Mangal Singh’s tale finds an intriguing parallel in the world of pahalvani that thrived in colonial Lahore. In 1910, a gifted young wrestler named Manni Reniwala collapsed after a ferocious bout against the dreaded Kala Partapa. His promising career, nurtured under the tutelage of the famed Buta Pahalwan, was cut short, and he passed away from a cerebral hemmorhage. It was said he had produced such a cataclysmic, singularly powerful expenditure of energy that his liver exploded under its strain. The liver (ਕਲੇਜਾ ‘kalejaa’), it must be noted, is considered the subtle seat of vitality and emotion in Punjabi cosmology.

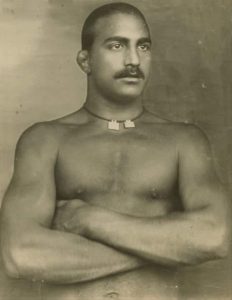

MAHĀVĪRA SIṄGH

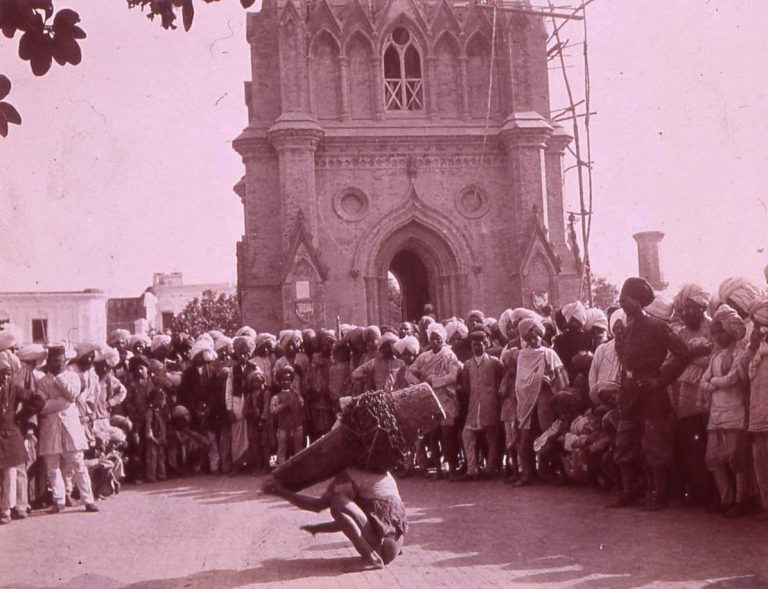

The wrestling arena was thronged with visitors attending the vaisakhi fair at Dera Baba Nanak. Colorful turbans seemed to present a vivid map of some springtime orchard. Flaunting bludgeons, hatchets, pikes, long axes, men youthful, middle-aged and elderly all stood together, laved with perspiration, their eyes keenly following the young man pacing about the arena. A full six feet tall, physique unblemished, burly like a bull’s, his face too was exceedingly fetching. He sported red underpants, scrunched between his thighs, on his topknot a red kerchief.

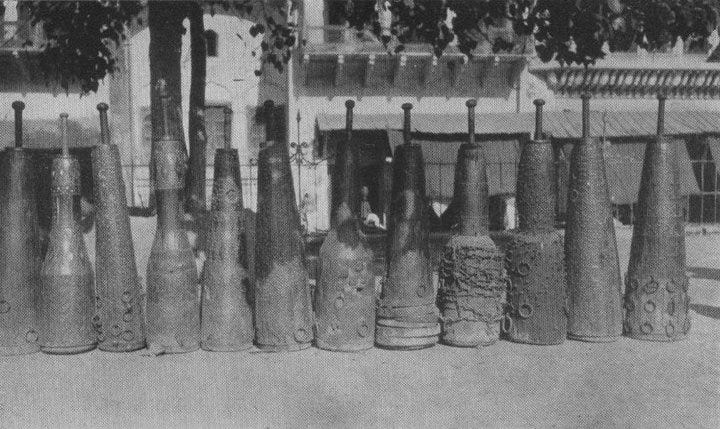

A bludgeon stood firmly planted in the middle of the arena. From it hung a soft rose-hued turban. A kerchief was tied to it as well, with a thousand rupees inside. Right next to it lay a heavy black-colored mace: embedded with nose-pins, tethered to iron spikes hammered into the ground.

After striding all over the arena, the youth came to a halt next to this mace. He touched his ears and evoked his saintly pir. Then, swinging the mace over his head, he brought it to the ground.

He stood up to steady his breath, his well-oiled body glistening like a bowl of bronze under the late afternoon sun. As the drummer beat his dhol with a stick, the young man began idly ambling around the mace, as if drying his sweat.

A compere, scarf wrapped over his head, cane in hand, pushed the rabble back to clear up space. He stood next to the mace and motioned to the drummer to stop. Once the drumming stopped, the compere raised the arm holding a cane, and spoke to the crowd, “Brothers! This mace-bearing young man here has come from the princely state of Kapurthala. He declares that the man who can swing this mace will be awarded a thousand rupees. One thousand.” He touched the kerchief tied to the turban and added, “Fifty-twenty rupees!”

The compere finished his announcement. The drummer resumed beating his drum. The people broke into a purling chatter, their eyes glued to the strongman and his mace. Outside the arena, horsemen stood up on their horses’ stirrups to look. The young fellow with the mace looked round at the crowd that stood about him one more time, and then stepped away from the mace.

Amongst the crowd in the arena were those who had travelled from afar: wrestlers, kabaddi-playing sturdy young men, robust lifters known for hefting heavy objects. And yet, it seemed as if none standing in that arena could muster the courage to lift the mace. The mace-bearing strongman cocked his neck like a rooster yet again, eyeballing the gathering, as if to taunt them, “Is that all, boys?”

The aging Mangal Singh, standing on his horse, had been watching this unfold with his friend Banta Singh. He fastened the tail of his turban garlanding his neck over his head, and with a long-axe in the other hand, took hold of the horse’s reins. Standing on the stirrups, with a booming voice, he derided the men standing in the arena, “Woe upon such youth, you great heroes! Go ahead, someone grab hold of that mace.”

He turned to Banta Singh and exclaimed, “Look at these boys: they’ve been bred and trained like bulls, and yet they’re all hollow on the inside, hollow. They’re all degenerate, not one of them has any blessed vitality left in them.” Mangal Singh seemed to be animated with an extraordinary fervor. Banta Singh laughed at his words, but did not say anything.

The whole arena turned to behold Mangal Singh. Many felt insulted by his comment, but none dared respond in kind.

Mangal Singh had given up banditry a long time ago, yes, but he was always ready for a bloody fight. Perhaps due to this fearsome reputation, or on account of his declining eld, he had come to command a certain esteem. He had long crossed fifty years of age, and his beard had turned white as well. To someone who regarded him the first time, he would appear but an old man possessed of middling height and sinewy frame.

Mangal Singh stood up on the stirrups yet again, and yet again he challenged the youth, “Rouse yourselves, lads. He who lifts and swings this mace, I promise to buy him ghee worth two paisas.”

Their pride stirred by Mangal Singh’s louring taunts, five men, renowned for their strength, entered the arena. But the mace would not wield, and they departed after struggling in vain, hiding their faces in humiliation. Mangal Singh almost fell off his saddle in an impassioned fit of rage.

Meanwhile, Mangal’s son Jangal Singh had walked into the arena, securing his loincloth. To descry his son in the arena brought a glint to Mangal Singh’s eyes. He commanded, “Be strong now, Jangal! Today you prove the worth of my upbringing through and through.”

Jangal Singh was an exceptionally strapping young man. There was none in the area who could match him in lifting the heaviest of weights. Being an only son, he had been brought up by Mangal Singh with much enthusiasm.

Jangal Singh went straight to the mace and grabbed hold of it. People watched with their eyes peeled. Jangal Singh cried out ‘Waheguru’ and threw his weight into the hefty upheave: he lifted the mace up and gripped it in his hands and swung it over his head.

But as it passed behind him, the mace’s careening momentum exceeded his grasp. It fell to the ground, smashing into his heel. Blood sprang from his cleaved heel as if from a fountain.

Mangal Singh felt no regret over this injury: much graver were the wounds he now bore of disgrace and shame. “What is left to say, brother!” he wondered, watching the earth dampen with blood.

Standing close to Mangal Singh, Banta Singh swiftly jumped off his horse. He hurried into the arena, piercing through the crowd. He kneeled and checked the wound on Jangal’s heel. From within the knotted hem of his chaadar, he pulled out a bottle of alcohol and poured it over the wound. He tore a length of cloth from the turban on his shoulder, doused it in the alcohol and wrapped it around the heel. Tying the turban on his head again, he slapped Jangal on the back and said, “God’s mercy, son! No matter… lifting a mace is a matter of strength. To swing it, however, demands skill, and you had never swung a mace before.”

Jangal did not utter a word, and limped out of the arena holding onto Banta Singh’s shoulder.

Mangal Singh observed all of this with a preternatural calm. The mace-bearing strongman looked around at the spectators again— but they had been struck dumb. Mangal Singh gently dismounted from his horse. He held the long axe aloft firmly in his hand as he stepped into the arena.

The mass of people was hewn in two! They cleared afore his path, parting like the sea’s waves. Once inside the arena, Mangal Singh struck an imperious pose. He glared at the mace-bearing strongman.

The spectators held their breath. In that moment, everyone knew in their hearts: this young strongman’s luck had finally run out.

But Mangal Singh said nothing to the strongman, not a word. His gaze bore into the mace. He circled around it once. He placed his long axe on the ground and removed his shoes, then took off his turban and hung it on the prized bludgeon. He fastened his chaadar around his loins, and went up to the mace.

He grasped the mace. In the tensioned silence that encased the arena, one could hear the stunned crowd draw bated breath. The young strongman burst into laughter at the sight of this slightly built man, and took an amused step back, crossing his arms across his chest, fists tucked into armpits.

Mangal Singh gave the cry of ‘Yaa Ali,’ and lifted the mace and held it upright in his hands. His veins flared up, bulging, ready to rupture. His eyes steadily followed the mace held arrect in the air. Rolling the mace in his hands, he deftly assessed its weight and swung it over and behind his head.

A perfect swing— a second — a third.

He swung the heavy mace with the finesse of a gatka master brandishing his cane. The onlookers stood stupefied, turned into stone-fashioned idols. The strongman too could do little but stare at Mangal Singh in disbelief. It was as if Mangal Singh had gone mad.

He kept swinging the mace over his head.

At last, he gained control of the mace and nimbly brought it to a halt on the ground.

His steps unsteady, he staggered towards the prized bludgeon. He caught hold of it, but before he could wrench this bludgeon out of the ground, he collapsed on the ground like a tree severed.

The prized bludgeon was firmly clasped in the fist of the dead Mangal Singh.

___________________

Afzal Ahsan Randhawa (1937-2017) was an eminent Pakistani Punjabi poet and novelist, a towering figure in modern Punjabi literature. Born in Amritsar, he considered himself a sehajdhari Sikh, and sought to promote Punjab’s cultural heritage (one he was born into and molded by, and continued to cherish) through his work.

Afzal Ahsan Randhawa (1937-2017) was an eminent Pakistani Punjabi poet and novelist, a towering figure in modern Punjabi literature. Born in Amritsar, he considered himself a sehajdhari Sikh, and sought to promote Punjab’s cultural heritage (one he was born into and molded by, and continued to cherish) through his work.

He chose to write in Punjabi at a time when the language was deemed ‘coarse’ and ‘seditious’ in Pakistan’s literary circles. His works and interviews reveal a worldview shot through with the layered idioms and archetypes of Punjabi society. He brought to life that world of heroes and rebels, vengeance and honor, rural customs and domestic intrigues, clans and kinship networks: a literary cosmos at once laconic and poetic, brutal and poignant, operating in the interpenetrating folk and epic temporalities that inform all great Punjabi literature.

Courtesy: The Khalsa Chronicle (Received through email on February 26, 2023)