To label us “brave” is to fight your battles from our shoulders. The burden of bearing witness and speaking truth to power comes at great personal risk for journalists in many countries around the world.

Rana Ayyub

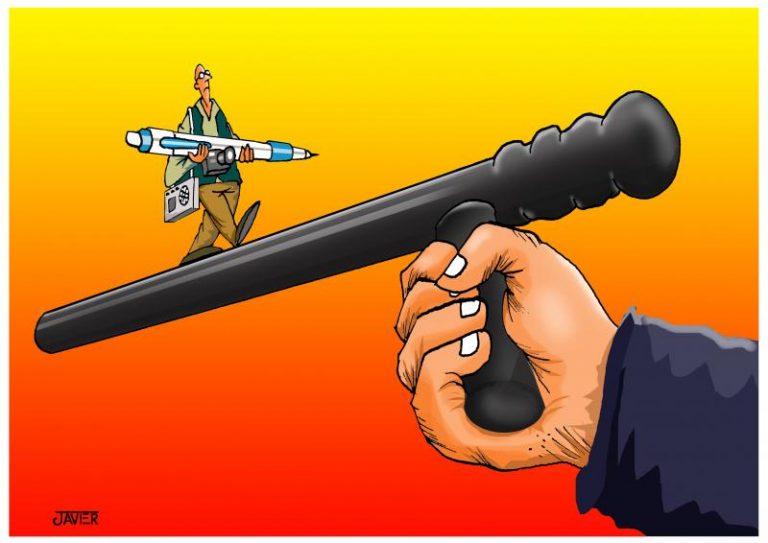

The stereotype of the “brave journalist”, or the “courageous journalist” has been troubling me for a while. To label us “brave” is to fight your battles from our shoulders. The burden of bearing witness and speaking truth to power comes at great personal risk for journalists in many countries around the world. They live a relentless struggle, slapped with lawsuits and criminal cases for sedition, defamation, tax evasion and more. Their lives, and too often the lives of their families, are made miserable. This World Press Freedom Day, consider the toll it takes on them not only to be journalists, but also to be “brave”.

When a journalist is killed or incarcerated or assassinated, obituaries scream bravado, editorials claim courage. Have such plaudits normalized the persecution of journalists? Why does a journalist have to be brave to report facts as they are? Why does she need to be persecuted for her story to reach the world? Consider Gauri Lankesh, Daphne Caruana Galizia and Jamal Khashoggi—all journalists with a profile, all brazenly killed in broad daylight. Their murders dominated the front pages of international publications. But their killers, men in power, remain unquestioned not just by the authorities but often by publishers and editors who develop a comfortable amnesia when meeting those in power. They do not want to lose access to them.

The very world leaders who ignore the persecution of journalists in the largest democracies are often seen lighting candles in honor of the persecuted—the slain journalists in whose memory prizes will be awarded. The vicious cycle will continue with no course correction.

Journalists are the new enemy of the state; we are going through one of the toughest phases in the history of the profession. We document the truth at a time marked both by a voracious demand for news and by the persecution of minorities, genocide and war crimes. We witness savage attacks on minorities in India, Myanmar, China, Palestine or Ukraine even as bumbling editors still frame arguments and narratives through the prism of “‘both sides”. For example attacks on Palestinians, even during Ramadan, are often referred to as “clashes”. Despite one side having grenades thrown at them, and pelting stones in defense, the lens of the mainstream media remains firmly aligned with the oppressor. In India attacks on Muslims by Hindu nationalists often are reported as “riots” or “clashes”, too. The distinction between oppressor and oppressed can be blurred as convenient.

I have myself received awards for bravery and courage. I have even delivered speeches with titles such as “Courage under fire”. Over the past year I have been inflicted with death by a thousand cuts. I have not been physically harmed (small mercies). But since I wrote a cover story for Time magazine in May 2021—in which I held India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, accountable for millions of deaths through a devastating second wave of covid-19—my life has been made miserable. My bank accounts have been frozen, apparently because they contain the “‘proceeds of crime”. Cases are proceeding against me for a social-media post about a hate crime against a Muslim man. Another case has been registered for a statement I made about Hindu nationalists on a BBC program. And last month, as I tried to board a plane to the United States to receive the Overseas Press Club of America Award, a missive from India’s home ministry asked me for information about an alleged violation relating to my receiving foreign currency.

This all comes after a campaign to discredit my character. I’ve been attacked on national television by journalists and editors and seen a pornographic video with my image morphed on it spread across social media. As somebody who has been relentlessly subjected to the worst kind of offline and online harassment for over a decade, the past year has been a living, breathing nightmare. I did not sign up for this kind of treatment when I decided to be a journalist.

Maria Ressa, the Nobel peace-prize laureate, has been fighting state-enabled persecution in the Philippines for years. She has to take court orders to fly out of the country. Both Ms. Ressa and I have access to great lawyers. We have a public profile, a huge social-media presence, helpful editors and privilege which many unsung journalists in the world are not accorded. The unsung are murdered and incarcerated with impunity and in anonymity. Take my colleague, Siddique Kappan. He has been incarcerated for the past two years by the Uttar Pradesh police. He was stopped while he was on the way to report the gang rape of a lower-caste girl. He was arrested before he’d even had a chance to report and write.

How do journalists fight this battle? They want to report with integrity without paying a price for their dedication. Prejudice towards journalists from poor communities, towards journalists of color and towards women in the profession is obvious. Their stories of the persecuted demand empathy and not neutrality. Media outlets need to hire more women journalists, we need to see more Muslims, dalits and people of color on our screens and in our bylines, a diversity that is missing from the media culture. We need to protect our journalists by giving them the best legal support. They also need to be provided with the best mental-health care and therapy. I am speaking from experience. Had I not received the kind of support I did from my editors at the Washington Post, from various media-protection organizations, advocates of free speech and a dedicated therapist, I would have crumbled long ago.

Journalism was never a nine-to-five profession. We knew it was an unconventional calling, and one where we might not leave the office for days, or where our families might have no communication from us as we report on crucial investigations, wars and undercover operations. Journalism schools taught us the ethics of our profession, but they did not warn us about nervous breakdowns, or about spending more time in courtrooms than newsrooms. We owe it to the next generation of journalists to create a safer environment in which to work. They should fear only the distortion of truth, never reporting the truth itself.

___________________

Rana Ayyub is an Indian journalist.

(The article received through email. It was originally published in The Economist)