The most pleasant memories in our lives tempt us to live in the past, at least for some time

Nazarul Islam

The most pleasant memories in our lives tempt us to live in the past, at least for some time. These short-lived stories bubbling from moments in time have life-lasting effects, impacting how we view our past. It is not just the memories which haunt us. And most certainly, it is not what may have been written down. Simply put, it is what you may have forgotten, and not what you must forget. Perhaps, it is something which you may go on forgetting…all your life.

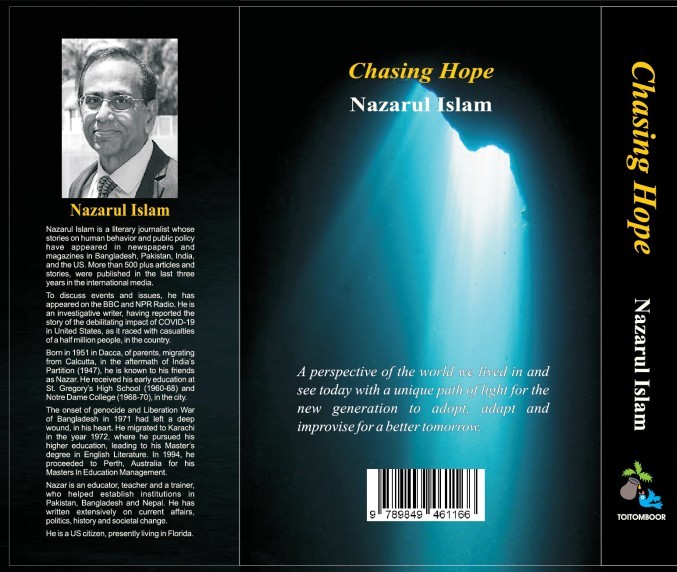

Truly, human memory is bizarre! When I first began to write my book ‘Chasing Hope’, my childhood memories of Dacca during the tumultuous year of 1971 had come flooding back to me— with all its small moments and the bigger ones. Things I hadn’t thought about in years, and the other stuff that I’ve never forgotten, hit me all together. When I began to write it all down, I realized how much I had missed my childhood years. The more I had stressed myself to dig back, the tougher it turned out for me.

So, for the first time, seven years after the massive uprising and civil war (leading to independence of Bangladesh) had ended, I gathered enough courage to return “home,” This was September of 1979. I visited Dacca, the city of my birth and my infancy. I met my former neighbors and also my school friends since childhood. I could see the familiar sights and places, just another time!

So, for the first time, seven years after the massive uprising and civil war (leading to independence of Bangladesh) had ended, I gathered enough courage to return “home,” This was September of 1979. I visited Dacca, the city of my birth and my infancy. I met my former neighbors and also my school friends since childhood. I could see the familiar sights and places, just another time!

I was particularly looking forward to reconnect with my childhood friend Tanvir Khan, to discover how we had fared—after separately being drawn to the real world of challenges, accepting new ideas, new values and the visions we were carrying —particularly, in the aftermath of a bloody war… and peace.

There is a critical error people make, which I thought I had also made, perhaps on the spur of the moment. In crisis, we hardly think or reason.

In these tumultuous seven years, all of us had obviously changed. Wars, famines, revolution, oppression and hard earned freedom alter human lives drastically. The fog of war and conflicts draw us to the safety of an imaginary net. My friends in Dacca who had survived the War of Liberation, had (in 1979) crossed over their boundaries of adolescence, to evolve into fully mature men.

Most of them had acquired a decent, well rounded professional education, and were well on their path they had opted for— leading to success and prosperity. A few had returned from foreign Universities, loaded with qualifications, energy and experience. A lot of water had flowed under the bridge. There was a lot to catch up, and share together.

Adolescence is a sensitive age. Stuck in an upheaval, thrown into a bloody revolution, one may find himself sitting on a fence divided by hatred, trying to figure out which side carries a safety net. Bad judgment could mean death or total destruction for me.

There is a critical error people make, which I thought I had also made, perhaps on the spur of the moment. In crisis, we hardly think or reason. There is the obvious pressure to get out of the mess. One doe’s not waste time, taking chances. I liked to pursue the easy option, not calculating the real consequences. There is always a fog of confusion and a lot of uncertainty in wars.

I realized in life, that my wrong choices had to bear consequences—the stressful abandonment of available mainstream choices, as the catastrophic war of ‘71 had raged, giving way to another critical period of upheavals and hopelessness. The aftermath of a fierce revolution is always challenging for both, the winners and the losers. But, lives had then mattered in 1971 for 75 million Bengali souls, plus migrant outsiders, who were caught in the same revolution.

Again, in the milieu of my indecision at the close of this war, there emerged yet another dark cloud of my indiscretion. My siblings felt insecure, because our lives were under threat. Therefore, we must find ways and means to escape to another city say, Karachi, in their search for the proverbial safety net.

To me these were the wrong choices that had thrown me and hundreds and thousands others like me, to land upon the wrong side of history and the conflict. And if it did, this would lead to a painful journey of migration, followed by my loved ones. Surely, this would impact my immediate priorities and my future life as well.

I had always wished I had walked on those dirt roads and narrow pathways of the land my mother had left for good in rural India, after the great Indian subcontinent was split in 1947.

In the last seven years, I could not pursue nor achieve what my best friends in Dacca had done, the reason: I had been chosen to lead my flock of siblings and loved ones into an unknown land, full of heart broken people—brooding and shocked by the impact of a lost war.

Faced with risks, I had to take a more responsible task of fighting the odds. My future seemed to lay somewhere in a bleak new world, that I had never visited. I had only heard the stories, many times from my grandmother. Even a diehard Optimistic, I did not rely in the plan’s feasibility. It would take a Herculean effort, traveling through three nations, sensitive borders and check points. If all went well, my siblings dream would materialize. After this, we could jump start our lives. It would take another from another painful scratch— to restore lives at some point more than a thousand miles to the west. It would be a bittersweet journey of hope.

I had always wished I had walked on those dirt roads and narrow pathways of the land my mother had left for good in rural India, after the great Indian subcontinent was split in 1947. She had migrated with my father in 1950, landing in the small city of Dacca. Separately, my uncles, aunts and grandparents had treaded different paths, to journey west, and arrive at the same destination.

They had done so at their own behest and choosing of time. Today, each one has made his or her departure to the final abode. My dead relatives now lie in the graveyards of Bihar, Dacca and Karachi. For five generations my ancestors lived as traveling nomads; they are called migrants, in today’s jargon. The reality is they migrated leaving their belongings, settled down, worked hard and prospered. Somehow, this prosperity had a short shelf life. They were uprooted, left their belongings again and moved on to the next destination. There is always a reason for every calamity,—and that is God’s will!

Decades later in the year 1981, I traveled to India, all the way to the small hamlets, and villages where my parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents were born, raised and had grown up to migrate one day, leaving their possessions and belongings to the new occupants of the homes they built.

I had set foot on the narrow pathways that were once treaded by many of my relatives, who have now passed away. I had walked those winding roads alone, this time. Often, at dusk when grey evening shadows had settled, it felt as though each one of the deceased relatives who had treaded this pathway had shadowed me, to help me not to distract myself. This was an unusual feeling which is deeply etched now, into my memory.

And that’s exactly what my quest has remained—an inquiry into my past, my people, my close relatives, loved ones who remain in my memories, making up the story of my life. The truth is that I couldn’t write about my present or the anticipated future, without writing about my life and events taking place in the small city of Dacca.

My dead relatives now lie in the graveyards of Bihar, Dacca and Karachi. For five generations my ancestors lived as traveling nomads; they are called migrants, in today’s jargon.

And even though I had carried forward my memories of a very small boy who had lived there, I have enjoyed the gift of my amazing aunt Asghari who at 98 years of age is a well-read person, literate enough to be called our family historian.

She had been my go-to person, who has filled in so many gaps in my memory. Aunt Asghari took me right back to the world of her comfort headed by her grandfather Molvi Syed Dawar Hussain, the Hakim and village wise man. He was a gifted, well-read scholar, who had compiled and retained the family tree of our last six generations—for the reference of posterity and their children that would follow!

As my book, Chasing Hope, went to the publishers, three years ago I had availed of the opportunity to return to Karachi to visit my extended family. Aunt Asghari then took me on another virtual journey of the Indian Railway, which we know built by the British colonists, nearly two centuries ago. She showed us the photographs of old train stations, and people.

She also shared some pictures of the graves of her grandparents and my great-grandparents, which she must have obtained through serious efforts. She told me so much of history that I had missed out as a child. Aunt Asghari had shared with me not only the past but she also helped me to understand the present.

So often, I am asked where my stories come from. I know now my stories are part of a continuum-my aunt is a storyteller. So were my mom and my grandmother.

And the history that Aunt Asghari showed me—the rich history that is my history—made me at once proud and thoughtful. The people who came before me had worked so hard to make this world a better place for me. I know my work is to make the world a better place for those coming after me. As long as I can remember this, I can continue to do the work I was put here to do.

On another difficult journey of writing my book, I devoted two complete chapters idolizing her for her kindness, love, affection and her sacrifices for her children. One day my mother had chimed that she had spent her toughest days of life in Karachi.

She performed her best in crisis, she washed dishes, cleaned her home, fed her children even though she was seriously incapacitated by disability and hardships. She was a brave woman. Even as I write this, I smile because my mother had the uncanny ability to always make us laugh, when she remained in pain.

I like to think I acquired a bit of her sense of humor.

I didn’t know my father well. In Dacca, he kept himself occupied in the small factory he owned. He produced an essential product for the household kitchen —kerosene fueled stoves. He had kept doing this, until his death in 1983, even though his loved ones had migrated to another country. Any letter sent to him would reach his address after three weeks.

He appeared to hide behind a feeling of guilt.

When I met him again in Dacca after a lapse of seven years. It was as though a puzzle piece had dropped from the air and landed right where it belonged. My father had remained that puzzle piece. I am trying to solve forty years after his demise in Dacca.

Gaps were also filled in by my dear friend Dr. Tanvir, who helped the journey along with pictures and stories.

When we were little, we used to say we would one day be old men together, sitting in rocking chairs remembering our childhood and laughing. We have remained passionate friends for nearly six decades today, and still call each other ‘My Blood Brother’. I hope everyone has a Forever Friend also in their life.

But at the end of the day, when I was alone, I always remembered my Blood Brother. I was always walking through these memories and making sense out of myself as a writer, in a way I had never done before.

I am often asked if I had a hard life growing up. I think my life was very complicated and very rich. Looking back on it, I also think my life was at once ordinary and amazing. I couldn’t imagine any other life. I know that I was lucky enough to be born during a time when the world was changing like crazy—and that I was a part of that change. I know that I was loved and still continue to be loved.

I couldn’t ask for anything more!

___________________

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his articles.

The Bengal-born writer Nazarul Islam is a senior educationist based in USA. He writes for Sindh Courier and the newspapers of Bangladesh, India and America. He is author of a book ‘Chasing Hope’ – a compilation of his articles.