Eventually, it was decreed that Sindhi would be taught in India with Devnagari script. While this kindly granted Sindhi parents the privilege of allowing their children to learn their mother tongue, it also separated them forever from the classics of literature of their language.

By Saaz Aggarwal

When the Hindus left Sindh in 1947, they naturally carried their language with them across the new border. However, when the Indian constitution was framed in 1950, it accepted fourteen Indian languages, and Sindhi was not one of them. It took a long legal battle before Sindhi was finally accepted as a language of the Constitution of the Republic of India on 10 August 1967. In those twenty years, the language suffered mortal blows. Those who cared, those who could not bear to imagine a world without their own language, terrified that it was imminent, tried their best to fight back. A loud babble of life-support questions arose:

The Hindus of Sindh had lost their land, what would they gain by retaining their language?

With their land gone, did they really want to restrict themselves by speaking only to each other?

Didn’t they want their children to integrate and belong to the places where they were living?

Wouldn’t it be a better use of their time and energy, in this difficult and competitive world, for the younger generation to learn other languages and read the books of other literature?

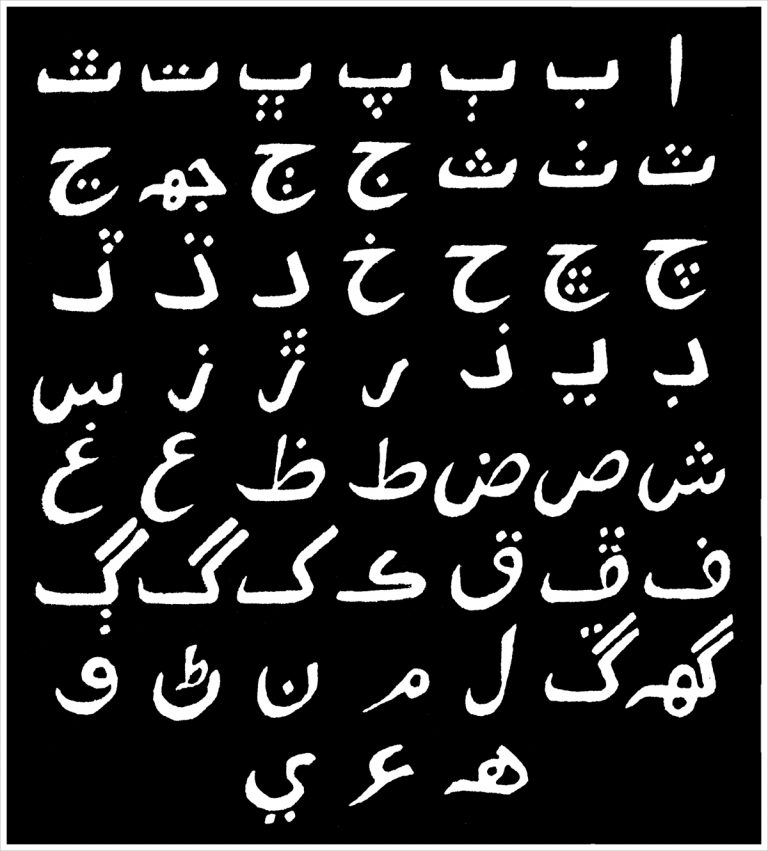

Wasn’t the Sindhi script far too complicated for ordinary people?

Why should it be imposed on the Sindhi children of the modern world for whom Sindh itself had ceased to exist?

Why should Hindus be forced to learn a Muslim script?

Eventually, it was decreed that Sindhi would be taught in India with Devnagari script. While this kindly granted Sindhi parents the privilege of allowing their children to learn their mother tongue, it also separated them forever from the classics of literature of their language.

Sindhi writers were appalled. They made every effort to express their point of view, to protest against the callous disregard of their language and culture, and demand government recognition.

Eminent lawyer Ram Jethmalani was requested to present the case. A year later, it was decided that Sindhi could be taught in the Arabic script as well.

For a scattered, shattered community, providing this choice was yet another shove away from a position where they could easily and naturally pass on their mother tongue and its rich literature to their children.

(Excerpted from book The Amils of Sindh by Saaz Aggarwal)

_____________________

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwal/Sindh Stories

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humour columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. After a career break when she had a baby, during which time she established a by-line as a humour writer, she was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989, where she launched Ascent, the highly successful HR pullout of the Times of India Group. From 1998 to 2006, she was HR and Quality Head of Seacom, an Information Technology company based in Pune. As an artist, she is recognized for her Bombay Clichés, quirky depictions of urban India in a traditional Indian folk style, as well as a unique range of offerings at the annual Art Mandai event in Pune. Her art incorporates a range of media and, like her columns, showcases the incongruities of daily life in India.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humour columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. After a career break when she had a baby, during which time she established a by-line as a humour writer, she was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989, where she launched Ascent, the highly successful HR pullout of the Times of India Group. From 1998 to 2006, she was HR and Quality Head of Seacom, an Information Technology company based in Pune. As an artist, she is recognized for her Bombay Clichés, quirky depictions of urban India in a traditional Indian folk style, as well as a unique range of offerings at the annual Art Mandai event in Pune. Her art incorporates a range of media and, like her columns, showcases the incongruities of daily life in India.