When Ebtehaj passed away in Germany on August 10, 2022, Iranian Embassy in Berlin mourned his demise with “all the lovers of Persian culture and literature in the entire world.”

Sindh Courier

One day, he and his cellmate heard the iconic Iranian song played on the prisoners’ loudspeakers – ‘Iran, Ey Saraye Omid’ (Iran, the place of hope). Tears broke out of his eyes as soon as he heard this song. His cellmate asked ‘why was he crying?’ He replied ‘Because I wrote the lyrics for this song.’ His cellmate, surprised by his reply, asked, ‘then why are you in prison if you had written this song?’

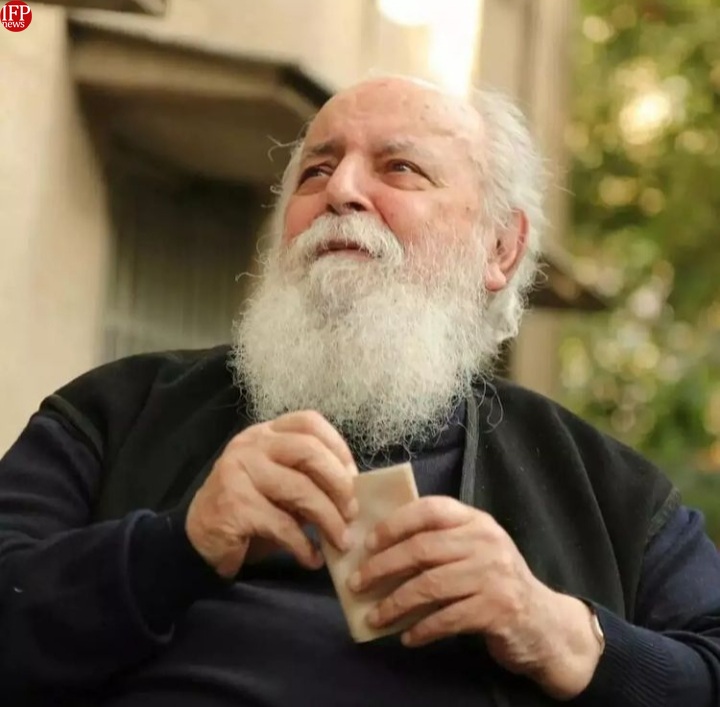

The prisoner, who cried on listening to the song, was none but outstanding Iranian poet Ebtehaj, who passed away in Germany on August 10, 2022 at the age of 94. The cause of death was kidney failure, according to Iran’s semiofficial media. Ebtehaj had lived in Germany since the late 1980s.

Ebtehaj, whose full name was Amir Houshang Ebtehaj امير ھوشنگ ابتھاج had shared his above mentioned prison memory in an interview. Ebtehaj literally means Sayeh or shade.

His daughter, Yalda Ebtehaj, had said on Instagram that her father, known by his pen name “Sayeh,” or Shadow, had “joined the other world.” In the post, she quoted a verse written by her father in the style of the great mystic poet Rumi: “Roam, roam, roam … There are strangers in this home, so you strangely roam.”

Ebtehaj was born on February 25, 1928 in Iran’s city of Rasht, some 240 kilometers northwest of Tehran in a Bahai family. He began writing when he was young and published his first book of poetry when he was just 19. Throughout the 20th century, Ebtehaj contributed to the popularity of the ghazal — a traditional form of Persian poetry set to music that expresses the writer’s feelings, especially about love, with moving intensity.

Ebtehaj was born on February 25, 1928 in Iran’s city of Rasht, some 240 kilometers northwest of Tehran in a Bahai family. He began writing when he was young and published his first book of poetry when he was just 19. Throughout the 20th century, Ebtehaj contributed to the popularity of the ghazal — a traditional form of Persian poetry set to music that expresses the writer’s feelings, especially about love, with moving intensity.

Though the variety of his poems isn’t astounding, his poetry is distinguished by an abundance of emotion and meticulously chosen phrases.

During Iran’s open period following World War II, Sayeh got involved in various literary circles and contributed to various literary magazines such as Sokhan, Kavian, Sadaf, Maslehat, and others. Unlike many other literary figures of the time who got deeply involved in politics and left-leaning activities, Sayeh stayed true to his social and political consciousness but refrained from deeper involvement. He was employed at the National Cement Company for 22 years while continuing his literary activities. Later he was invited by the National Iranian Radio to produce the traditional music program “Golhaye Taze” and “Golchin Hafte.”

Suffused with romance and melancholic longing, his body of work was not regarded as overly political. But socialist politics were central to Ebtehaj’s identity. He sympathized with Iran’s Communist Tudeh Party, and paid the price after the overthrow of Iran’s secular Western-backed monarchy in 1979. During the young Islamic Republic’s crackdown on leftists and liberals after the revolution, Ebtehaj landed in prison for nearly a year.

He was released in 1984, when a well-known Iranian poet appealed to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was then president, to secure Ebtehaj’s freedom. The poet, Mohammad-Hossein Shahriar, wrote in a letter that Ebtehaj’s detention caused angels to weep on God’s throne.

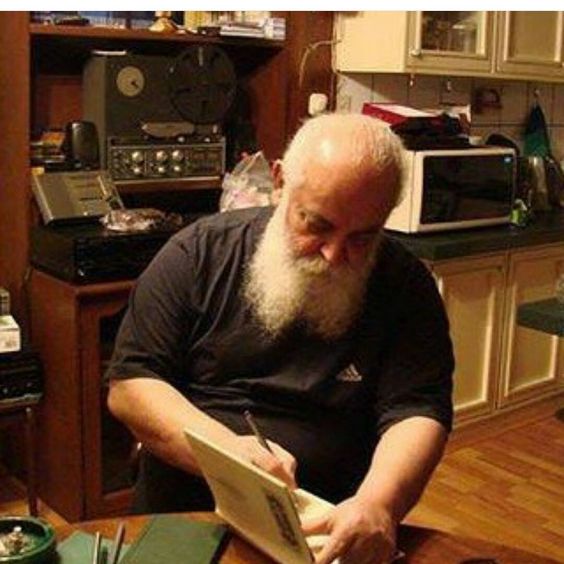

After he was released, he began to work on “Hafez, by Sayeh,” a verse-for-verse study of the various publications of Hafez. In 1987, he moved to Cologne, Germany, with his family and lived there, but he visited Iran several times a year.

After he was released, he began to work on “Hafez, by Sayeh,” a verse-for-verse study of the various publications of Hafez. In 1987, he moved to Cologne, Germany, with his family and lived there, but he visited Iran several times a year.

Across his 70-year career that traced Iran’s tumultuous history, Ebtehaj became recognized for his innovative verses that built on the foundations of Rumi and the celebrated 14th-century Persian poet Hafez, combining traditional forms with modern social themes.

He was also a musicologist and scholar, lecturing at universities across Europe about the mystical lyrical poetry of Hafez. However, the international reach of his poetry remained limited, with only one collection translated into English.

In the political climate of the 1940s, Sayeh was an ardent advocate of the poetry of social commitment. His own early poetry reveals his concern with purposive literature.

Sayeh has also written a collection of lyrical poems (ghazal) in the classical style. Here, he reveals an easy mastery of traditional forms—the lyrical ode, in particular—which he uses to celebrate both the sacred and the secular moments of life. Sayeh’s poetry, at times highly emotional, is always remarkable for its convincing directness and unconcealed sentiment. A number of his lyric poems, ballads and poems have been performed by famous Iranian singers such as Mohammad Reza Shajarian, Alireza Eftekhari, Shahram Nazeri, Hossein Ghavami and Mohammad Esfahani.

Works

The First Songs, 1946 (نخستین نغمهها); Mirage, 1951 (سراب); Bleak Travails I, 1953 (سیاه مشق ۱); Nocturnal, 1953 (شبگیر); Earth, 1955 (زمین); Pages from the Longest Night, 1965 (چند برگ از یلدا); Bleak Travails II, 1973 (سیاه مشق ۲); Until the Dawn of the Longest Night, 1981 (تا صبح شب یلدا); Memorial to the Blood of the Cypress, 1981 (یادگار خون سرو); Bleak Travails III, 1985 (سیاه مشق ۳); Bleak Travails IV, 1992 (سیاه مشق ۴); Mirror in Mirror, Selected Poems, 1995 (آینه در آینه); (Selected by M.R. Shafie-Kadkani); Dispirited, 2006 (تاسیان) (non-ghazal poems); Hafez, by Sayeh, 1994 (حافظ به سعی سایه).

Ebtehaj is survived by two sons and two daughters. His wife, Alma Maikial, died last year.

Condolences poured in from scores of Iranians on social media, as well as Iranian cultural institutions and embassies.

Iran’s Embassy in Berlin also mourned his demise with “all the lovers of Persian culture and literature in the entire world.”

Here is one of his poems, translated into English by M. Alexandrian

Liberty

O joy!

O liberty!

O joy of liberty!

When you return,

What shall I do

With this melancholy heart?

Our sorrow is heavy,

Our hearts are bleeding,

Blood spurts from our heads to our feet,

From head to foot we are wounded,

From head to foot we are bloody,

From head to foot we are all pain.

We have exposed our loving heart to hazards

For your sake.

When the tongue feared the lip,

When the pen doubted the paper,

Even, even our recollection dreaded to speak during dreams,

We used to engrave your name in our heart

Like an image on turquoise.

When in that dark street,

Night followed night,

And the horror of its silence

Crashed on the closed window,

We spread your voice like spurting blood

Like a stone thrown in the swamp

On the roof and at the door.

When the deceit of the beast,

Disguised in Solomon’s garment,

Wore the ring on his finger,

We used to rhyme your secret, like God’s mightiest name

In poetry and ode.

We spoke of

Wine, of flower, of morning,

Of mirror, of flight,

Of Phoenix, of the sun.

We spoke of light, of goodness,

Of wisdom, of love,

Of faith, of hope.

That bird that journeyed in the cloud,

That seed in the ground that grow into a lawn,

That light that danced in the mirror,

And murmured to our heart’s solitude,

Spoke of meeting you at every breath.

In the school, in the market,

In the mosque, in the town square,

In jail, in chains,

We murmured your name:

Liberty!,

Liberty!

Liberty!

Those nights, those nights, those nights,

Those dark and horrible nights,

Those nights of nightmare,

Those nights of tyranny,

Those nights of faith,

Those nights of shouting,

Those nights of patience and awakenings,

We sought you in the street,

We called your name on the roofs:

Liberty!,

Liberty!

Liberty!

I said:

“When you return

I will lift my young heart

Like the banner of victory,

And will hoist

The bloody banner

On your lofty roof.

I said:

“On the day that you return,

I will strew this blossoming blood,

Like a bouquet of rose,

At your foot;

And will hang

My rolling arms

Around your proud neck.

O liberty!

See!

Liberty!

This carpet lying under your foot,

Is dyed with blood.

This flower garlands is made of blood,

It is the flower of blood…

O liberty!

You come through the alley of blood,

But

You will come and I tremble in my heart:

What is this which is concealed in your hand?

What is this which is twisted around your leg?

O liberty!

Are you

Coming

With chains?

___________________

Source: New Idea Blog, Washington Post, Wikipedia, Caroun