Trade between Thatta and Lahori Bandar, and Hurmuz, was well-established by the early sixteenth century, and the governors of the Estado da Índia at Goa were broadly aware of the commercial significance of the area.

Sanjay Subrahmanyam

It would appear that besides this trading presence, which naturally varied depending on the season, there was a more permanent Portuguese presence in the area with two dimensions: secular, and religious. In Thatta itself, the Carmelites had a church with two priests, to take care of some fifteen or sixteen Portuguese casados there; the priests were maintained on charity rather than money sent from Goa. In Lahori Bandar, where there were roughly equal numbers of permanently resident Portuguese, there were two Augustinians who, unlike the Carmelites did receive a handout from the Portuguese Crown and finally, there was a Crown factor resident in Thatta. The latter received no salary from the Crown, but paid forty per cent less on his goods at the customshouse than did normal merchants. This privilege he apparently abused, to carry the goods, of other Portuguese merchants through the customs-house as well. Bocarro also adds a curious note about another source of income for the Crown feitor:

Tem liberdade de poder fazer vinho que como he contra a sua ley dos mouros há muito proveito por lhe virem comprar de noite. O vinho he de jagra e de hua casca de hua arvore que chamão joto, mas o mais que vive o feitor he de sua mercancia e navio. Porem com a liberdade de feitor espanca mouros e dâ em todos, e vai gritar na casa do Governador estando em junta de Governo, e ronca que há de mandar vir a armada, e assi he obedecido… (Bocarro, idem, pag. 100).

From the middle of the seventeenth century, the importance of Thatta begins to decline in the external trade of Sindh. One reason for this was the silting up of certain channels of the Indus, which left the town less and less accessible to ocean-going ships.

After the 1630’s, however, Portuguese trade in Sind falls into some obscurity. In the early 1640’s, the English succeeded in making considerable inroads into the area, even though they were subsequently unable to keep up the pace of their expansion. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, the Thatta factory failed to meet English expectations save in brief phases. At the same time, the middle decades of the seventeenth century marked — as is well-known — a slump in private Portuguese intra-Asian trade. The effloresence of the Maskat-Kung-Basra network, to which Bocarro testifies, could not last much longer than the mid-1630’s. As Portuguese sea-power fell into decline in these years, it also seems unlikely that the factor at Thatta could have threatened to “mandar vir a armada” with any credibility. More and more, especially in the 1640’s and 1630’s, as the Mughals took an active interest in the trade of the western Indian Ocean, it would appear likely that the trade of Sind fell into the hands of Sind-based vania and other traders, and Mughal princes such as Aurangzeb and Dara.

EPILOGUE

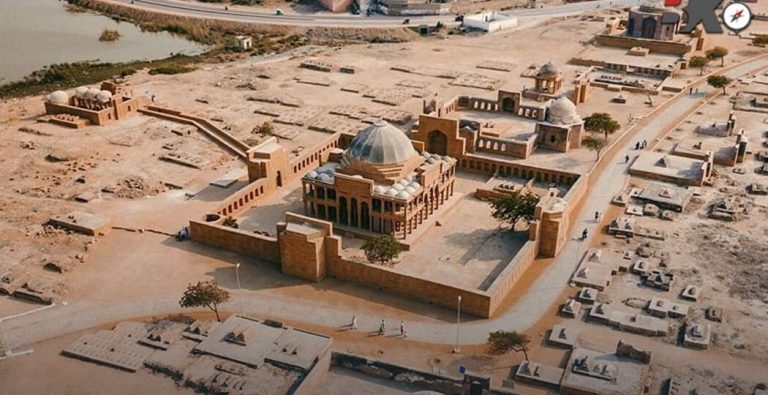

From the middle of the seventeenth century, the importance of Thatta begins to decline in the external trade of Sindh. One reason for this was the silting up of certain channels of the Indus, which left the town less and less accessible to ocean-going ships. In the 1650’s this led Prince Aurangzeb, then governor of Sind, to encourage the creation of another port in place of Lahori Bandar (which we have seen was closely associated with Thatta) and this was the port of Auranga Bandar. 16 But Thatta did not dwindle immediately into insignificance either. As late as the 1690’s, we have Hamilton’s testimony as to its size, and even in the 1740’s – when the area was invaded by Nadir Shah the town is reported to have contained some 40,000 weavers, 20,000 other artisans, and some 60,000 other residents, making a total of over 120,000.

In 1756-57, the Dutch ships Marienbosch and Pasgeld visited the area and attempted to reopen trade there, in what was to be the VOC’s last attempt in that direction. A report by W. A. Brahe and N. Mahuy, two Dutchmen on board, is preserved in the Company’s archives. It suggests that trading prospects in the region are none too good and is particularly disparaging of Thatta (where the English once more had a factory at the time, after a gap of some years). The said city (Thatta) was situated not less than two to two and a half miles inland from the river, and all goods had to be transported to the city on oxcarts and camels, with a lot of cost and trouble. He therefore feared that this would cause a lot of spillage, mainly with regard to the spices. The more so since these had been so bone-dry because of the fierce heat and the dryness which we have experienced during the voyage…”

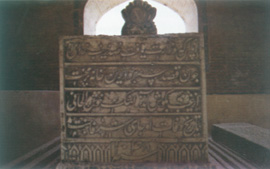

Thus, Thatta in the late 1750’s was still a trading center of some residual importance, one in which foreign merchants still sought to make a base, irrespective of the inconveniences. Perhaps this was on account of a faint memory of its bygone days of glory, or perhaps it was because the center still retained a certain administrative importance even in this period. Within three decades, even this was gone, as the newly-acceded Talpur rulers of Sindh shifted their capital north-east, to the town of Hyderabad. Meanwhile, on the maritime front the port of Marachi, which already finds mention in the account of Brahé and Mahuys was beginning to emerge into prominence. Thus, the role played by Thatta in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century was eventually divided between two urban centers: the administrative capital in the inland, and the trading town facing the sea. The town of Thatta itself became like the necropolis in the nearby Makkli hills, a place with “the habitations of the dead much exceeding in number those of the living”. (Concludes)

______________________

Courtesy: ICM Cultural Affairs Bureau (Instituto Cultural, Macau)

Click here for Part-I , Part-II