Everyone was Kashmiri first, sharing a common culture, cuisine, and language, and Muslim or Hindu second

By Jyoti Minocha

My Kashmiri Tapestry

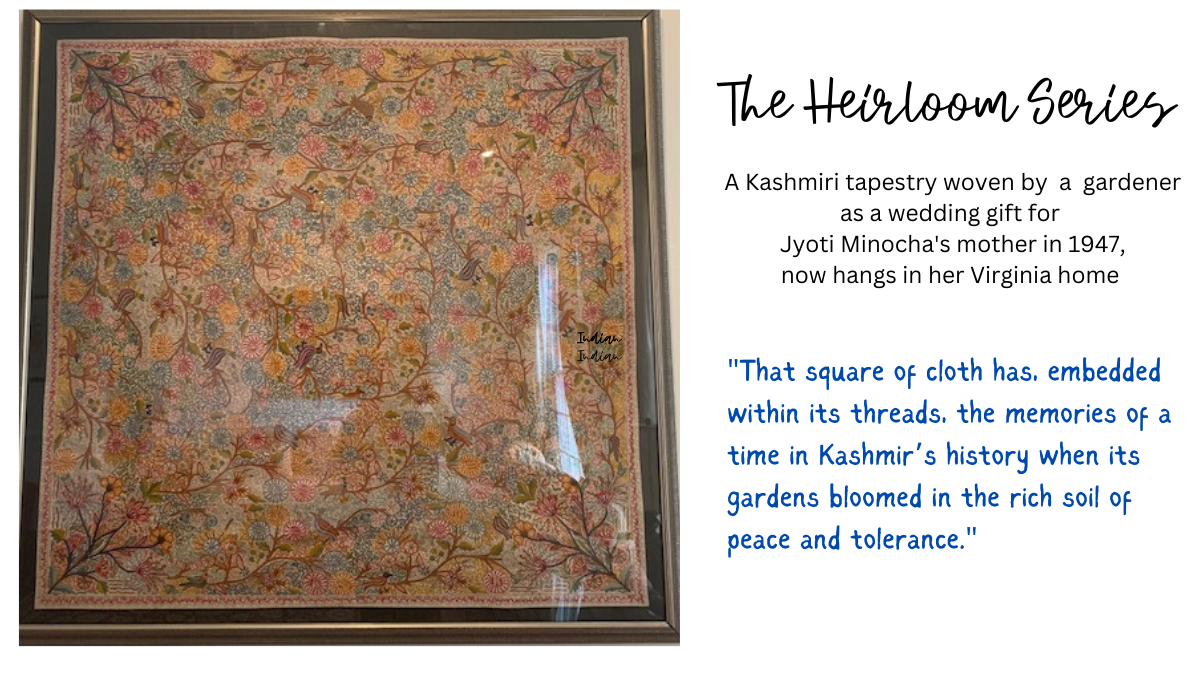

A large piece of framed Kashmiri tapestry hangs on one wall of my living room. At first glance, that’s what an observer sees— a gorgeous, square of flowers and birds embroidered with silk thread, in ornate whorls of bright colors. If one were to examine it closely, however, a puzzling contrast would create a dissonance and, eventually, a question.

While the embroidery is rich, lush, Kashmiri Kishida work, inspired by the natural beauty of the state, the ordinary looking piece of cotton sheeting it has been executed on is a far cry from the fine pashmina and wool which is usually the canvas for this exquisite needlework. Why this anomaly?

The story behind my tapestry

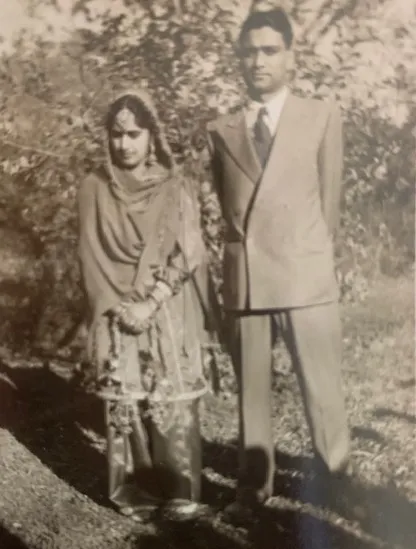

The answer to this question has a story attached to it, a family story which I treasure as much as the work itself. When my mother was growing up in Kashmir, her family had a home with a large, beautiful garden, maintained by a gardener who had tended the lawns and fruit trees for decades. As was the custom in that era, the gardener received living quarters on the premises, and he raised his young family there, including a son who was approximately my mother’s age.

My mother was engaged at the age of nineteen to my father, and as the wedding preparations began, the gardener’s son told my grandmother he wanted to give my mother a wedding present. He didn’t have the money to buy her anything; however, he had a skill, which almost every Kashmiri of that era, boy or girl, would be taught and would be required to practice on the long cold snowy winter evenings when they were stuck indoors—kashida embroidery. My grandmother tore a square from a bedsheet and gave it to the boy, and he transformed it over several months into the glory of a Kashmiri Garden in bloom.

Magic memories in my tapestry

The magic of this tapestry lies in the images it conjures up for me, of my mother’s childhood. She talked often about the Shan-gri-la she grew up in, but I can find no pictures of her childhood home. This is not surprising, considering her childhood home was abandoned during the Partition of India and Pakistan when her parents fled from Kashmir, leaving their houses and most of their belongings behind.

In my mother’s world, families were close and lived near each other. Communities were tight

If I touch the simple, soft square of bedsheet, held together by a finely worked silk thread, I can almost see an image of the gardener’s son, hunched over his embroidery every evening, a kerosene lamp next to him, the shadow of his hand moving rhythmically on the wall opposite as he pulls the needle in and out of the cloth. The servant quarters probably didn’t have electricity in 1947, but the main house did.

The house would be large and bathed in the scent of apple and pear trees, and the coils of jasmine and lavender which would grow in abundance in summer. In winter, fire from a coal stove would make the house cozy and its wooden floors would glow with warmth. I can see a parade of relatives and friends passing through the home—on festive occasions, or without any occasion.

A tapestry woven with religious harmony

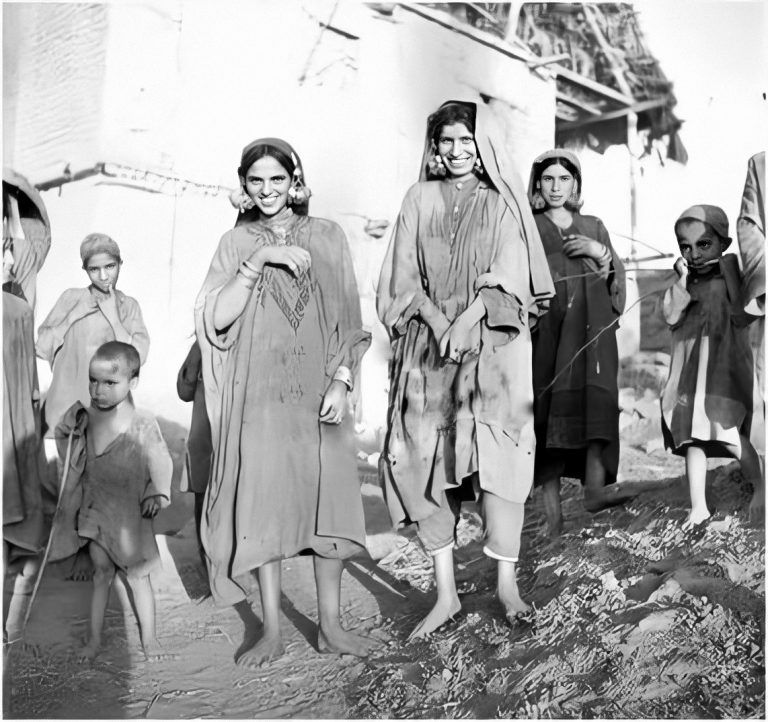

In my mother’s world, families were close and lived near each other. Communities were tight. Religion was irrelevant to relationships. Everyone was Kashmiri first, sharing a common culture, cuisine, and language, and Muslim or Hindu second. My mother’s two best friends would be running in and out of the house with her—one was a Muslim girl and the other was Sikh. My mother was Hindu.

The gardener and his son, who had tended my grandparent’s garden for decades were Muslim.

In that long-ago time, before the Partition tore the land apart, different religious communities co-existed peacefully, sang at each other’s weddings, attended each other’s festivals, and forged deep friendships

“We were inseparable,” my mother said, about her trio of girlfriends. “The fact that their religion was different never occurred to me, or even to our families. We’d lived as mixed communities, always. But when it came to dividing the country—” she trailed off.

I know she didn’t like to talk about the senselessness of the extreme violence which occurred between Hindus and Muslims during the partition of British India along religious lines. However, she was sure about one thing: the spiral of killings, looting, and abductions was ignited and stoked by ruthless politicians and greedy opportunists eager to drive the ‘enemy’ community out and occupy their vacated lands.

The wedding gift of Partition

My mother did not know what happened to her friends after her family fled to the newly minted country of India.

The wedding gift to my mother from her gardener’s son is preserved behind glass now—an official family heirloom. That square of cloth has, embedded within its threads, the memories of a time in Kashmir’s history when its gardens bloomed in the rich soil of peace and tolerance.

In that long-ago time, before the Partition tore the land apart, different religious communities co-existed peacefully, sang at each other’s weddings, attended each other’s festivals, and forged deep friendships; the memory is buried now, under the mountains of bodies and shrouds of hatred the tragedy of Partition left behind.

A piece of history

Contrary to popular misconceptions about who the perpetrators of murder and mayhem were, most people believe that friends and neighbors turned on one another, historian Guneet Singh Bhalla writes that the violence was committed by only 5% of the population, and usually by strangers.

Friends, neighbors, and employees (like my mother’s Muslim gardener and his son) reached out to help and hide those fearing for their lives.

I cling so tenaciously to this tapestry because it is a piece of my mother’s history. It’s also a piece of my history. Beyond all that, it carries a whiff of pre-Partition British India, a vision of harmony and mutual tolerance, which is increasingly being submerged under the current politics of religious division and hate being sold to a new generation.

___________________

Jyoti Minocha is a DC-based educator and writer who holds a Masters in Creative Writing from Johns Hopkins and is working on a novel about the Partition.

Jyoti Minocha is a DC-based educator and writer who holds a Masters in Creative Writing from Johns Hopkins and is working on a novel about the Partition.

Courtesy: India Currents (Posted on May 18, 2023)