I grew up in an extravaganza of colors — embroidered Kashmiri carpets, textiles from Swat and Sindh and Rajasthan, striking Punjabi shawls, brightly lacquered chairs, mirrored embroideries, the colors of turmeric and turquoise and mango – Hazel Kahan writes in her book ‘A House in Lahore’.

Beth Young

Mattituck resident Hazel Kahan, a radio host on the independent station 89.5 WPKN, has devoted herself for years to exploring the lives of North Forkers through her program North Fork Works. Her wide ranging interviews often come home to a discussion on how her subjects conceptualize home and belonging and finding one’s place in the world.

This fall, she’s turned the lens onto herself, exploring her own unique place in the world in a memoir, “A House in Lahore: Growing Up Jewish in Pakistan,” about her childhood as the daughter of Jewish doctors from Europe who’d sought safety in what was then India and is now Pakistan during the trauma of the Second World War.

The memoir, which she wrote mostly over the past two years, is alive with recollections cemented in a childhood filled with far-from-everyday occurrences, as she tries to understand her family’s unique place in the world.

“I grew up in an extravaganza of colors — embroidered Kashmiri carpets, textiles from Swat and Sindh and Rajasthan, striking Punjabi shawls, brightly lacquered chairs, mirrored embroideries, the colors of turmeric and turquoise and mango,” she writes in a story rich with precise memories of the place she called home as a child.

Ms. Kahan’s sense of statelessness is a multigenerational one, borne out of a multitude of shifting national boundaries, many the result of the World Wars of the early 20th Century.

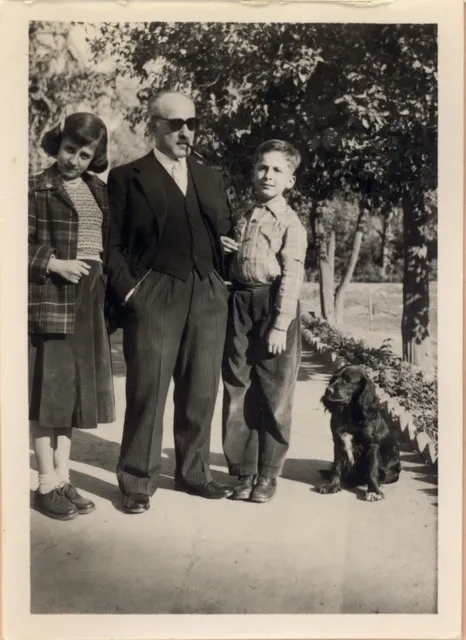

Her mother and father, Kate and Hermann Selzer, both of Jewish descent, met in Berlin in 1932 when they were medical students. Her mother was born in a part of Pomerania that was once Germany and has since become part of Poland, while her father was born in a part of the Austro-Hungarian that became part of the Russian Empire and then Poland, and is now in Ukraine. Kate was a German citizen until she married Hermann and became a Polish citizen.

But “neither of them spoke Polish nor did they know anything much about being Polish,” said Ms. Kahan. The Polish government stripped them of their passports, because they were not culturally Polish, as the Second World War began in 1939.

Both had been studying to become doctors in Germany when Jews were no longer allowed to study medicine in 1933. But they didn’t strike up a relationship until they met again as medical students in Rome in 1933, where they’d both uprooted to continue their studies. He moved to Lahore, then in India, in the hopes the distance would insulate them from the rise in anti-Semitism in Europe, and then asked Kate, who was finishing her medical studies in Rome, to join him. They started their family in Lahore.

But while they escaped fascism, the Indian government, then under British colonial rule, placed her family in an internment camp in 1940 after they’d been stripped of their Polish passports. Hazel was just shy of her second birthday on the December day when two policemen arrived on their doorstep to transport them to the first of two internment camps. Her brother, Michael, was just seven weeks old. Her memories of the camps are spartan and cold but not cruel — the people who had imprisoned her parents understood they were not enemy combatants, and their medical skills were in high demand in the camps.

After emerging from the war, her parents built their medical practice in earnest, and the young family remained insulated in the cosmopolitan city from the bloody 1947 upheaval of the partition of India and Pakistan. Ms. Kahan was born on the eve of war in the Lahore of India, and left home as a teenage boarding school student with a British passport.

A passport was something her parents had been denied for much of her childhood, and Ms. Kahan had always felt the need to have her passport close at hand. She learned years later from reading her father’s unpublished 370-page manuscript, “written in German, bound with two unmatched pieces of striped cotton, the punched pages held together by shoelaces,” that she was not alone in her family’s desire to always know where her passport is.

A passport “is a document which proves to the world, and ultimately to yourself, that you exist, that you are legally a person,” her father wrote. “It provides you with a fatherland. It informs the holder and the viewer that whoever maltreats you can count on one day being paid back for his behavior. It guarantees to all concerned that you have a home to return to.”

“A man without a passport is not a man,” he later told her, when he was an old man living out his remaining years in Jerusalem, where her parents later joined other family members who had chosen to flee to Palestine instead of India during World War II.

Ms. Kahan, who had married an American and worked in market research in this country for 25 years before retiring to the North Fork, didn’t return to Pakistan for much of her adult life, but she held the richness of her memories of those years close to her heart. In 2011, she resolved that she would find her way back home, and hopefully see the house she’d lived in as a child.

While Ms. Kahan hadn’t felt singled out for being Jewish during her childhood in Lahore — she had envisioned her family as a sort of archetypical group of wandering Jews who, while stateless, were also at home as citizens of the world, she said the post-war founding of the State of Israel had changed Pakistani attitudes toward Jews, ultimately leading her parents to leave.

“They say that Pakistanis are intolerant of minorities, but I didn’t feel that at all growing up in Lahore,” she said. “It was known as a cosmopolitan place, off the Silk Route. The politics came in after partition, when the Saudis began putting money into madrassas [Islamic schools].”

She added that the government of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto had conflated Jewish people with Zionists, but that attitudes toward Jews there began to soften when British journalist Jemima Goldsmith, who is of Jewish descent, became a folk hero when she married Imran Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan from 2018 until April of 2022, and converted to Islam, living in Lahore and embracing the culture there.

This January, Ms. Kahan has again been invited to Lahore, where Najam Sethi, a Pakistani journalist and founder of the publishing house Vanguard Books, has agreed to publish Ms. Kahan’s book in Pakistan, where books are still a burgeoning business.

But she has no illusions that Lahore is still her home. That home exists in her memoir now, more than it does in the physical world that now surrounds us.

“I don’t feel it as a loss. I’m not a member of anything,” she said of her enduring sense of statelessness. “I don’t understand what it would feel like to be a member of a group. I feel more freedom than I do loss. I feel perfectly comfortable in this country, and I feel it is comforting to me to be in Lahore. But I do worry now about anti-Semitism in this country.”

“A House in Lahore” can be purchased on Amazon, and you can read more about Ms. Kahan’s work at hazelkahan.com.

_____________________

Courtesy: East End Beacon (Published on January 6, 2023)