Study of funerary architecture and written artefacts of the Lawatiya Shiʿi merchant community sheds light on their mobility and settlement in Oman from Sindh and Gujarat

Zahir Bhalloo

Gravestones

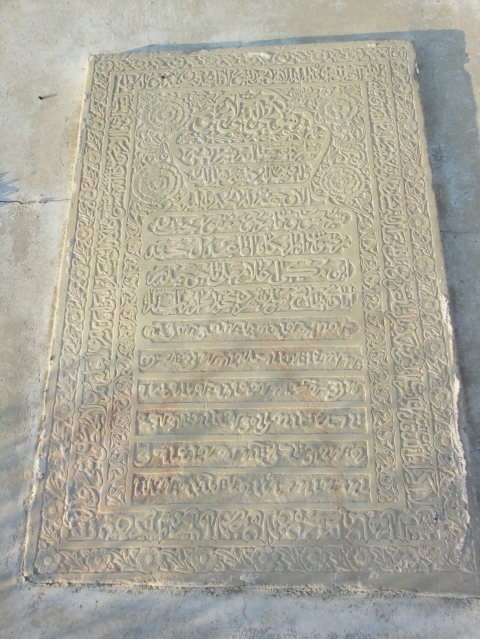

Besides the “qalamdān-step” graves, the Lawatiya cemetery in Jibroo also contains at least five gravestones made in the late nineteenth century. These gravestones contain bilingual Sindhi and Persian inscriptions. The Sindhi element is written in Khojki Sindhi script, while the Persian part is written in nastaʿliq script. Two gravestones appear to be related to a single family. The first records the death of Rubab wife of Hajji Muhammad ʿAli Hyderabadi on 23 Rabiʿ I 1315/22 August 1897 (fig. 5) and the second records the death of his daughter Shahi in the following year on 19 Shaʿban 1315/13 January 1898. A third gravestone records the death of Fatima bt. Hajji ʿAbd al-Rasul Qasim Hyderabadi on 26 Shaʿban 1317/30 December 1899. These three gravestones are simple in style and are smaller in size than the remaining two gravestones.

The remaining two gravestones are far more elaborate. They were probably commissioned by wealthy Lawatiya merchants. The Persian element consisting of honorifics in these gravestones is longer. The Persian is also inscribed in Arabic naskh script not Persian nastaʿliq used for the simpler gravestones. There is also an additional Arabic element in these gravestones, mainly pious Arabic formulas such as huwa l-ḥayy al-ladhī lā yamūt (He God is the Everlasting who does not die) or verses from the Qurʾan relating to the inevitability of death such as Q: 28:88: kullu shayʾin hālikun illā wajhahu (everything is perishable except his (God’s) Face). The first gravestone records the death of Safura daughter of Hajji Fadil Hyderabadi on 25 Shawwal 1298/20 September 1881 (fig.6). The artisan who produced the gravestone (ʿAbd al-Khan Shuma? Birdi?) has recorded his name at the top. The second gravestone is dated the beginning of Dhu l-Hijja 1312/May 1895. It records the death of Aqa ʿAbdulu Muḥammad Mukiya Ghulam ʿAli Hyderabadi described as the Hyderabadi merchant (tājir-i ḥaydarābādī) (fig. 7). It is not clear where these gravestones were produced. Given the usage of Persian, it is likely they were produced for individuals belonging to Lawatiya lineages that had initially settled in Iranian ports along the Persian Gulf coast such as Bandar Lingeh or the port of Chabhar in Iranian Baluchistan, before eventually settling in Matrah, Oman.

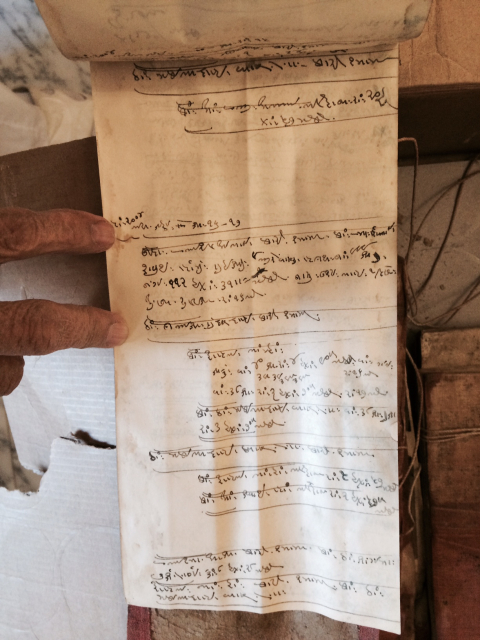

Devotional Texts

In their ritual performance, the Lawatiya rely on a corpus of Shiʿi devotional poetry in Arabic, Persian and Sindhi relating to the martyrdom of the grand-son of the Prophet, al-Husayn in Kerbala in 680 A.D. The Sindhi poetry recorded in Khojki Sindhi script consists of elegies known as marsiyo. These elegies were recorded into long vertical pothi manuscripts, which resemble the registers used to record accounts (see fig. 10 below). The exact number of such surviving manuscripts among the group is not known. These manuscripts are sometimes even used in actual recitations of the marsiyo by the Lawatiya today. The only manuscript I have examined so far is dated 1326/1908-1909 and belonged to ʿAbd al-Ghafur al-Hyderabadi. Some of the elegies recorded in Khojki Sindhi script in this manuscript can be traced to the work of the Sindhi poet of Sehwan Sharif, Sabit ʿAli Shah Kerbalai (1740-1810).44 There is some evidence to suggest that the Khojas in Kutch also preserved similar manuscripts containing the marsiyo of Sabit ʿAli Shah.

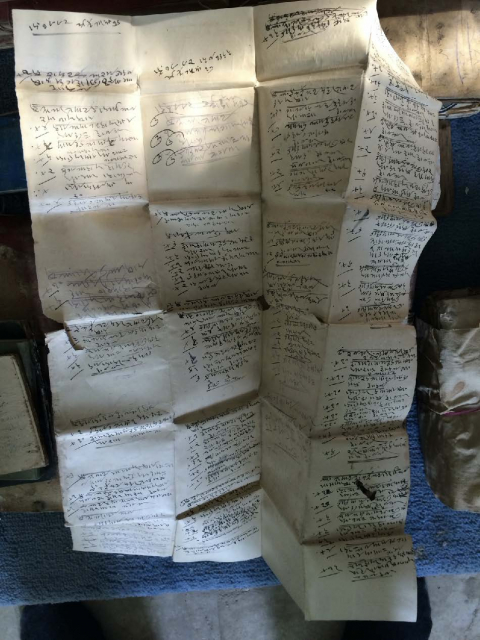

Accounting Records, Letters and Registers

Besides gravestones and devotional texts, the third type of written artefact among the Lawatiya in Khojki Sindhi script are commercial accounting records, letters, and registers. Khojki Sindhi was used as a mercantile script among the Lawatiya well into the 1980s before falling into disuse. The Lawatiya appear to be the only known Khoja group that preserved the usage of the script in its mercantile variant into the twentieth century. During fieldwork in Muscat, I came across the archive (fig. 8) of a textile broker active in the Matrah suq, ʿAli Mukhtar b. ʿAli Muhammad Salih al-Lawati (al-Hyderabadi) (d. 1988) in the attic of his brother.46 Bundles of documents and twenty-two registers in Khojki Sindhi script were crammed into an old suitcase and a wooden chest (fig. 9). Many of the registers (fig. 10) and documents (fig. 11) were wrapped in cotton cloth. Given the fact that there is almost no research on the usage of the Khojki Sindhi script in its mercantile form, this corpus of material is of outstanding historical significance. It is likely that many of the other Lawatiya lineages in Oman also preserve similar commercial documentary corpora in Khojki Sindhi script. This includes Arabic deeds known as waraqa with witness clauses in Khojki Sindhi script.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study has been to shed light on Oman’s transregional connections to Sindh and Gujarat through the example of the mobility of the Lawatiya Shiʿi Muslim presence and its material heritage. Oman has ancient historic ties to Sindh and Gujarat. The mobility and settlement of the Lawatiya is only one recent episode of a longue durée history of movement and settlement between these regions.48 The Lawatiya are, moreover, not the only diasporic group that settled in Oman from Sindh and Gujarat. The Hindu merchant communities of Oman also moved to Oman from Sindh and Gujarat, while the Sunni Muslim Zadjali community is also known to have ties to Sindh. The material heritage of the Lawatiya points to different transregional mobilities which resulted in the formation of this social group. These mobilities involved movement between Sindh and Kutch itself, and across the coastal zones of Baluchistan, southern Iran, the Trucial States (today the United Arab Emirates), and Oman. Not surprisingly, culturally, and linguistically, the Lawatiya have been shaped through their mobilities by Sindhi, Kutchi, Baluchi, Persian and Arabic. This is also reflected in their material heritage in terms of their distinctive funerary architecture and written artefacts.

The Lawatiya example is significant as it demonstrates that the historic emergence of Khoja groups brought together individuals with different caste backgrounds through a complex integrative process that occurred from the late eighteenth century onwards. This integrative process took place within the context of transregional mobility and involved repeated shifts in adherence of the newly formed group to rival spiritual genealogies. The Lawatiya of Oman are the only known Khoja group who have retained the name of the original caste, lotia/lutiyah, to which some of the founders of the Lawatiya lineages belonged. In all other Khoja groups the pre-Khoja caste or group names have not been preserved.

Besides the integrative process that led to the emergence of the Lawatiya Khoja group, it should be noted that the Lawatiya have also integrated over time, through marriage, individuals from the Baharina Arab and Iranian Shiʿi communities with whom the Lawatiya share the same Twelver Shiʿi religious identity. What is less clear are social links, if any, past or present, between the Lawatiya lineages and the Sunni Muslim Zadjali or Baluchi communities in Oman. More recently, there are also examples of intermarriage between the Lawatiya and Omani Ibadhis. These new integrative processes have taken place alongside new transregional mobilities of the Lawatiya within the Middle East, as Lawatiya migrate and return to Oman after work or study in places such as Iraq, Kuwait, and other parts of the Gulf. The result is the emergence of an entirely new generation of Lawatiya, many of whom have lost the ability to speak the Sindhi sociolect of the group. For these Lawatiya, there is little memory of a shared Khoja past. Their connection to South Asia, is understood, if at all, through the Banu Sama b. Luʾayy narrative of their tribe’s origins in Oman and its subsequent return to Oman from Sindh. Only among older Lawatiya, is there still some consciousness of links with other Khoja groups, and a desire to interpret Lawatiya difference, while, transmitting at the same time, the few material, ritual, or linguistic remains of a transregional heritage that separates the Lawatiya of Oman, both from other Khojas, and from Arab and Iranian Shiʿis of the Gulf region. (Concludes)

_____________________

Zahir Bhalloo – Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), Universität Hamburg

Research for this paper was generously funded by the Sultan Qaboos Higher Centre for Culture and Science (SQCCS) through an Oman Research Grant visiting fellowship at the Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), Berlin. An earlier version of the paper was presented online on 8 July 2021.

Courtesy: Open Edition Journals

Click here for Part-I and Part-II