Tens of thousands of citizens were arrested, some seventy-five newspapers and magazines were banned and forced to close, Black Churches were set on fire and the courts threw thousands of people into prison.

Sindh Courier Monitoring Desk

“The nation was on the brink. Mobs burned Black churches to the ground. Courts threw thousands of people into prison for opinions they voiced—in one notable case, only in private. Self-appointed vigilantes executed tens of thousands of citizens’ arrests. Some seventy-five newspapers and magazines were banned from the mail and forced to close. When the government stepped in, it was often to fan the flames.”

This was America during and after the Great War: a brief but appalling era blighted by lynching, censorship, and the sadistic, sometimes fatal abuse of conscientious objectors in military prisons—a time whose toxic currents of racism, nativism, red-baiting, and contempt for the rule of law then flowed directly through the intervening decades to poison our own. It was a tumultuous period defined by a diverse and colorful cast of characters, some of whom fueled the injustice while others fought against it: from the sphinxlike Woodrow Wilson, to the fiery antiwar advocates Kate Richards O’Hare and Emma Goldman, to labor champion Eugene Debs, to a little-known but ambitious bureaucrat named J. Edgar Hoover, and to an outspoken leftwing agitator—who was in fact Hoover’s star undercover agent. It is a time that we have mostly forgotten about, until now.

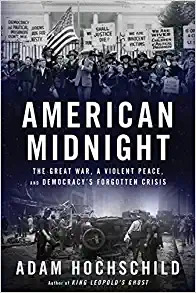

In American Midnight, award-winning historian Adam Hochschild brings alive the horrifying yet inspiring four years following the U.S. entry into the First World War, spotlighting forgotten repression while celebrating an unforgettable set of Americans who strove to fix their fractured country—and showing how their struggles still guide us today.

The book published in September last, is said to be bestseller and selected as one of the most anticipated books of Fall2022 by a number of leading newspapers. This book by legendary historian Adam Hochschild, has been described a masterly reassessment of the overlooked but startlingly resonant period between World War I and the Roaring Twenties, when the foundations of American democracy were threatened by war, pandemic, and violence fueled by battles over race, immigration, and the rights of labor.

Joanna Scutts, in a review published by New Republic (Published on October 18, 2022), says Adam Hochschild’s new book explores “what’s missing between those two chapters”—an enraging, gruesome, and depressingly timely story about the fragility of American democracy, as both institution and concept. The most prominent figure in this story is Woodrow Wilson, who enjoyed a benign-to-heroic reputation for most of the twentieth century. In bringing the United States into the war, Wilson created a sunny myth of the nation as uniquely virtuous: peace-loving, despite its violent origins, and selfless, despite the hand-over-fist profits that the war was already bringing to American factories. It was such a powerfully appealing line of thinking that “seldom would any later president depart from such rhetoric.” Most famously, Wilson urged his audience that “the world must be safe for democracy”—without anyone stopping to question whether its noble defenders had any idea what the word meant.

In his review titled ‘How World War I Crushed the American Left’, Joanna Scutts writes that according to Hochschild, it was partly belief and partly self-interest—the desire to maintain his party’s tenuous hold on power—that spurred Wilson’s determination to “crush the Socialists.” His narrative helps explain why the left has had such difficulty regaining its political ground in the United States in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, even when economic crises lay bare (again and again) the failures of capitalism. Anti-Red sentiment, from the 1910s on, was a toxic brew of racism, xenophobia, misogyny, and fear, in which rational arguments about the fair distribution of resources were comprehensively drowned.

In the decade before the war, the U.S. was home to a thriving network of radical groups and leaders. Russian-born Emma Goldman, anarchist and birth control advocate, was a wildly popular speaker (in English, Yiddish, or German, as needed) and the publisher of her own magazine. Alice Paul, head of the National Woman’s Party, was determined to hold Wilson to his promise of support. The NAACP, founded in 1909, shone a spotlight on lynching and advocated for African American civil rights. Activism against “preparedness” and war had been on the rise in left-wing circles since 1914, led especially by women like the writer and left-wing activist Crystal Eastman, head of the New York Woman’s Peace Party and executive director of the American Union Against Militarism, out of which the ACLU was later formed.

These were the groups that came under attack during the war. Emma Goldman, who drew thousands to rallies for her No-Conscription League, was arrested the very day that the Espionage Act went into effect, almost as though it had been designed for her.

The scale and the cost of these years of oppression is hard to calculate. The arrest figures, which likely climb into the tens of thousands, have never been fully counted and cannot, in any case, properly measure the invisible impact of this climate of fear: We can only guess at the true extent of the harassment, lost jobs, self-censorship, fractured relationships, and psychological damage. Yet it was the continuation and escalation of this repression after the end of the fighting that is most shocking. The Sedition Act, passed in the spring of 1918, expanded the Espionage Act to encompass still more acts of vague disloyalty and threat.

The crushing of socialism—and a new bugbear, communism—was total. The treatment of Eugene Debs was a stark illustration of the crackdown. Debs had won 6 percent of the popular vote in 1912, as the Socialists were making gains at the local and state level, threatening both Republicans and Democrats. By 1917, Hochschild notes, there were 23 Socialist mayors in office across the country, leading cities including Toledo, Pasadena, and Milwaukee. Debs opposed the war steadfastly, but he was so widely respected that the government feared directly attacking him. Instead, a disinformation campaign was launched—by whom, historians are still unsure—which implied that he had changed his position. To counter the accusations, the frail 62-year-old leader addressed his party’s state convention in Canton, Ohio, in June 1918. Careful not to advocate resisting the draft, he nevertheless roused his crowd by declaring that “in all the history of the world you, the people, never had a voice in declaring war.” Two weeks later he was arrested. When he ran for president again in 1920, it was from jail.

During these years, democratically elected socialist members of the New York State Assembly were expelled, and the House of Representatives refused to seat Wisconsin Congressman Victor Berger when he was reelected in 1918. The initial justification for silencing leftist voices, that they were sowing opposition to the war and the draft, had disappeared. In its place had arrived a generalized threat of revolution, fanned and fueled by every stray remark about ways that American society could be fairer to workers. Although most Americans today are far more familiar with the Cold War–era Red Scare, it did not come out of nowhere. The blueprint for that later crackdown was established during World War I, by many of the same actors, such as J. Edgar Hoover, who would revive it after World War II.

Adam Hochschild’s new book documents a period of thriving radical groups and their devastating suppression.

_______________

Courtesy: Amazon, New Republic