Today, these towns lie deserted — an eloquent comment on the ecological devastation that has visited the Indus delta. What went wrong?

Arif Hasan

STARVED of fresh water and no longer able to withstand the encroaching Arabian Sea, the Indus is dying a slow death. The channels of this mighty and historic river are running dry, while salt water is destroying the lush tamarisk forests which once lined the river, the estuarine timmar, or mangrove swamps, and the red rice paddies.

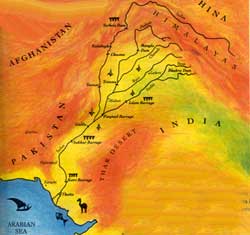

The destruction of the Indus delta is a direct consequence of the dams and barrages that have been built higher up on the river. These have diverted the river’s water into areas that were earlier rain-fed, drastically reducing the quantity of water flowing into the deltaic channels leading and, thereby, increasing salinity.

Keti Bunder, which lies to the east of Karachi, was once a bustling port and trading center with a population of 40,000. Today, it’s a ghost town. Most of its residents have long since migrated to more economically viable areas. Its active rice mills now lie neglected and its water supply systems no longer function because of lack of drinking water.

Shah Bunder tells a similar story, as do several other port towns which once dotted the coast. It was from here that Arab dhows, laden with timber, charcoal, rice, ghee, and camels, set sail for Dwarka, Gumti, Muscat, Aden and other ports in the Persian Gulf. The Memon and Shidi merchants and Hindu bankers of these towns were an affluent and cosmopolitan people with strong links with communities living across the seas. Keti Bunder once had a municipal committee, street lighting and a large rice husking mill in an era when mechanically operated mills were rare.

Shah Bunder tells a similar story, as do several other port towns which once dotted the coast. It was from here that Arab dhows, laden with timber, charcoal, rice, ghee, and camels, set sail for Dwarka, Gumti, Muscat, Aden and other ports in the Persian Gulf. The Memon and Shidi merchants and Hindu bankers of these towns were an affluent and cosmopolitan people with strong links with communities living across the seas. Keti Bunder once had a municipal committee, street lighting and a large rice husking mill in an era when mechanically operated mills were rare.

Before the Punjab canal colonies were developed at the turn of the century and the barrages came up (between 1932 and 1960) to meet local irrigation needs, the Indus discharged over 5,660 cusecs of water on an average into the Arabian Sea, through over a dozen distributaries and creeks, whose names are part of the political and navigational history of the Indian, Arabian and African coastline and of the folklore of lower Sindh. The marine currents that developed due to this discharge affected navigation for over 500 km off the coast, and the muddy waters of the Indus decolorized the blue-grey Arabian Sea for over 60 km from the shore.

This intense tussle between the sea and the river forced the waters of the Indus to spread into numerous channels at its mouth, thus creating the Indus delta region, which covered an area of over 3,000 square km. Since a major part of the 1 million tons of silt that the Indus waters carry with them daily settled on this land, it became the most fertile area in the river valley.

The delta region consisted of three distinct areas. In the upper reaches, there was thick lai, or tamarisk forests, sustained by the annual flooding of the river. Below them were the mud flats which were covered with sohand and pal grass and large quantities of the lana shrub. And, finally, where the sea and the delta channels met, were the timmar, or mangrove swamps, where almost all the marine life in the coastal region is conceived. All three forms of vegetation bound the soil together and made it possible for the delta to not only absorb the silt that the river brought with it, but also to push the delta region into the sea by about 3 sq km every year. There is evidence to indicate that the delta has moved some 100 km into the sea since Alexander’s time, when Thatta was a port.

The nature of vegetation in the different parts of the delta region determined the nature of the productive activity that was carried out in them. The Jats, who inhabited the tamarisk forests, cut them for timber in a big way. A large part of this timber was converted into charcoal by burning. This activity took place in autumn and winter when the river had receded. Before coal replaced timber as fuel for the railways, 283,000 cubic meters of timber per year was used in Sindh for the Northwestern Railways. Most of it came from the delta region.

The sohand and pal grass in the mud flats made excellent fodder for buffaloes and cows, and the region produced a considerable amount of ghee and butter. The main agricultural crop was red rice, which was cultivated almost without ploughing as the river deposited large quantities of silt on the seeds that the farmers scattered on the mud flats between the delta channels. The yields here were higher than anywhere else in the Indus valley. The lana shrub and the mangrove are both eaten by camels, so the area adjoining the mangrove marshes were used for breeding the finest camels in Sindh. And, finally, in the saline creeks of the region, the Dabla clans carried on subsistence fishing activity.

Although the waters of the Indus and its tributaries were diverted to the floodplains of the Punjab even during the reign of Sher Shah Suri and Akbar, there is little evidence that this decreased the flow of the river to any extent. At the turn of the century, the colonial rulers siphoned away water for perennial irrigation in the Punjab doabs — the areas between the major rivers of Punjab. Between 1872 and 1929, the British rulers built weirs across all the eastern tributaries of the Indus to divert the river water into canals. Weirs were also constructed on the Kabul and Swat rivers and on three sites on the Indus itself and its inundation channels. Most of the upper Indus plain, thus, received perennial water and the desert was brought under the plough.

This resulted in the westernmost seasonal channels on the delta ceasing to function. Since the extent of inundation also decreased, some tamarisk forests were affected. But because the volume of the water diverted was still only a small percentage of the total Indus water, the ecological effect of all these changes was not serious.

However, the social, cultural and economic complexion of the Punjab underwent a complete transformation. As a result of a massive government program, people from the more progressive and densely populated areas of eastern Punjab were encouraged to settle in the new canal colonies, displacing the local agriculturalists of the Indus floodplain. There was obvious resistance to these changes. In fact, in the Jang area on the Chenab, the locals (Janglis), were labelled criminal tribes by the British and completely marginalized, while the more aggressive eastern Punjabis colonized their lands.

Traditionally, the people of the barani (rain-fed) regions would descend to the sailaba (flooded) areas with their livestock, after harvesting their kharif (summer) crop, to work as artisans and in the rabi (winter) fields of the settled agriculturalists. They were given permission to graze their animals and, after the harvest, collect crop residues for their livestock. With perennial irrigation, this community, too, was marginalized.

A new dynamic, educated Punjabi entrepreneurial class emerged from the eastern Punjab towns of Ludhiana, Amritsar and Lahore. Even today, the manjha-speaking Punjabis dominate the landa-speaking people of the region. They bought lands and undertook canal construction contracts. Building the canal colonies involved major engineering work, and over 500,000 people participated in their construction in the last two decades of the 19th century alone. A large irrigation department was created to extend, operate and maintain the canals and headworks, while traditional institutions were bypassed in the process. The real environmental crisis became apparent when the Sukkur barrage was commissioned in 1932. Fresh water disappeared for four months of the year from all the Indus channels, except the Haidari and Oshta branches. During these months, the sea would creep into the mud flats and the mangroves were no longer flushed with fresh water. The government at the time wanted to relocate the Dabla fisherfolk, but they were reluctant to move and were eventually forgotten.

When the Ghulam Mohammad Barrage at Kotri became operative in 1958, the fate of the delta was sealed. Fresh water flow ceased in the channels, except for a few weeks in the flooding season. The sea flooded the lower distributaries for good and the fertile mud flats were rendered saline and unfit for cultivation. Between 1932 and 1962, four major barrages were built on the Indus at Sukkur, Kotri, Taunsa and Guddu.

After the Indo-Pak Indus Treaty was signed, two major dams at Tarbela and Chasma were constructed on the Indus and the Mangla on the Jhelum, a tributary of the Indus. Over 74 per cent of the waters of the Indus system were thus removed before the Indus reached Kotri, and the delta region shrunk to 250 sq. km.

The rice mills slowly ceased to function and increasing salinity destroyed the tamarisk forests in the upper delta region. These were auctioned out to contractors and cut down. The pasture lands are now barren and the silt that used to stabilize the coast has disappeared, endangering the coastal mangrove ecosystem which was a nursery for a number of marine species. With the decreasing quantity of silt, nutrients essential for developing marine life have also got depleted. The dams and barrages have prevented the much favored migratory fish, palla, from swimming upstream to spawn. An area which used to produce a surplus of dairy products till the late 1950s, it now depends on imported milk powder to meet local needs.

Drinking water became scarce in all but the Haideri mouth of the river. Since the survival of both people and livestock became impossible in these conditions, agriculturists and pastoralists, who could afford to do so, moved out to the newly-colonized barrage areas in Jati, Sujawal, Thatta and Badin. The Arab dhows unfolded their sails and sailed away forever. Subsistence agriculture became extremely difficult and only the Dabla fisherfolk and Jat camel-breeders stayed on to force a living out of the saline water and timmar swamps. Water is now obtained in small boats from the Haideri channel or piped from perennial canals constructed recently in some areas. The impact these ecological changes had on the social life of the communities living along the length of the Indus was considerable. The Mohana fishing community gave up their traditional fishing grounds and moved to barrage areas which became new fishing areas. But here they had to take high interest loans from traders to purchase boats and nets. Simultaneously, the ancient Mirbahar community of the central Indus plains was decimated. They could no longer operate their cargo crafts along the Indus as these could not pass through the barrages. River transport declined rapidly and was replaced by road transport.

But this story of ecological and social change does not end here. In the upper region of the delta, perennial canal irrigation from the Ghulam Mohammad Barrage was developed. Whatever little was left of the tamarisk forest was cut and burnt to extend agriculture. Effective drainage through gravity flow could not be developed as the delta region was much too flat, and power and resources for pumping were unavailable. Waterlogging and salinity set in, making it impossible to cultivate traditional food crops. The ancient mango and guava orchards perished and were replaced by salinity-tolerant coconut palms, sugarcane, bananas and tomatoes. Since the cultivation of these cash crops required substantial financial inputs, the poor were marginalized even further.

Plans to deal with salinization and waterlogging have been floated, but they are likely to do more harm than good. The government has initiated the Left Bank Outfall Drain project to overcome the drainage problems of the lower Indus plain, with assistance from the World Bank, the Overseas Development Agency of the British government and the United Nations Development Program. This project aims at draining water through a main spinal channel to the Rann of Kutch and the Arabian Sea. However, the maintenance and operation of this massive system will pose enormous financial, managerial and technical problems.

In the lower delta region, too, new economic developments have taken place. The fisheries industry has grown substantially. The fisheries department was set up by the government in the 1960s and loans for boats and nylon nets were floated. This move coincided with the development of large-scale poultry farming in the Karachi area and led to the establishment of chicken-feed factories which turn enormous quantities of fish into chicken-feed.

From the 1960s, there has been a growing demand for Pakistani prawns, lobster and fish in the international market. This, in turn, has encouraged the Memon and Shidi middlemen and bayparis from Karachi to advance loans to the local Dabla fisherfolk. Large mechanized boats have replaced the traditional sail boats. New nets and fishing techniques have been introduced and more people have gravitated to the fishing industry.

While this has created seasonal job opportunities for the fishing community in Karachi and raised the awareness level of people engaged in this trade, it has also helped to create an iniquitous social order. Environmentally, too, many feel that fish stocks are being depleted by the Karachi trawlers.

Although the fishing industry has now developed into the sixth largest foreign exchange earner in Pakistan, the economic lot of the Dablas has not improved. The same is the case with the Jats and Khashkhelis. These communities have now been forced to take up fishing which they once considered infra dig, because their earlier pastoral and agricultural occupations have become unviable.

The absence of good road links in the region reinforce the isolation of these people. Traditionally, the residents of Mianwali, a port city on the Indus just south of Peshawar, controlled river transport and fisheries. Today, they have monopolized the road transport business and established cold storage facilities and ice factories along the coast to service their activities. There are signs that overfishing by commercial vessels operated either by foreign companies or through joint ventures between local and foreign firms, is leading to a decrease in the catch. With the Indus dying a slow death, the mangrove swamps which support marine life along the coast, are also threatened.

The people of Keti Bunder and its surrounding settlements, having observed the degradation of their environment at first hand, understand the reasons for it. The lower delta region that the great river created is in its death throes. Although nothing can be done to reactivate the delta channels, the mangrove ecosystem can be protected and revived. This is the only hope for the marine life of this region. And for its human settlements.

_________________

Arif Hasan, is a Pakistani architect, planner, activist, social researcher, and writer.

Arif Hasan, is a Pakistani architect, planner, activist, social researcher, and writer.

Courtesy: Down To Earth