Ozawa also lost his case in unanimous decision, because, as Justice George Sutherland concluded: “the term ‘white person’… is confined to persons of the Caucasian Race.” And Ozawa, having been born in Japan, was “clearly not a Caucasian.”

So that is where Thind began his argument, claiming that he was, in fact, “Caucasian,” because of the “purity of [his] Aryan blood” which, according to the outcome in the Ozawa decision, should allow him to become a citizen.

In his argument, Thind was attempting to use caste segregation as a way to claim racial purity. At one point, Thind’s petition describes how the “high-class Hindu regards the aboriginal Indian Mongoloid in the same manner as the American regards the Negro, speaking from a matrimonial standpoint.” In his claim to be “white,” “Aryan,” “Caucasian,” “high caste,” and “high class,” Thind was attempting to disassociate himself from categories that could be understood as non-white. Hence, he contrasts himself with the “aboriginal,” “Mongoloid,” and “negro,” categories that are unmistakably not white. As the scholar Sucheta Mazumdar has argued, such a claim constitutes a “racist response to racism.” It was also a casteist response to racism.

The justices again disagreed with Thind. This time because the word “Caucasian” was being used in a way differently from how it would be “interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man.”

As Ozawa and Thind both learned, there was nothing they could have said to convince the Supreme Court otherwise. The Court was not concerned about scientific analysis or legal arguments, but about the future of the country and what that future looked like. As Sutherland explained further:

“The children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian, and other European parentage, quickly merge into the mass of our population and lose the distinctive hallmarks of their European origin. On the other hand, it cannot be doubted that the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry. It is very far from our thought to suggest the slightest question of racial superiority or inferiority. What we suggest is merely racial difference, and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognizes it and rejects the thought of assimilation.”

A couple years later, John Mohammad Ali, a South Asian immigrant in Detroit also found himself at the receiving end of the same rejection. Wallace Visscher, the U.S. Attorney in Detroit, became aware that Ali had naturalized as an American citizen in 1921, and began challenging his citizenship in court. Distancing himself from Thind, Ali argued that, even though he was a native of India, his ancestors were Arabians, and based on previous court rulings where Indians claiming to be Afghani and Parsee were eligible for citizenship, he too should be accepted. His ancestors, Ali said, had “been careful not to intermarry with the ‘native stock of India'” and he even provided evidence in court linking his genealogy back thirty-one generations to the Prophet Mohammed himself. Ali lost as well, and his citizenship was cancelled by the court.

Embedded in both Thind and Ali’s arguments was a claim to “racial purity” that seems deeply abhorrent today. While critiquing the exclusionary sentiment of the time, Thind and Ali were simultaneously attempting to exploit existing prejudices that they thought would work in their favor. Thind, for example, was relying on the Court’s acceptance of him as a “high caste Hindu,” since the systemization of social hierarchy through caste was looked upon fondly in the United States, with some wealthy white men even going as far as calling themselves the “Boston Brahmins.”

As the Thind decision teaches us, the strategy of claiming whiteness, or using one’s religion, caste, gender, or wealth to appeal for acceptance, is ultimately a losing one. In fact, it was only in the 1960s, in the midst of the Civil Rights era led by Black Americans that South Asians were finally allowed to enter the United States in larger numbers.

And, like H.G. Mudgal, South Asians worldwide have been drawing inspiration from, and collaborating with Black Americans’ fight for freedom and justice for centuries. In 1873, Jotirao Phule, a social reformer in Maharashtra, India began his essay Gulamgiri (Slavery), with a dedication to American abolitionists. And in 1971, a group called the “Dalit Panthers” in India declared in their manifesto: “From the Black Panthers, Black Power was established. We claim a close relationship with this struggle.”

________________________

Courtesy: South Asian American Digital Archive

Also read the Guardian report on American Racism