The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse.

Julien Levesque

[The study of Sindhi nationalism has remained over-determined by the question of the allegiance of Sindhis to the Pakistani state. The movement has not been examined for itself but only from the vantage point of its success or failure. As a result, it has mainly received attention when sudden outbursts of violence seemed to threaten the stability of the state. However, few have attempted to examine what connects disparate events of ethnic violence and opposition to the central state with a broader understanding of what being Sindhi entails. Rather than address questions of failure or success, this article shows that the construction of a nationalist “idea of Sindh” has been a continuous process throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It also illustrates how an aspirational middle-class played a central role in this process. The article focuses on how three generations of Muslim men, who shared similar trajectories yet have unique social characteristics and repertoires of contention, constructed, reinforced, and disseminated the Sindhi nationalist discourse. This process translated into institution-building in the cultural sphere and contributed to the political outlook of a large section of Sindhi politicians on the left of the spectrum.]

The Political Itinerary of Sindhi Nationalism’s Main Ideologue

In his inaugural speech to the December 1943 Annual Session of the All-India Muslim League that took place in Karachi, G.M. Sayed described Pakistan as the Indus valley restored to its former political unity:

I welcome you all to the land of Sindhu. By Sindhu I mean that part of the Asian continent which is situated on the borders of the river Indus and its tributaries. But as time went on the name began to connote a smaller and smaller area, until now it is assigned only to that part of the land which is watered by tail end of this great river. Today again fully aware of this fact, we are moving to weld together these different parts into one harmonious whole, and the new proposed name, Pakistan connotes the same old Sindhu land.

At the time, G.M. Sayed was one of Sindh’s main protagonists of the Muslim League, the party that campaigned to establish a Muslim state in India. A few months earlier, in March 1943, he had moved a resolution in the provincial assembly by which Sindh endorsed the Pakistan project and was the first province to do so. Convinced to act in the best interest of Sindh, G.M. Sayed then promoted the Pakistan project. However, he later turned against the state and is now remembered by many as a traitor who advocated a separate Sindh.

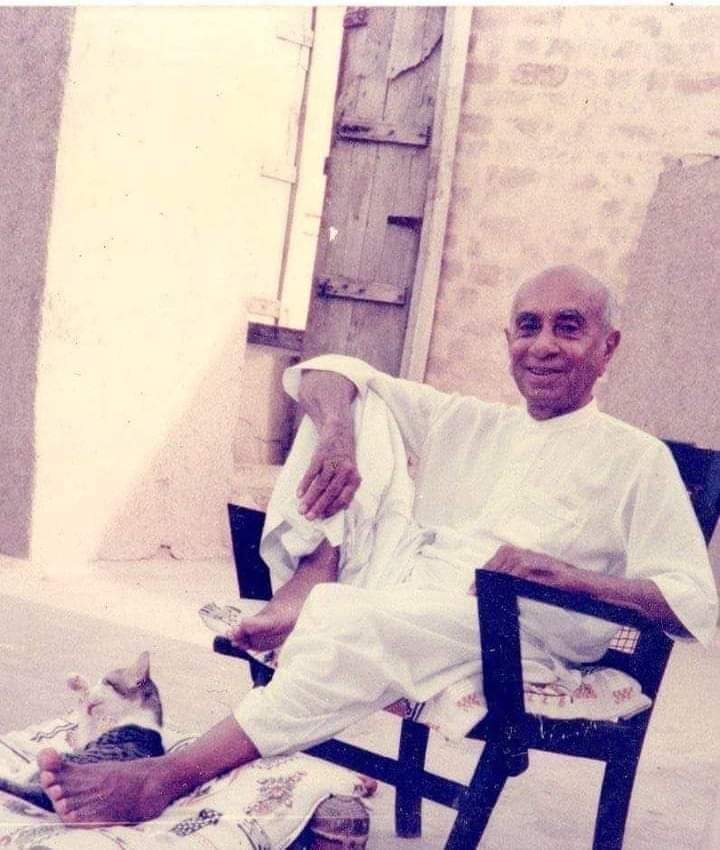

G.M. Sayed was born in 1904 in colonial Sindh. The British had annexed Sindh to their colonial possessions after defeating its rulers, the Talpurs, in 1843. For most of the colonial period, the British administered Sindh as part of the Bombay Presidency but made it a separate province in 1936. G.M. Sayed was born the heir of a spiritual lineage, a Sayyid – a person thought to descend from Prophet Muhammad – and a sajjada nashin – the hereditary custodian of a Sufi saint’s mausoleum. Thanks to these qualities, he was invited to participate in political meetings at an early age. In February 1920, Makhdum Moinuddin of Khiyari asked him to the first provincial session of the Khilafat movement, which fought against the abolition of the Caliphate following World War I. Being a sayyid and sajjada nashin bears particular significance in the religious context of Sindh. According to Kumar and Kothari, Sindh has “non-textualized religious practices” in which shrine worship plays a central role. Some authors attribute these characteristics to Sindh’s relative isolation from the main power centers – a “simplistically static picture” of Sindh as a margin that scholars are now beginning to re-evaluate. Endowed with a pedigree that made people look up to him for leadership, G.M. Sayed emerged in the late 1930s as a pro-Pakistan Muslim Leaguer. Although he had previously done a stint in the Congress Party, he now agitated on “communal” terms during the Masjid Manzilgah affair, a conflict between Hindus and Muslims over the use of a religious place.

However, G.M. Sayed soon fell out with the Muslim League and its central leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and the party eventually expelled him in 1946. While he had previously propounded the Pakistan project, he now began to fear negative fallouts of the birth of the new country for Sindh. Indeed, on August 14, 1947, Pakistan’s independence initiated tremendous demographic, social, and economic change as Sindh became the political and economic center of the new country. Karachi became the capital of Pakistan: the city not only hosted the new federal administration but also, along with other main urban centers of Sindh, offered shelter to hundreds of thousands of (mainly) Urdu-speaking refugees from India. By 1949, more than 700,000 immigrants had settled in Sindh, which significantly affected the language balance when combined with the departure of many Sindhi Hindus and Sikhs in 1948. The number of native Sindhi speakers fell from 87 percent in 1941 to 67 percent in 1951 and 55.7 percent in 1981. This fact was particularly the case in Karachi, as the city swelled in the years after partition. From about 435,000 inhabitants in 1941, its population rose to 1,126,000 in ten years. The city is now often thought to host more than twenty million inhabitants (although the last census in 2017 counted a little under 15 million people). Various subsequent waves of migration into Sindh kept fueling population growth.

These changes fed G.M. Sayed’s disaffection with Pakistan. The state’s repressive moves to thwart his political initiatives did not help: between 1958 and 1966, G.M. Sayed was under house arrest. This period was also when, during Ayub Khan’s military dictatorship, Sindh was merged with West Pakistan under the One Unit scheme. After Pakistan’s independence, G.M. Sayed gradually elaborated his thought and developed a framework to think about Sindh in nationalist terms that viewed the region as a cultural and historical entity that deserved to exist as a political unit. His numerous writings over four decades brought variegated tropes into a coherent nationalist discourse. He dwelled, for instance, on Shah Abdul Latif, an eighteenth-century Sufi, as a “national poet” of Sindh, Sindh’s particular spirituality beyond religious practice, the continuity of Sindhi culture through history, or the heroes of Sindh’s past.

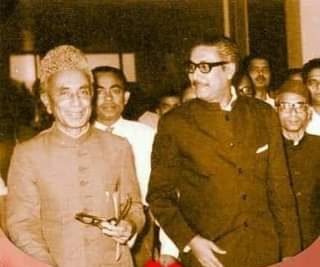

But the main turn in G.M. Sayed’s political career happened in late 1973 when he declared himself in favor of Sindh’s independence. Two years after the formation of Bangladesh, G.M. Sayed, who had expressed support for the demands of the Bengali leader Mujibur Rahman before the latter turned separatist, radicalized his political rhetoric and embraced the cause of an independent Sindh – “Sindhudesh.” Several causes may explain this radicalization: the independence of Bangladesh, G.M. Sayed’s total distrust of the Pakistan army and central authorities following the bloody military operation against Bengali and Baloch separatists, and his disappointment with Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who showed himself ready to compromise with the army in his quest for power. In his writings, G.M. Sayed described the adoption of a separatist stance as the last option. Indeed, a reluctance might be inferred from the absence of any sudden grand or bellicose declaration of separatism. Instead, his new political outlook seems to have taken shape progressively throughout multiple public speeches in 1972 and 1973. His later books clearly argued for Sindh to become free and for the break-up of Pakistan. His political party, the Jiye Sindh Mahaz, and its student wing became public advocates of Sindh’s independence. In the political arena at this time, G.M. Sayed grew more isolated. His 1970 campaign had been an utter failure. He was placed under house arrest by Z.A. Bhutto’s government in August 1972 because it viewed him as fueling ethnic tensions in the wake of the provincial government’s attempt to restore the official status of Sindhi.

Nonetheless, G.M. Sayed’s political stance, if obstinate, often seemed ambiguous to observers. Justified in terms of the pursuit of “Sindhis’ rights,” his support for the separatist cause appeared at times blind to the actual suffering of Sindhis. G.M. Sayed, driven by his opposition to Z.A. Bhutto, his family, and his political legacy, refused to support the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) in 1983, a multi-party coalition led by late Bhutto’s daughter Benazir and her Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). The military violently crushed the massive uprising in Sindh, but G.M. Sayed did not budge. Although he argued that the MRD stood for the preservation of Pakistan while he sought to break it, many saw this move as personal rivalry trumping political concerns. It eroded his credibility by making him appear as an apologist of Zia ul-Haq’s military dictatorship. On the other hand, the two crucial actors of the MRD in Sindh – the PPP and the Awami Tehreek – gained immense popularity as the parties who fought against the army’s might.

At the same time, G.M. Sayed’s support for the separatist cause also sometimes seemed to falter. In 1984, his failed attempt to bring a non-separatist at the helm of the JSM only served to accentuate the discrepancy between the leadership and the activists, who vehemently reiterated the Sindhudesh cause. G.M. Sayed seemed ready to forego the pursuit of independence when he could make electoral gains. When democracy returned to the country in 1988, he attempted to bring several parties into an electoral alliance, the Sindh National Alliance (Sindh Qaumi Ittehad). However, after initial negotiations, the other leading player, Rasul Bakhsh Palijo, and his Awami Tehreek messed up the project by refusing to allow space for Sindh’s Urdu-speaking population, represented by the Mohajir Qaumi Movement. To him, the proposed alliance had to be named “Sindhi National Alliance” (Sindhi Qaumi Ittehad) – a coalition of and for ethnic Sindhis – rather than “Sindh National Alliance” – including all populations of Sindh. Meanwhile, in a period of acute ethnic tension that soon led to repeated violent conflict in 1988–1990, G.M. Sayed met with the MQM leader Altaf Hussain. The SNA fell apart, and its members or associates fared poorly in the 1988 elections, both in the national and provincial assemblies. Yet, the SNA allowed for nationalist parties (whether autonomist or separatist) to emerge as a pressure group that forced the elected PPP representatives to step back on specific issues. It was the case with a plan to repatriate “Biharis” from Bangladesh: Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto abandoned the project in 1989 when the SNA and the JSM protested it.

In April 1995, G.M. Sayed died, leaving a fragmented and controversial heritage. But many of the issues that had nourished Sindhi resentment in the 1950s were still matters of conflict. It was true for the place of the Sindhi language and culture, the use, management, and distribution of resources (mineral, hydrocarbons, water, land), and the question of immigration into Sindh. According to the 2017 census, Sindh now has about 48 million people, or 23 percent of Pakistan’s total population, for about 16 percent of the country’s territory. Although the federal capital of Pakistan moved to Islamabad in the late 1960s, Karachi remained the main harbor and the economic hub of the country, contributing the largest revenue share to the federal exchequer. In addition, the development of irrigated agriculture over the twentieth century and the discovery of natural resources (oil, gas, and coal) reinforced the economic importance and strategic position of Sindh. (Continues)

__________________

Julien Levesque holds a Ph.D. (2016) in Political Science from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris. His doctoral research focused on nationalism and identity construction in Sindh after Pakistan’s independence.

Courtesy: Brill

( Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Originally published by Journal of Sindhi Studies – Edited by: Matthew A. Cook (USA) and Michel Boivin (Paris). The primary focus of the Journal of Sindhi Studies (JOSS) is the Sindh region, located in southern Pakistan. However, Sindhis live in other parts of Pakistan as well as in India and across the globe. The journal accepts submissions that address the people of Sindh, regardless of their current geographic location. JOSS aims to shed interdisciplinary light on the “Sindhi World.”)

Click here for Part-I