The craft was practiced by the Khatri community, living in the banks of river Sindh. These families migrated to Kutch from Sindh in the 16th century. Another account of history says that invasions led the Khatris to migrate en masse from Sindh to Katchch. There are both Hindus and Muslims among the Khatris.

The craft was practiced by the Khatri community, living in the banks of river Sindh. These families migrated to Kutch from Sindh in the 16th century. Another account of history says that invasions led the Khatris to migrate en masse from Sindh to Katchch. There are both Hindus and Muslims among the Khatris.

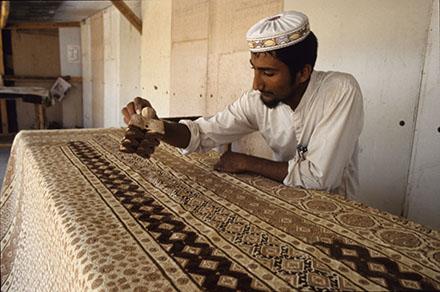

As you walk down the dusty path towards the village of Ajrakhpur in Katchch, about 8 km from Bhuj off the main Bhuj Bhachau highway, you begin to hear the sound of the craft that this village is famous for, indeed the name itself was derived from the name of its craft – ‘place of Ajrakh’ (Ajrak). You hear the whacking of meters and meters of wet cloth against the sides of the huge stone water tanks, and as you get closer to the workshops you hear the constant ‘thump – thump’ sound of the wooden block being stamped with force onto the table echoing through the workshop, the beating heart of the village. Then you see long pieces of dyed cloth in indigo, madder red, yellow, drying out in the sun stretching across the dry grass land into the distance. These are the sounds and sights that show the craft is still going strong. Despite environmental disasters, the widespread industrialization of the twentieth century and the changing political regimes, the traditional craft of Ajrakh, its long and skilled process and complex geometric designs have survived.

Key figure in preservation of Ajrakh

Key figure in preservation of Ajrakh

A key figure in this preservation of Ajrakh is the late Khatri Mohammed Siddique, who realized the new emerging markets for hand-crafted textiles in the 1970s. He revitalized the traditional use of natural dyes when realizing their appeal among Western markets, and passed the knowledge onto his three sons Ismail, Razzaq and Jabba. Mohammed Siddique was supported by the Gujarat Handicrafts Development Cooperation, a strand of the government’s initiative to revive India’s handicrafts after independence. Subsequently, various NGOs, textile companies and individual designers have supported the revival and continuation of the region’s traditional crafts.

More recently, a new approach has been taken to enable and encourage local artisans to work directly with their markets and become entrepreneurs and designers in their own right. Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya (KRV) opened in 2005 and since has had 136 graduates. Out of these, fifteen have been block printing artisans, and most are successfully innovating for a ready urban and international market. A new school has recently been founded by KRV founder Judy Frater, Somaiya Kala Vidya (SKV) based in Adipur southern Katchch. SKV aims to continue to focus on design education but also incorporate a strong business and marketing curriculum.

More recently, a new approach has been taken to enable and encourage local artisans to work directly with their markets and become entrepreneurs and designers in their own right. Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya (KRV) opened in 2005 and since has had 136 graduates. Out of these, fifteen have been block printing artisans, and most are successfully innovating for a ready urban and international market. A new school has recently been founded by KRV founder Judy Frater, Somaiya Kala Vidya (SKV) based in Adipur southern Katchch. SKV aims to continue to focus on design education but also incorporate a strong business and marketing curriculum.

The Khatris in Ajrakhpur and Dhamadka learn block printing from their fathers at the age of between ten and fifteen when they finish school. Often they are also natural entrepreneurs. With the marketing and contemporary design skills added, their opportunities are vast. These villages today are buzzing with new ideas and creativity.

The Khatris in Ajrakhpur and Dhamadka learn block printing from their fathers at the age of between ten and fifteen when they finish school. Often they are also natural entrepreneurs. With the marketing and contemporary design skills added, their opportunities are vast. These villages today are buzzing with new ideas and creativity.

Ismail Mohammed Siddique was a key figure in the relief efforts after the devastating earthquake of 2001 that destroyed much of the village of Dhamadka which has been a center for Ajrakh printing for centuries. He helped to build Ajrakhpur as a new place to rehabilitate the communities and the craft. Ismail’s family’s success has grown and grown over the years and they are continually having to seek out new land to build larger workshop and dying space. Ismail also helped to teach others the craft, and his success has spread to many other Khatri families too.

Ismail Khatri bestowed with honorary Doctorate

Ismail Khatri bestowed with honorary Doctorate

A PhD scholar called Eiluned Edwards visited Ismail Khatri in the context of studying textiles in India. Khatri, who was educated only up to Standard 7, agreed to meet her, hoping to try and speak in English with her. He responded to the questions she asked. The lady in question cleared her PhD, and in 2003 Khatri was invited by the De Montfort University in Leicester to talk on the art of Ajrakh. After his talk the University bestowed him with an Honorary Doctorate. Bewildered by why people were applauding him, he asked the person next to him, who turned out to be the Pro-Vice Chancellor of the University. He was told that he had been accorded the University’s highest degree. To which he said: “But I haven’t studied in your University!” He was then told that he had taught the students of the University much more. And that’s how Ismail Khatri became Dr. Ismail Khatri!

Watch the video about Dr. Ismail Khatri

One of Ismail’s sons, and three of his nephews (living in Dhamadka), have graduated from KRV and are contributing to the family’s success with new innovations. Khatri Junaid Ismail sold his whole KRV collection during the graduate exhibition. He experimented with different combinations of blocks and placement of color. He added new colors to traditional designs. His final collection was based on the theme of kudrat – life and creation.

One of Ismail’s sons, and three of his nephews (living in Dhamadka), have graduated from KRV and are contributing to the family’s success with new innovations. Khatri Junaid Ismail sold his whole KRV collection during the graduate exhibition. He experimented with different combinations of blocks and placement of color. He added new colors to traditional designs. His final collection was based on the theme of kudrat – life and creation.

Junaid and his brother Sufiyan continue to innovate within their tradition, creating diverse compositions, new combinations of techniques, materials and color combinations.

Khatri Khalid Amin returned to work as a block printer with his uncle after trying out sales work in Mumbai and disliking it. He attended KRV at the advice of Ismail, and his final collection included some expressive abstract pieces that combined the tight geometric Ajrakh prints with lively brush strokes and different textures. He has become well known throughout the urban and visiting foreign textiles and art community. His dupattas and stoles travelled to Manchester, UK for an exhibition at the Platt Hall costume gallery, and some were also featured in the 2011 edition of Wallpaper magazine.

Khatri Khalid Amin returned to work as a block printer with his uncle after trying out sales work in Mumbai and disliking it. He attended KRV at the advice of Ismail, and his final collection included some expressive abstract pieces that combined the tight geometric Ajrakh prints with lively brush strokes and different textures. He has become well known throughout the urban and visiting foreign textiles and art community. His dupattas and stoles travelled to Manchester, UK for an exhibition at the Platt Hall costume gallery, and some were also featured in the 2011 edition of Wallpaper magazine.

Khatri Irfan Anwar won an award for ‘most marketable’ collection at KRV. He is now an advisor on the new SKV course. His current innovations include large scale geometric designs with the dense detailed traditional Ajrakh embedded within. Thus, the traditional designs are still being used but in a very different way.

Khatri Irfan Anwar won an award for ‘most marketable’ collection at KRV. He is now an advisor on the new SKV course. His current innovations include large scale geometric designs with the dense detailed traditional Ajrakh embedded within. Thus, the traditional designs are still being used but in a very different way.

A current trend among the dyed and printed textiles in Kutch is combining Japanese shibori or local bandhani (tie-dye) techniques with block printing which produces a rich textural effect. It therefore showcases local and imported traditional techniques in a contemporary, innovative way. Each bandhani and block printing artisan employing these techniques has their own approach, so each piece is different and fresh.

In the face of climate change and globalization, there is a rising trend for all things hand-made, eco-friendly and an awareness of a product’s origin and culture. Such trends and awareness are sustaining the Khatris’ livelihoods and helping to preserve their long standing heritage. Let’s hope these are not just fleeting fashions and that the Khatris will continue to provide the world with a fascination for highly skilled, hand-crafted textiles for many generations to come.

In the face of climate change and globalization, there is a rising trend for all things hand-made, eco-friendly and an awareness of a product’s origin and culture. Such trends and awareness are sustaining the Khatris’ livelihoods and helping to preserve their long standing heritage. Let’s hope these are not just fleeting fashions and that the Khatris will continue to provide the world with a fascination for highly skilled, hand-crafted textiles for many generations to come.

The creation of Ajrakhpur

In the late eighties, the river Saran dried up because of the construction of a dam upstream. This affected the craft where copious quantities of running water were an essential requirement. The second disaster struck in 2001 when the earthquake at Bhuj left many families devastated. A new problem arose. The iron content in water increased after the earthquake which affected the color of dyes. A number of craftsmen shifted to chemical dyes instead of natural dyes. As expected, use of chemical dyes led to skin and other health problems. Seeing the impact of these practices on the art of Ajrakh, the community started looking for a new place around 40 km from Dhamadka, which had better water sources.

With the help and support of voluntary organizations, led by Ismail Khatri, almost 80 families of artisans bought land and shifted to this new village which was then named Ajrakhpur. The proximity to Bhuj ensured better facilities such as healthcare, education for their children, and business. Today almost every family in this craft village is engaged in Ajrakh printing, and you can see dyed cloth drying outside their houses.

With the help and support of voluntary organizations, led by Ismail Khatri, almost 80 families of artisans bought land and shifted to this new village which was then named Ajrakhpur. The proximity to Bhuj ensured better facilities such as healthcare, education for their children, and business. Today almost every family in this craft village is engaged in Ajrakh printing, and you can see dyed cloth drying outside their houses.

History of Ajrakh

Ajrakh is an ancient block-printing method on textiles that originated in the present day province of Sindh in Pakistan. The creation of vibrant, colorfast, cotton printing may date back as far as four millennia. There is a tantalizing similarity between the trefoil garment pattern found on a figurine recovered at Mohenjo Daro and a cloud pattern still used by block print artists working in Sindh and western India today. The shawl on the shoulder of this familiar bearded man bust from Mohenjo Daro perhaps has an Ajrakh motif called kakkar (cloud pattern), familiar to Ajrakh artists.

Archaeological evidence suggests that for thousands of years Ajrakh artisans were located near the banks of the Indus River. The river provided both a site for washing cloth and the water needed to grow indigo. With the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, artisan communities were tragically separated. Today the craft continues with variations on both sides of the border. Indian artisans are centered in Gujarat with most communities living in the Kachchh desert.

Archaeological evidence suggests that for thousands of years Ajrakh artisans were located near the banks of the Indus River. The river provided both a site for washing cloth and the water needed to grow indigo. With the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, artisan communities were tragically separated. Today the craft continues with variations on both sides of the border. Indian artisans are centered in Gujarat with most communities living in the Kachchh desert.

Ajrakh carries many meanings. A popular story among locals is that Ajrakh means “aaj rakh” or “keep it today.” It is also associated with azrakh, the Arabic word for indigo, a blue plant which thrived in the arid ecology of Kachchh. The craft was practiced by the Khatri community, living in the banks of river Sindh. These families migrated to Katchch from Sindh in the 16th century. Another account of history says that invasions led the Khatris to migrate en masse from Sindh to Kutch (Anjar and Dhamadka villages). There are both Hindus and Muslims among the Khatris. The present clan of artisans was led by their forefather Jinda Jeeva to Dhamadka village in 1650, where Rao Bharmal-I, the Raja of Kutch patronized their craft. Making Ajrakh needed a constant supply of running water to remove the excess dye, and Dhamadka was chosen as it had the river Saran flowing by.

In 2001 a devastating earthquake severely damaged Bhuj, Dhamadka and other villages and towns all over the Kachchh region. In the wake of this tragedy, the Khatris were brought closer together and a new village was created to rebuild their lives and their craft production, aptly named Ajrakhpur (‘place of Ajrakh’).

In 2001 a devastating earthquake severely damaged Bhuj, Dhamadka and other villages and towns all over the Kachchh region. In the wake of this tragedy, the Khatris were brought closer together and a new village was created to rebuild their lives and their craft production, aptly named Ajrakhpur (‘place of Ajrakh’).

How is Ajrakh made?

Ajrakh can be printed on a variety of fabric including cotton, linen, wool and silk (tussar, crepe, georgette, chiffon) The process of Ajrakh printing involves 14-16 stages.

Ajrakh block printing follows a lengthy and demanding process. Printers prepare fabric for printing by tearing un-dyed fabric into 9 meter lengths. Authentic Ajrakh is printed on both sides by a method called resist printing. The printing is done by hand with hand carved wooden blocks. Several different blocks are used to give the characteristic repeated patterning. Artisans select a wooden block from their collection of blocks carved with traditional designs. The constant sound of the wooden block being stamped with force onto the table echoes in the workshop and sounds almost like a heart beating. It is the sound that the craft is still going strong.

The Khatris themselves never wore block printed fabric. They produced Ajrakh traditionally for the Maldharis or cattle herders like the Ahirs or Rabaaris in the desert regions of Katchch and Thar. The colors are bright and vivid, so that the herders do not lose their way in the white desert sands. These geometric prints were usually seen in the pagdis (turbans), cummerbands, chaddars, dupattas, lungis and shawls used by the Katchchi community.

Every caste wore distinctive designs and Ajrakh is part of their cultural legacy. It is said that cattle herders would leave their homes in the dark, before the sun rose and there was no electricity in those times. So they couldn’t distinguish between the front and the reverse side of the fabric. Double-sided printing ensured that they could wear it both ways.

What are the threats to the Ajrakh industry?

What are the threats to the Ajrakh industry?

Water shortage in Gujarat and Rajasthan, which are affected by drought hamper the dyeing and printing process. Each step of the block printing art is manual. It needs not only skill but also patience to perfect this art. There are between 14-16 different steps in dyeing and printing, and each piece takes 14-21 days to complete. The screen printing industry makes cheap copies of their unique designs for a fraction of the cost. This undermines the market for these handmade products. The other issue is that of exacting perfection expected of these craftsmen. Since this is a completely manual process, and natural dyes are used, there are bound to be slight variations in the shades of the dye when large quantities of fabric are dyed. When these are rejected by the buyers, it causes distress to these craftsmen.

Watch a video about Ajrakhpur and Khatri community

___________________

Watch the video about Ajrak Making

___________________

In the last few decades, the artisans of Ajrakhpur have successfully managed to transform the everyday dress of the local cattle herders into a fashion fabric. When it isn’t used as sarees, stoles, dupattas or kurtas, the patches make their way into colorful quilts. The key to the resurrection of local crafts and keeping it alive perhaps lies here: by adapting to the times.

_________________________