Second World War, which started as a battle between man and machine, ended with the machine’s victory, in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nazarul Islam

What has happened to literature’s brave men, who had longed for, then went to Wars? America’s author Earnest Hemingway, arguably the most masculine of writers, ran repeatedly towards dangers throughout his life — along with, any other intense experience he could find. This being accomplished, he’d write about it: both fiction and nonfiction, covering topics of bravery and his men (the heroes).

The people in his stories were hit-men or those who had engaged themselves in sports like boxing, fishing, hunting, bullfighting, racing and extreme sports—and were revered and highlighted.

War, the subject of Hemingway’s two most famous books, is perhaps the quintessential subject of such manly writing.

Let’s recall…the contents of at least two epics, the Mahabharata and the Iliad. In both narratives, the central theme includes the ancient world’s most immortal works. However, something unusual has happened to the present day, war-literature—first, the industrialization of combat fighting, which Hemingway himself lived through and documented; then, the development of war technologies so terrible that battle itself came to seem the ‘unthinkable’.

Our world that has emerged since, is in many ways (or at least in many places) a safer and more peaceful one. But what has become of those men who actually liked or like danger, and for whom—warfare has always been a proving-ground. Perhaps yes?

Some of the diehards are still addicted to running into danger. Or, life threatening challenges! There was a surreal echo of Hemingway’s love of danger, in a recent wave of young Americans joining a conflict overseas, and then (albeit with less positive consequences) documenting it.

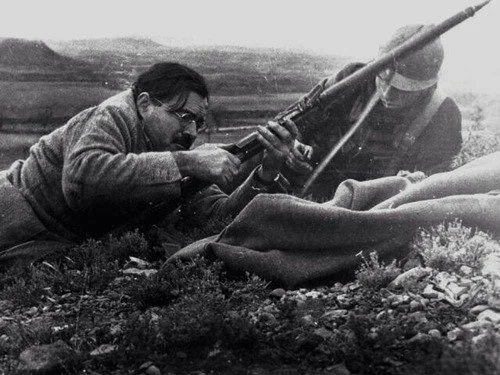

Hemingway was among the thousands who had travelled to Spain between 1936 and 1938, to support the Republican side against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Earlier, in February, the Ukrainian president Zelenskyy issued a formal call to foreigners to join an “international brigade” fighting for the Ukrainian side against Putin’s invasion.

At least according to Ukrainian reports, an estimated 20,000 have signed up to help — and many view what they’re doing as fight back against “a 21st-century version of fascism”.

One would think the Weird ‘Online Right’, the contemporary subculture most concerned with masculinity would approve of this risk-taking. A recurring theme in such spaces is the perceived subjection of manliness to the shrunken, heroism-free horizons of modern life and the culture of weirdos it has produced. Perhaps the most influential sacred text of this subculture is Bronze Age Mindset, an unclassifiable “exhortation” written in 2018 and now immensely influential among disaffected young men.

For a while Hemingway remained a byword for “masculine” writing. There is also a tragic sense in which his work traces the Twentieth-century demise of an older, more warlike form of masculinity, at the hands not of the “endless sallow night of matriarchy” but of technology itself.

For avid readers, War literature prior to the Twentieth century is often unabashedly heroic, even as it documents horrors. Tennyson’s 1855 Charge of the Light Brigade describes an 1854 battlefield in the Crimea in terms both terrible and stirring, then asks:

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

“When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality,” Hemingway wrote in 1942, of his experiences as an ambulance driver in World War I when he was just 19. “Then, when you are badly wounded the first time, you lose that illusion.” The war that deprived Hemingway of his illusions about immortality also stripped many of confidence in military glory full stop.

An English poet and soldier Wilfred Owen’s work Dulce et Decorum Est, published 1921, had drawn a contrast between the heroic motto about dying for one’s country, and the reality of dying of poison gas in the trenches. In 1935, Hemingway expressed the same sentiment in an Esquire essay, where he stated that “in modern war, there is nothing sweet nor fitting in your dying. You will die like a dog for no good reason”.

Even so, to Earnest Hemingway the Spanish Civil War was a clear-cut moral issue: a battle between good and evil, man and machine, via the horrifying industrial technologies of Twentieth-century total war. And if, as some historians argue, this conflict was in fact the true start of the Second World War, what started as a battle between man and machine ended with the machine’s victory, in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A whole generation, born in the fifties, like myself have grown up in the shadow of Mutually Assured Destruction: the fear that either (or both) sides in the Cold War might at any moment launch unstoppable nuclear-powered death through the air, obliterating millions in seconds.

Over the same period, conflict between nuclear powers avoided any, direct confrontation.

Armies have shrunk, nationalism has been widely deprecated, and the world (unless you’re unlucky enough to live in a theatre of one of America’s or Russia’s proxy wars, or the flashpoint in the Indian subcontinent) is generally more peaceful than in Hemingway’s youth.

And while that has many upsides, it has also, paradoxically, created disaffected young men. For when national identity is demeaning and open warfare is discouraged lest it set off nuclear Armageddon, what’s left for young men who wish to quench their thirst from the elixirs of danger and intensity?

Some find it anyway; some, too, also write about it. A journalist who had reported in the year 2014 of his experiences in Syria, had these words to comment: “The hidden awful truth about war is how much fun it is.” But for those in the developed West, this is the exception rather than the rule. Most men remain in the “Iron Prison”. Many chafe at it, and seek to reclaim some form of masculinity, but few seem very certain as to how this might be done in practice.

Some, too, write about impeding or hampering nature of the world in which they remain.

Today’s modern life has become an economic zone arranged much like a work camp, a regimented place “of incredible ugliness” and “hateful to the raising of boys”.

And with heroism, action or drama in short supply in everyday life, those hungry for intensity must resort to the world of computer gaming.

Hemingway began his life in the shadow of Tennyson’s Light Brigade, and finished it in the shadow of Hiroshima. Over the same period, the raw, elemental struggles between man and man, or man and nature, so characteristic of Hemingway’s work, grew down in intensity or force. His literary career was both as a “masculine” writer, but also as an elegy for a world where the conventionally masculine virtues of courage, risk-taking, stoicism and heroism were easily celebrated and widely accepted as culturally essential.

Since his time, the world has retreated steadily from conflict, toward mechanized and then mediated life; a process culminating in the radical safetyism and dematerialized common life of Covid lockdowns, and the online-first social life the pandemic ushered in. And now that we have virtualized social life to the point where any physical violence is foreclosed, even most arguments about masculinity now inevitably take place in the feminine key.

Young men, already restive, are growing mutinous, influenced by the unusual phenomena or life’s ongoing regime. The lurid and angry literature emerging captures these men’s ambivalence: sickened by, but also usually still implicated in, the banality and perceived ‘feminine’ traits of a modern world—that is denuded of both danger and opportunity.

We can only speculate on what may happen if (or when) such men leave behind the neutered disaffection off the internet, and start searching en masse for danger and heroism beyond the screen.

______________

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his articles.

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a recently published book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his articles.