Study of funerary architecture and written artefacts of the Lawatiya Shiʿi merchant community sheds light on their mobility and settlement in Oman from Sindh and Gujarat

Mobility and Material Heritage

Most Lawatiya have no living memory or record of when the founders of the lineages to which they belong to settled in Oman from Sindh and Gujarat. Almost without exception, however, the Lawatiya belong to different related lineages. Each lineage is descended from a common male ancestor, the founder of the lineage, to whose name the Sindhi suffix -ani is added to denote descent. In some cases, the -ani lineage name is derived from a founder-ancestor who bears a typical Muslim name such as Faydalani (from Faydullah), Khalfanani (Khalfan), Jamalani (Jamal), Muradani (Murad), etc. Most other lineage names, however, are not derived from founder-ancestors with Muslim sounding names, for example Badwani (from Badu), Sajwani (Saju), Shalwani (Shalu), Najwani (Naju), etc. It has been suggested that these latter names are nevertheless corrupted from original Arabic names. The lineage name Salyani, for example, is thought to derive from Salih. What is clearly missing among the Lawatiya are the distinctive names which end with a -ji or -si suffix (such as Ramji, Dewji, Kanji, Walji or Champsi, Rattansi, etc.) commonly found among Khoja groups that settled elsewhere across the Western Indian Ocean littoral. Instead, the Lawatiya lineages tend to have a far higher prevalence of Muslim names going back to the earliest known founders of each lineage. This suggests that at least some of the Lawatiya may have emerged from a Sindhi Muslim background as opposed to more recently converted Hindu castes from Gujarat.

In addition to the -ani Sindhi suffix lineage name, the Lawatiya were also known locally as Hyderabadi. The Arabic nisba al-Hyderabadi is used in Arabic deeds and by the Lawatiya themselves throughout the nineteenth century in reference to the origins of some of the lineages of the group from the town of Hyderabad, Sindh, founded in 1768. The precise nature, however, of this connection of the Lawatiya lineages to Hyderabad, Sindh is, however, obscure. There appear to be no traces of the original Lawatiya settlement in Hyderabad, Sindh. The spoken Sindhi sociolect of the Lawatiya , known as Khojki among the Lawatiya, also appears to be closer to Kutchi today than to the central Sindhi dialect (vicholi) spoken in Hyderabad, Sindh. This linguistic shift is sometimes credited to the arrival and dominance of a second wave of Kutchi speaking Khojas that migrated to Oman directly from Kutch and merged with the original Sindhi speaking Lawatiya group that came from Hyderabad, Sindh.

The evidence of the oral traditions preserved by the Aga Khani Khojas suggests a long history of transregional mobility of Khojas between the neighboring regions of Sindh, Kutch, and Kathiawar. The earliest attested example of movement appears to be from Sindh to Kutch. It is linked to the mobility of a spiritual master (pīr) known as Pir Dadu (d. 1005/1596?). Pir Dadu is credited with converting locals in Sindh to the satpanth religious tradition that is associated today with the Khojas. Pir Dadu is said to have fled persecution in Sindh and settled in Bhuj, Kutch, taking with him converted Sindhi satpanthi families from Sindh to Kutch. The examples of movement in the opposite direction, from Kutch to Sindh, are more recent. They are either connected to the Rann of Kutch earthquake of 1819 or to famines that devastated Kutch and other parts of Gujarat in the first decades of the nineteenth century. An example is the trajectory of a certain Assa son of Danidina. Danidina is said to have been a native of Okhamandal, situated on the northern most tip of Kathiawar. In the late eighteenth century, he settled in Bhuj, Kutch. He is the earliest known individual responsible for collecting religious dues from the Khojas of Kutch and transferring them to the grandfather and later to the father of Aga Khan I in Iran. In 1819, following the Rann of Kutch earthquake, Danidina’s son Assa left Bhuj, Kutch, and trekked via Lakhpat, Kutch, to a small port on the Kutch-Sindh border known as Ramki Bazar (Rahimki Bazar) situated today in Tharparkar, Sindh. From Ramki Bazar, Assa is said to have trekked to Hyderabad where he was granted a fief by the local ruler near the Fulailee River, about a mile from the fort of Hyderabad.

The story of Assa is the earliest known fragment preserved in the Aga Khani Khoja oral tradition which attests to the presence in the early nineteenth century of Khojas from Kutch in Hyderabad, Sindh. Not much more is known about this early Kutchi Khoja presence in Hyderabad, Sindh, and its subsequent evolution. Are the present day Lawatiya descended from this historic Kutchi Khoja presence in Hyderabad, Sindh? Michel Boivin has shown that the Khoja community in Karachi emerged out of individuals with diverse caste backgrounds from Sindh and Gujarat. What united these individuals and made them “Khoja” was their conversion by a pīr to a specific religious tradition known as satpanth. The invocatory prayer (duʿa) of this religious tradition and its ritual of communion (ghat-pāt) affirmed the adherence of the Khojas to a specific chain (silsila) of Sufi masters (pīrs). Most of the pirs of the Khoja silsila in Sindh and Gujarat traced their lineage as sayyids (descendants of the Prophet) to a fourteenth century Sufi buried in Multan, Pir Shams Sabazawari Multani (d.757/1356). In the nineteenth century, however, following the arrival of Aga Khan I in Sindh from Iran in 1843, the charismatic authority of local pīrs claiming descent from Pir Shams declined among most Khojas who recognized Aga Khan I as their pīr and later as a Nizari Ismaʿili imam. Khojas, who chose not to recognize the Aga Khan I as a Nizari Ismaʿili imam, identified themselves as Sunni or Twelver Shiʿi, and, in so doing, also abandoned the old Khoja silsila of pīrs and ritual of communion.

The script is simply referred to by the Lawatiya as “Sindhi” not “Khojki Sindhi”. The term Khojki is used by the Lawatiya to refer to their spoken sociolect

It is likely that a similar integrative process occurred in Hyderabad, Sindh, prior to the arrival of the Aga Khan I. Recognition of the spiritual authority of a specific chain of pīrs through the invocatory prayer (duʿa) and ritual of communion allowed a diverse group of individuals to become Khoja. It meant that individuals such as Assa arriving in Sindh from Kutch and local Sindhis known as lotias/lutiyah could come together to form the basis of the Khoja community in Hyderabad, Sindh. It is this new Hyderabadi Khoja group that would later become significant in Oman and elsewhere in the Persian Gulf and use the Arabic nisba al-Hyderabadi. Further linguistic research on the Lawatiya spoken sociolect might be able to shed light on the complex Sindhi-Kutchi confluence that led to the emergence of the Lawatiya community. This confluence probably occurred both in Hyderabad, Sindh itself and in Matrah, Oman where the Lawatiya or Lutiyah, who by now were also known as Khojas and Hyderabadis, had already settled. The example of the formation of Khoja communities elsewhere in the Western Indian Ocean offers comparable examples of a Kutchi-Kathiawari convergence. In the latter case Kutchis and Kathiawaris from diverse agricultural and artisanal caste backgrounds also come together in an integrative process that occurred after the conversion of such individuals to satpanth and their adherence to a silsila of pīrs. It is only in the nineteenth century that such diverse Khoja groups, including the Lawatiya, would become associated mainly with trade.

Tracing the movement of the individual founders of the Lawatiya lineages from Sindh and Kutch to Oman is also made more difficult because in some cases arrival in Oman was preceded by initial settlement in the ports of Makran (coastal zone of Iranian and Pakistani Baluchistan), the Persian Gulf, the Trucial States or even further afield in Bombay. Lawatiya lineages founded by individuals that had initially settled in Chabahhar in Iranian Baluchistan are known as “Chobari”, while those that had settled in Bandar Lingeh (Hurmuzgan province, Iran) in the Persian Gulf are called “Lingewari”. There are also examples of arrival and settlement in Oman that occurred via the Trucial States. For example, one of the early leaders of the Lawatiya community in Matrah, Oman, Hajj Sulyman Qurbun (Qurban ʿAli), is said to have received Hajj ʿAbdullatif b. Fadil (1851-1931) in Matrah after he arrived, accompanied by others, from Raʾs al-Khayma (United Arab Emirates) following his father’s death in 1857. These multiple transregional mobilities of the Lawatiya ancestors as we shall see, is reflected in their material heritage.

Lawatiya Graves

The funerary architecture of the Lawatiya reaffirms the connections of the group to Sindh and Kutch. The oldest extant Lawatiya graves are found in the Lawatiya cemetery in Jibroo, a suburb of Matrah.

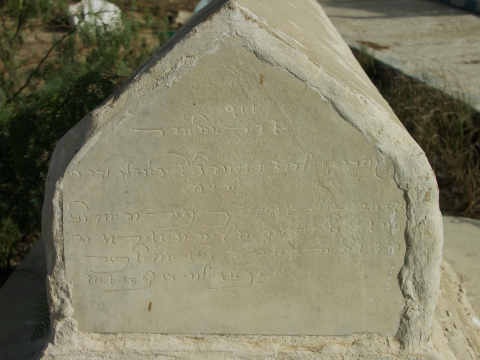

The dead body was buried inside a grave pit which was sealed by a rectangular slab. Above this slab a series of additional rectangular slabs were added. The length and width of the additional slabs decreases progressively from the lowest slab to the top slab creating a series of steps in the form of a pyramid. Above the topmost rectangular slab, a qalamdān was added. This Persian term literally means a box or case for storing a pen. The ends of the qalamdān in the grave are in the shape of a pointed arch with two centers. In other cases, the shape of the two ends appears to be closer to an equilateral arch. In most of the surviving examples of such graves from the Lawatiya cemetery in Jibroo, however, the qalamdān is no longer extant above the rectangular slabs. It is impossible to confirm its exact shape or whether the qalamdān had any inscriptions. We know, however, from a surviving example of similar “qalamdān-step” graves in the Khoja Miyan Shah cemetery in the Lyari district of Karachi that an inscription in the Sindhi script associated with the Khojas was usually recorded onto one of the ends of the qalamdān.

The practice of adding an inscription onto the qalamdān is also attested in the graves of the Twelver Shiʿi Khoja cemetery in Kera, Kutch. The Twelver Shiʿi Khoja graveyard in Kera has many “qalamdān-step” graves built with a above a series of rectangular stone slabs. These graves resemble the form of the Lawatiya “qalamdān-step” graves in Jibroo. In Kera, however, the inscriptions at the end of the qalamdān are in Gujarati script.

In both the Karachi example and in Kera, it is not clear if the qalamdān inscriptions were part of the original graves or added during subsequent renovations. Besides the Lawatiya cemetery in Jibroo, in Oman, “qalamdān-step” graves have also been found in the district of Rustaq, in the Al-Batinah region of northern Oman, and in Lughan, a quarter of Muscat outside the walls, beyond Tuyan and al-Rawiyah Fort, west of Hillat al-Shaykh, on the way to al-Wadi al-Kabir.

According to the local inhabitants in Rustaq today, these graves belong to the Lawatiya. This is by no means certain. In the case of Lughan, Lorimer notes at the beginning of the twentieth century, that the quarter was inhabited by Baluchis, which suggests that these graves belong to Baluchis. In Sindh and Baluchistan, however, Baluchi tribes are known to have used a far more elaborate style of the qalamdan-step form known as “Chaukhandi” which flourished between the sixteenth-eighteenth centuries. Large numbers of such Chaukhandi graves are found in graveyards in Baluchistan and in Sindh, the most spectacular examples are in the UNESCO world heritage Makli necropolis in Thatta, lower Sindh. Unlike the simple qalamdan-step graves, Chaukhandi graves involved the use of multiple intricately carved stone slabs. It is therefore possible that the Lughan graves did not belong to Baluchis but to Sindhi Muslims. A colophon of a Quran copied in 1179/1765-1766 by a certain al-Sayyid Muhammad b. Fadil al-Sindhi in Muscat, suggests there was a Sindhi Muslim presence in Muscat. It is likely that the Lughan and Rustaq graves are related to this Sindhi Muslim presence. It is difficult, however, to determine any relationship, other than similar grave architecture, between this Sindhi Muslim presence in Lughan (Muscat) and Rustaq and the Lawatiya lineages who are known to have historically settled in Matrah and were buried in the cemetery in Jibroo.

Written Artefacts in “Khojki Sindhi” Script

Besides Lawatiya graves, surviving written artefacts in “Khojki Sindhi” script among the Lawatiya also point to the historic connections of this group to Sindh and Kutch. Khojki Sindhi script is one of numerous mercantile scripts derived from Brahmi used to record Sindhi. The script is simply referred to by the Lawatiya as “Sindhi” not “Khojki Sindhi”. The term Khojki is used by the Lawatiya to refer to their spoken sociolect. This confirms Shafique Virani’s recent suggestion that the use of “Khojki” and “Khojki Sindhi” in reference to the Sindhi script associated with the Khojas is a neologism. In order, however, to distinguish this script from comparable Sindhi scripts associated with other communities, I have chosen to retain the use of Khojki Sindhi.

So far, Khojki Sindhi script has mainly been studied in relation to its usage to record the ginan genre of devotional hymns of the Khojas of South Asia. The Lawatiya, however, preserve several manuscripts in the script which record elegiac poetry in Sindhi (marsiyo) relating to the martyrdom of al-Husayn. In addition, the Lawatiya have also preserved examples of how Khojki Sindhi script was used for funerary inscriptions on gravestones and for different types of accounting records, business letters and commercial registers. (Continues)

___________________

Zahir Bhalloo – Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), Universität Hamburg

Research for this paper was generously funded by the Sultan Qaboos Higher Centre for Culture and Science (SQCCS) through an Oman Research Grant visiting fellowship at the Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. An earlier version of the paper was presented online on 8 July 2021.

Courtesy: Open Edition Journals

Click here for Part-I

Alessandro Carlson