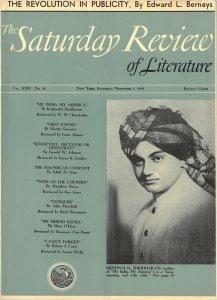

Krishanlal Shridharani was an inspiration to the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King and others

By Vidyadhar Date

Shridharani is a prominent art gallery in Delhi which I visited last week but few know that Krishanlal Shridharani was an outstanding Gujarati poet and author who lived for many years in the U.S. and was an inspiration to the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King and others.

An alumnus of Gandhi’s Gujarat Vidyapith, Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati, New York University, and Columbia University. His thesis on Gandhi’s satyagraha became the “gospel, bible” for many African American activists during the United States’ civil rights movement, points out researcher Urvish Kothari.

The Shridharani gallery is part of the well-known Triveni Sangam cultural complex of music, theatre, art and handicraft. I got to know of it mainly through Vinita Thosar, a corporate executive, during a walk in Joggers Park in Bandra. Shridharani’s son Amar is her partner and he runs the well-known center.

Shridharani had sailed to New York with scholarship funding arranged by Tagore; earned master’s degrees in economics and sociology from NYU and a PhD from Columbia; published several books; contributed countless articles to various journals, magazines, and newspapers; campaigned tirelessly to raise support for the Indian independence movement; been surveilled by British intelligence agents operating internationally; challenged racial restrictions on U.S. immigration and naturalization; and become a sought-after public speaker in a dizzying array of venues, from high society soirees to academic conferences, church gatherings, pacifist meetings, hearings with elected officials, and activist events devoted to civil rights, labor rights, and the decolonization of Puerto Rico. He had also transformed himself from a slender, serious, khadi-clad Gandhian into a flamboyant man-about-town whose elegant wardrobe and witty personality attracted the attention of American gossip columnists.

His thesis on Gandhi’s satyagraha became the “gospel, bible” for many African American activists during the United States’ civil rights movement

Malathi Iyengar, researcher, says her interest in Shridharani came about as a result of my dissertation research in ethnic studies. I was examining the transnational currents of intellectual and political exchange that flourished between African American and Indian anticolonial activists, organizers, writers, and scholars during the first half of the twentieth century. During this era, as the historian Gerald Horne notes, a multivalent web of “richly braided relations” connected “the largest ‘minority’ in what was to become the world’s most powerful nation and the largest colony of the once potent British Empire.” In the heyday of violent “Anglo-Saxon” racial-imperial domination stretching across the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania, African American and South Asian thinkers collectively constructed an activist worldview that, as historian Nico Slate puts it, “transcended traditional racial distinctions, positioning Indians and African Americans together at the vanguard of the ‘darker races.’” This worldview gained expression via constellations of interpersonal friendships, organizational partnerships, textual circulations, and jointly-coordinated events through which American and Indian anticolonial thinkers foregrounded the links between their (historically distinct yet structurally connected) struggles against white supremacy. Working together across national and imperial borders and boundaries, these activist-intellectuals “fought for the freedom of the ‘colored world,’ even while calling into question the meanings of both color and freedom.”

Krishnalal Shridharani was both a product of such transnational organizing and a contributor to it. Born in Gujarat in 1912 and educated in anticolonial schools from the age of eleven onward, he came into contact with African American texts and ideas during the 1920s and early 1930s. Indian anti-colonialists of that period took an avid interest in African American intellectual currents and educational practices. W.E.B. Du Bois, for example, was a particularly well-known voice in India; he corresponded with numerous Indian anticolonial scholars and activists, and his books and edited volumes were much read and admired on the subcontinent. Indeed, it is possible to speculatively track the influence of Du Bois though some of Shridharani’s work. This influence travelled full circle when Shridharani’s writings were enthusiastically taken up by a new generation of young African American scholar-activists during the 1940s.

Shridharani had sailed to New York with scholarship funding arranged by Tagore

While the 1942 Vogue blurb with which this essay begins mentions only My India, My America (“that best-seller last winter”), Shridharani’s African American counterparts were much more interested in some of his other books – particularly War Without Violence (1939), an analysis of nonviolent civil disobedience as a strategy within mass movements, focusing on satyagraha in the Indian independence struggle but also examining real and potential applications of similar methods in other contexts. This book of Shridharani’s is mentioned with surprising frequency in histories and memoirs of the civil rights activities carried out by African American organizers and interracial allies during the 1940s. I say “surprising” because War Without Violence was not the only satyagraha-related book available to U.S. readers at the time. The well-known white American social philosopher Richard Gregg had written several books on the subject, including the highly publicized Gandhiji’s Satyagraha or Non-violent Resistance (1930) and The Power of Non-Violence (1935). Haridas Muzumdar, a middle-aged Gandhian living in New York, had written Gandhi Versus the Empire in 1932. But none of these books are mentioned nearly as often or as passionately as War Without Violence in firsthand accounts of the civil rights activities of the 1940s.

During my visit to Triveni last week I saw two impressive exhibitions, one of sculptures of Ramachandran over the period from 1974 to the present and another was Bandwalas by veteran Krishan Khanna, one of the few survivors of the Progressive Group, now nearing 100 years. Good to note that experience of the partition of India and life in the refugee camps made him much more aware of reality than others and so he focused more on humans than on abstract art.

Krishanlal Shridharani’s wife Sundari was a dancer born in Hyderabad, Sind. She learnt dance while at Santiniketan, thereafter she joined the Uday Shankar at Indian Cultural Centre, at Almora, where she trained in Kathakali under Guru Shankaran Namboodiri and in Manipuri dance under Guru Amubi Singh. Subsequently, she joined Ginner Mawer School of Dance and Drama, London, where she learnt Greek dance. She was a nice of Acharya Kripalani, she trained a number of dancers including Hema Malini.

Also read: Activist, Scholar, Dandy

______________