During her stay in the region, Marianne was a regular visitor to the palace of the Rao of Kutch. She drew a sketch of the Rao and her writing suggests that she was particularly fond of the young ruler.

Ajay Kamalakaran

On a pleasant January morning in 1834, a few officers of the 15th Regiment of the Bombay Native Infantry, along with their spouses, set sail from Bombay for Kutch on a kotiya, a large wooden trading dhow. Among them was a young couple that was happy to live in Bombay. Thomas Postans, a 26-year old junior officer, had married his wife Marianne a year earlier, before talking up a position with the Bombay Army. Marianne, then 23, was passionate about drawing and writing. She began documenting her impressions of life in India almost immediately after leaving Bombay. Her sketches and notes were published in 1839 in the form of a book titled Cutch or Random Sketches Taken During a Residence in one of the Northern Provinces of Western India.

“Few persons can leave Bombay without regret,” Marianne wrote. “Its lovely scenery, hospitable society, and its civilized condition cannot but charm the English visitor; and when duty commands that he should resign its pleasures, the voyager does so with a sigh, and his boat recedes from the shore, and the gay tents on the esplanade dwindle to mere specks, full many a wistful glance does he cast back to the distant scene of life and enjoyment.”

The journey from Bombay was tedious. Marianne wrote about the lack of hygiene on board the kotiya, calling it a scene of “filth and confusion”. It must have been a relief for the passengers when, a few days later, the dhow arrived at Mandvi, a bustling port that was the summer resort of the rulers of Kutch. Kutch had a sizeable British military presence back then, a result of it coming under British suzerainty in 1819.

Mandvi impressed Marianne immediately. “On approaching the province of Cutch, the coast affords few attractions to the traveler’s eye, presenting as it does, a mere sandy outline, slightly diversified by a few patches of stunted vegetation, and straggling palm trees; but on landing at Mandavie, which is the principal sea-port, an appearance of wealth and unusual bustle excites the traveler’s attention,” she wrote. She also seemed to like the people of the town: “The inhabitants seem a busy, cheerful, and industrious race, and their peculiarly bright and varied costume gives an appearance of gaiety to the place, which is strikingly pleasing and seldom seen in an Indian town of second rate importance.”

From the English writer’s note it is clear that the town was a major shipbuilding center at the time and the port was busy handling ships from Red Sea ports, Ceylon, eastern Africa and China. While cotton was the main export product at the port, items from far-flung places – such as African ivory, Arab dates and coffee and colorful mats – were being imported in large quantities.

Marianne noticed many Arab mariners in Mandvi: “The Arab sailors, who, coming from Mocha and other ports of the Red Sea, are frequently seen here, are a wild and singularly picturesque looking race; and although wearing the flowing robe, and graceful turban, common in the East, seem strikingly dissimilar to men of other tribes.” She wrote of their darker clothes and their pale blue and red turbans that were less studiously arranged than those of Indians. “Their general bearing is that of men used to peril, but accustomed to defy it,” she said admiringly.

Marianne wrote of two- and three-storied houses with terraced roofs and rich carvings, but added that Mandvi’s streets were narrow, dusty, ill-ordered and swarming with “Pariah” dogs and bulls that were fed by grain merchants. As in most towns in Indian princely states, the grandest structure was the ruler’s palace. Marianne called it the most strikingly curious object in Mandvi and said it was “most grotesquely ornamented by a variety of carvings, of dancing girls, tigers, and roystering-looking Dutch knaves”. The locals told her the palace was designed by a native of Khatiawar who was kidnapped as a child and taken to Holland.

Young ruler

During her stay in the region, Marianne was a regular visitor to the palace of the Rao of Kutch. “It is a large white stone building, decorated with beautiful carvings, and fine fretwork, in the same style as the ornaments of the palace at Mandavie,” she wrote. The inner passages and gateways were manned by Arab guards.

She drew a sketch of the Rao and her writing suggests that she was particularly fond of the young ruler. “The present Prince Rao Daisuljee (Deshalji II) is not more than twenty two years of age, having been elected on the formal deposition of his father, Rao Bharmuljee (Bharmalji), a prince long rendered infamous by his public and private crimes,” Marianne wrote. “The manners of the young Rao are peculiarly urbane and amiable; the personal attachment of his dependents is a proof of his benevolence and kindness of disposition; and the respect he observes in public towards his unhappy father, evinces the delicacy and tenderness of his character.”

It was the British who had overthrown Rao Bharmalji after attacking Bhuj in 1819. As expected, the writer believed the British presence in Kutch and the placing of Deshalji on the throne was for the greater good. “During the present reign, Cutch has regained its early tranquility and the country, from having been ravaged by freebooters and outlaws, is restored to the enjoyment of a legitimate and peaceful government.”

The British initially tried to get Deshalji to learn English and study sciences, but the Jadeja Rajput chiefs who helped put him in power in place of his father insisted that the minor’s attention be on governance. In reality, the kingdom was being run by a council of regents headed by an English captain until Deshalji became an adult.

Marianne wrote that Deshalji’s mother was a “devout supporter of the Brahminical creed” and she had succeeded in “imbuing his mind with the darkest superstitions of his people”. The Englishwoman added, “The population of Cutch, however, being composed of nearly an equal proportion of Mahomedans and Hindus, the interests of his government require that he should conform in public to both these forms of worship; but it is probable that he retains only a heartfelt respect for that religion, whose tenets are identified with the affections and associations of his childhood.”

Religion and pilgrimages

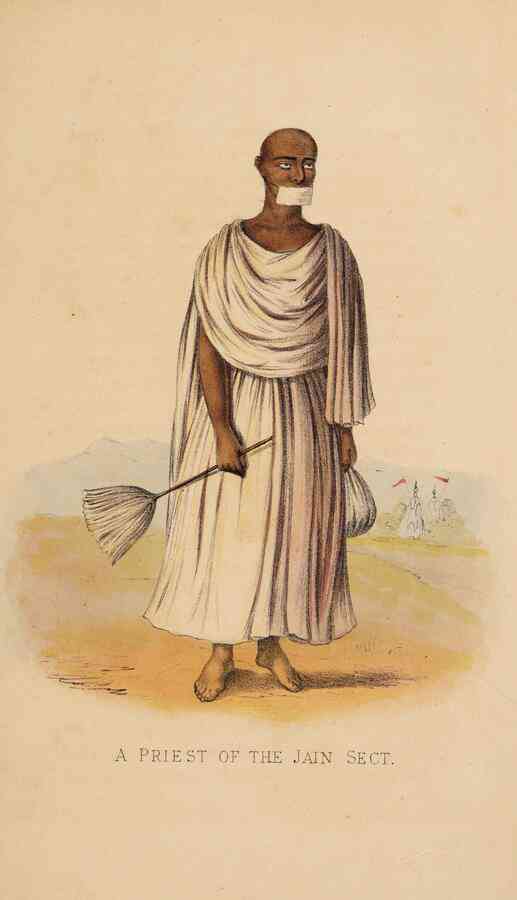

Given the British public knew very little about India in the early 19th century, Marianne went into great detail when describing religious practices and popular beliefs. From her book it appears that she was genuinely keen on observing pilgrims and pilgrimages.

“Hindu pilgrims are very numerous,” she wrote. “They come from the distant parts of India to perform penances at D’waka and at other places which bear a holy character.” Tanks, rivers, caves and forests were sacred for Hindus, Marianne wrote, but not as important as temples. “Immediately within reach of the devotees of Cutch is the temple of D’waka and that of Hinglag in Sindh.”

She noted that Kutch was a major transit point for Mecca-bound Muslim pilgrims from Sindh, Kandahar and Kabul. The Rao of Kutch allowed the pilgrims to pass through his territory to Mandvi, from where there would board dhows for West Asia. “Many of these poor fanatics perish on the way, from fatigue, climate and privation, combined with the effect of pestilential disease, which constantly attacks their caravans,” Marianne wrote. “They experience, however, the greatest consolation in the idea of meeting death as true Mahomedans should, with their faces towards Mecca.”

Kutch also played host to Muslims pilgrims from Central Asia. “The most interesting pilgrims I have seen in Cutch were a party of Uzbek Tartars from Yarcund, one of the western frontier possessions of China,” she wrote.

Beauty of the Rann

What impressed the Englishwoman the most was the Rann of Kutch: “Throughout Western India, nothing could, perhaps be found more worthy the observation of the traveler, than the great Northern Runn; a desert salt plain, which bounds Cutch on the north and east, and extends from the western confines of Guzzerat to the eastern branch of the River Indus; approaching Bhooj at its nearest point at about the distance of sixteen miles.”

She explained that the Rann was passable in the dry season but the glare from the incrustation of salt caused by the evaporation of water was so great that few people attempted to cross it unless they were motivated by business gains or military duty.

The beauty of the Rann awed her: “The distant aspect of the Runn resembles that of the ocean at ebb tide; and as some water always remains on it, the refraction of light produces the most beautiful and mysterious effects, decorating it with all the enchantments of the most lovely specimens of mirage, whose magic power, exerting itself on the morning mists, induces this desert tract with the most bewitching scenes…”

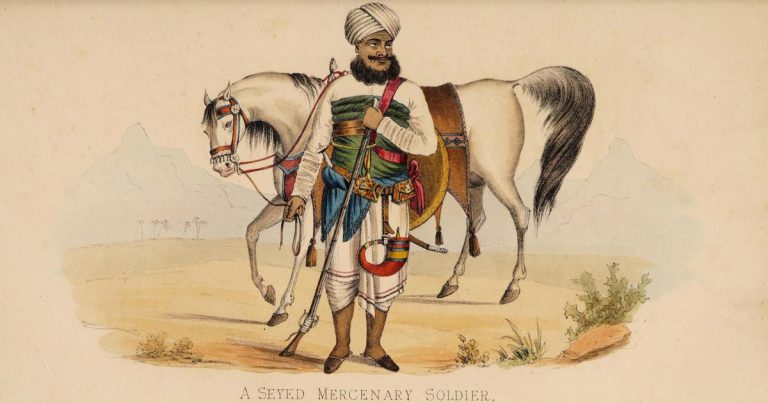

The book is by no means a romanticized look at Kutch. The writer describes in detail the social ills of the region, such as infanticide and the practice of sati. She is also very critical of the religious beliefs and customs of Hindus and Muslims. However, there is an attempt in the book to comprehensively describe the culture of the region, its bards and bardic literature, arts and crafts, and agriculture and trade – no mean feat for a woman in her 20s in that age. Making the book more interesting are her sketches that beautifully depict the region.

The book was published in London in 1839 and met with a great deal of success. Encouraged by the reception, Marianne next wrote a two-volume book titled Western India, which also covered Surat, Saurashtra, Bombay and the Deccan. She and her husband mostly lived in India, until he died in 1846. Marianne’s writing career continued for another couple of decades and included non-fiction about Sindh, Egypt, Switzerland and Gallipoli, where she travelled with her second husband during the Crimean War. She passed away at the age of 86 in Somerset in 1897. Looking back, her writings and sketches were pathbreaking for women and provide rare glimpses of 19th-century India in the English language.

_________________

Ajay Kamalakaran is a writer, primarily based in Mumbai. He is a Kalpalata Fellow for History & Heritage Writings for 2022.

Courtesy: Scroll (Published on Nov 24, 2022)