In 2022 alone, several directors were summoned by the Iranian judiciary and in May, dozens of documentary filmmakers were arrested and subsequently released, for reasons never fully disclosed.

By Joseph Fahim in Venice, Italy

In any given year, a strong showing for Iranian cinema at one of the world’s biggest film fairs would have been cause for celebration. In Venice, however, the prizes and rave reviews that greeted this year’s lineup felt bittersweet.

Iranian authorities and filmmakers have been in a tiptoe game for decades with the level of censorship determined by each new government.

A year into the reign of ultra-conservative president Ebrahim Raisi, filmmakers find themselves under a kind of scrutiny not seen since the days of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

In 2022 alone, several directors were summoned by the Iranian judiciary and in May, dozens of documentary filmmakers were arrested and subsequently released, for reasons never fully disclosed.

Mostafa Aleahmad and Berlin Golden Bear winner Mohammad Rasoulof, who was already stamped with a one-year jail sentence in 2020, were arrested in July in connection with protests that followed a deadly building collapse in the city of Abadan.

Until Raisi completes his four-year term, Iranian cinema appears to be heading into a fresh wave of repression. Given that context, the large Iranian offering at Venice – four films in the official selection and a documentary in the Venice Days sidebar – was all the more remarkable.

More startling was the anti-authoritarian charge of these films, traversing themes from police brutality to patriarchal oppression and class antagonism.

Panahi’s Meta reflection on the purpose of filmmaking

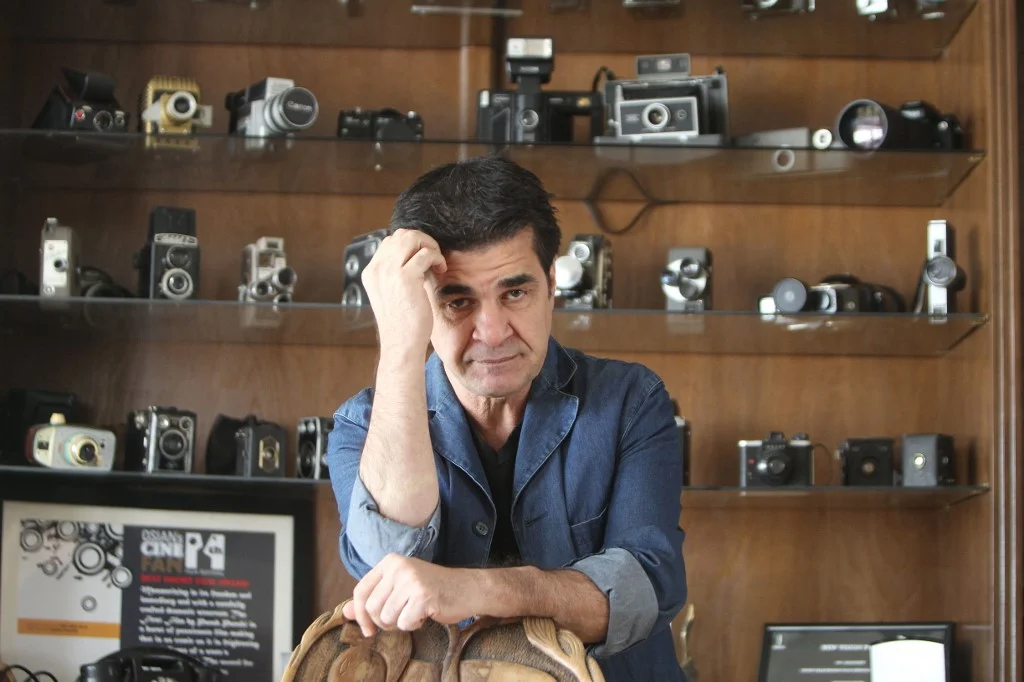

Sentenced to six years in prison in July, 62-year-old director Jafar Panahi’s latest effort, No Bears, drew most buzz from the Iranian selection and should remain a fixture in international art house cinemas for the next year after earning the Special Jury Prize at the festival.

The director is front and center of the self-referential film, playing himself as he directs a docu-fiction account of a dissident couple trying to flee to their provisional Turkish stopover before heading to Europe.

Having been banned from travelling by Iranian officials after his first prison sentence in 2010, Panahi took a temporary residence in a village near the border to be close to the shooting location.

As the couple questions the worth and objective of the entire enterprise, Panahi finds himself in hot water with the villagers when he accidently shoots a young bride-to-be with a man who is not her fiancé.

Several meta narratives unfold, culminating in the director’s most devastating conclusion since 2006’s Offside.

Panahi has continuously turned the camera on himself since 2010 in a fashion absent from the previous work. His post-incarceration output is essentially one long act of defiance against a system that has treated him as a public enemy for much of his career.

With No Bears, Panahi reaches the point of self-reckoning, questioning the social validity of his work and confronting the limitations of art.

The dissident couple gradually rebel against their director who never explains why he needs to tell this specific story. Who is it for? What is its purpose? Could this just be an act of self-validation? Or perhaps a distraction from a situation where nothing changes?

The photos Panahi takes by accident further augment the question of responsibility in his image-making.

Even the village is no random choice and serves as a microcosm of small-town Iran, a place Panahi quixotically craved to change but never will.

No Bears is the brave work of a jaded artist at another major crossroads. Nevertheless, this is not Panahi’s strongest effort aesthetically speaking, as excessive dialogue and myriad plotting results in mostly flat imagery.

The intended poetry and mischievousness is only glimpsed here with ideas rarely finding an equally potent visual translation.

Still, the film remains another stepping stone in one of the most unusual careers of all Iranian filmmakers. At one point during the film, the viewer is struck by the severity of Panahi’s condition, by his debilitating captivity – a man who has been involuntarily stuck in one place for 12 years now.

Even more distressing is the reality that given his recent prison sentence, this could be Panahi’s last film in quite a while.

World War III and cinema’s detachment from society

Another film questioning the ethics of filmmaking is Houman Seyyedi’s World War III, winner of best film and best actor for Mohsen Tanabandeh at the Horizons competition at Venice.

Tanabandeh plays Shakib, a down on his luck middle-aged man who lost his wife and child in an earthquake. The uneducated Shakib finds himself as an extra in a shabby period pic about the Holocaust, before he is haphazardly promoted to play the lead, Adolf Hitler, after the original actor falls sick.

Shakib falls for a deaf sex worker who soon lodges with him at the mansion set he’s been allowed to stay in during production.

Things start to spiral out of control as blackmail and a freakish accident transform the meek Shakib into a monster. The unnerving conclusion is among the most violent endings this writer has seen in an Iranian film.

Starting off as an uproarious black comedy then evolving into acerbic tragedy, World War III is, by turns, a character study, an examination of destructive class disjunction, a highly intense anecdote of scorching love, and a parody of commercial Iranian filmmaking. These myriad strands are adroitly weaved into a relentless drama that never loosens its grip on the viewer.

Even before verifying their intentions, Shakib shows a palpable distrust towards the filmmakers, subliminally casting himself in the role of hapless working-class victim exploited by the rich artists’ class.

In that sense, World War III – Iran’s official submission to next year’s Academy Awards – is a parable of how ignorance and economic deprivation can form the basis for great if unintentional evil.

Seyyedi, a commercial filmmaker himself, nods to a mainstream cinema utterly dissociated from reality and ordinary people.

Without Her and class privilege

World War III is co-written by Arian Vazirdaftari whose directorial debut feature, Without Her, was easily the best of the Iranian selection.

Tannaz Tabatabaei is Roya, an upper middle-class woman preparing to immigrate to Denmark. Almost out of nowhere, she stumbles upon a young woman who cannot remember who she is. Roya takes her in and before long, the young woman steadily begins to take on her identity as the line between reality and hallucination gradually blurs.

Without Her starts off as a run-of-the-mill domestic drama about a privileged couple confronted by serious moral issues: Roya must inform on colleagues if she is to receive travel authorization from Iranian officials.

When Roya’s eye surgery strikes her with cryptic blackouts, the film swiftly turns into a Brian De Palma-like pulp noir about the slipperiness of identity, suburban ennui and suppressed womanhood.

That radical shift in genre and perspective is mirrored in Tabatabaei’s cunning visuals. The staid, near-monotonic look of the first half gives way to distorted lighting and frantic camera movement as Roya’s paranoia intensifies.

Crowned with a brilliant twist ending, Without Her is a superior genre pic constructed on the enduring relation between class and the space given to Iranian women for self-actualization.

Beyond the Wall on police brutality

Another title sporting a major twist ending but without the thoughtfulness or skill of Tabatabaei’s is Vahid Jalilvand’s competition entry Beyond the Wall, an on-the-nose study of trauma that nonetheless touches upon the most pertinent topic in Iran today: police brutality.

Near-blind Ali (Navid Mohammadzadeh) is a thirty-something man on the verge of killing himself. His plans get disrupted when young mother Leila (Diana Habibi) covertly slips into his apartment.

Leila has lost her son during a workers’ strike and has been blamed for the accidental death of a police officer who was killed in a bus crash. Ali agrees to shelter Leila as the police survey the city for the fugitive woman. In little time, he grows attached to Leila, but things may not look as they seem.

For the larger part of the film, a shell-shocked Ali spends most of his time brooding over his cruel fate while fending off the invasive police keeping him under surveillance.

Leila, meanwhile, is either screaming or sulking as she attempts to find the whereabouts of her missing son who has Down’s syndrome.

The claustrophobic setting amplifies Ali’s confinement, but his real affliction is only revealed with the twist ending, which lends the picture a much needed, if belated, vitality.

That said, ultimately it comes off as a gimmick rather than a genuine reveal.

Jalilvand attempts to evoke Ali’s trauma via a chamber piece structure that grows increasingly stagnant in the last half hour (the film is 124 minutes long).

Bafflingly thin on characterization, the lack of sympathy for these awfully one-dimensional characters is augmented by Mohammadzadeh’s irritatingly one-noted self-important performance and Habibi’s lack of range.

The politics of the narrative is inarguably far more engrossing than the actual film.

Surveillance is not the main theme of the picture, which is utterly ruined by the ending, but police violence and systemic injustice are framed as the main unquestionable culprit.

The chaos Ali and Leila are thrust into is exposed as the byproduct of an apathetic, aggressive police enforcement hellbent on squashing any rightful dissent by any means necessary.

The scenes involving police mistreatment of protesters feel eerily similar to the current Mahsa Amini demonstrations – enough of a reason for the film to face a potential ban in Iran.

Anti-police sentiment is certainly the most important asset of the film, providing a strong emotional charge that carries the story in many of its redundant moments.

Alas, Beyond the Wall is ultimately failed by a misshapen and contrived narrative that dilutes its otherwise urgent and topical theme.

No Bears is screening next month at the New York Film Festival and BFI’s London Film Festival.

__________________

Courtesy: Middle East Eye (Published on 23 September 2022)