[This article explores the emergence of a network of young intellectuals from rural and mostly peasant background, and focuses on two pioneers of Sindhi nationalism and Sufi revivalism: G.M. Syed and Ibrahim Joyo. Influenced by Gandhian as well as Marxist ideas on social reform and national identity, these two leaders transformed the annual urs celebration at local shrines into commemorations of the martyrs of Sindh. The article traces their relationship as well as their pioneering role as political leaders, education reformers, and teachers. Analyzing their ideas as a particular form of Islamic reform, the article discusses the way they adapted and innovated the existing cultural ideas on Islamic nationalism, ethnicity, and social justice]

By Oskar Verkaaik

IBRAHIM JOYO AND THE YOUNG SINDHI INTELLECTUALS

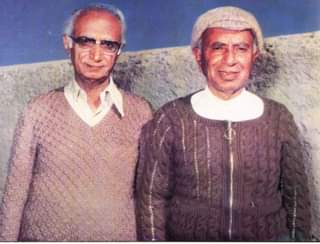

Ibrahim Joyo was born in 1915, twenty miles from the village where G.M. Syed was born. His father was a peasant but also acted as a middleman between the landlord and the other peasants. On top of this, he owned some land of his own. This gave him an important position in the village where the peasants and artisans were Muslims, and shopkeepers and traders were Hindus. The landlord, a Syed, was also the spiritual leader.

However, Joyo’s father died when Ibrahim was two years old. Ibrahim, nonetheless, got the opportunity to go to the primary school in the village. After five years, he went to the school G.M. Syed had founded in his home village. G.M. Syed also arranged a scholarship for him that enabled him to go to the Sindh madrassah in 1932. There he stayed for two years, living in G.M. Syed’s house in Karachi, known as Hyder Manzil. This house became a meeting place for students connected to G.M. Syed, and later, after 1958, it would become a center of the Sindhi movement emerging around G.M. Syed and Ibrahim Joyo.

However, Joyo’s father died when Ibrahim was two years old. Ibrahim, nonetheless, got the opportunity to go to the primary school in the village. After five years, he went to the school G.M. Syed had founded in his home village. G.M. Syed also arranged a scholarship for him that enabled him to go to the Sindh madrassah in 1932. There he stayed for two years, living in G.M. Syed’s house in Karachi, known as Hyder Manzil. This house became a meeting place for students connected to G.M. Syed, and later, after 1958, it would become a center of the Sindhi movement emerging around G.M. Syed and Ibrahim Joyo.

It became Joyo’s ambition to become a teacher at the Sindh madrassah himself and he managed to get another scholarship to do his bachelor in teaching in Bombay. During the two years he spent in Bombay, he got in touch with Marxist journalists and writers, writing in English, most of them from Bengal. They were opposed to both the Congress Party and the Muslim League. This was an important influence on Joyo’s thinking. He became a critic of communal politics, that is, the religious identity politics that pitted Hindus against Muslims, and vice versa. True to Marxist doctrine, he considered religion an instrument of class politics and economic exploitation. For him, the main struggle was a class conflict, but capitalists as well as landlords used the religious sentiments of the people in order to keep the underprivileged masses divided. Back in Sindh, he became a teacher at the Sindh madrassah. He also started a magazine called Freedom Calling, which argued for supporting the British during World War II in return for independence.

In 1947 he published a little book called Save Sind, Save the Continent (From Feudal Lords, Capitalists and their Communalisms), with a foreword by G.M. Syed. In this book he condemns the landlords (Zamindar) and Pirs for exploiting the peasants. He condemns the peasants for living like slaves, while on their part tyrannizing their women. ‘‘The only duty they know is to work like bullocks for their landlords and money-lenders, to touch the feet of their Zamindar-Masters and Pirs, and worship them literally as living gods, and lastly to instruct their children to do likewise’’. This is particularly pitiful, he goes on, because these peasants are Muslims and Islam is a liberating religion. He thus gives his own twist to the notion, widespread among reformists of various kinds, that the true message of Islam has been forgotten with the result that the Muslims live in misery. For Joyo, however, the main fight is not with European powers. The main fight is against oppressive landlords, backward spiritual leaders, and Hindu moneylenders, a fight that can only be won if the Muslims return to the Islamic message of social justice and equality.

Besides, Joyo argues in his book, the recent Punjabi settlers, who came to Sindh after the completion of the irrigation works in the 1930s that turned vast desert areas into agricultural lands, are to blame for the misery of Sindh’s peasants. He blames these settlers for being ignorant of Sindhi culture and especially of the eighteenth-century poet Shah Abdul Latif, who was the first poet to sing in the Sindhi language. He also blames them for obstructing the cultural de-colonialization of Sindh after Sindh’s provincial autonomy in 1936. He writes:

Poor G.M. Syed, when he was the Education Minister, had issued or was on the point of issuing orders that every non-Sindhee in Sindh must learn Sindhee within a stipulated period of time. This, at that time, raised such a vehement noise everywhere among the circles concerned, as if somebody was asking them for giving up their religion.

The ‘‘circles concerned’’ were of course the Punjabi settlers. In short, in Joyo’s analysis the notion of class struggle, Islamic revivalism, and early Sindhi nationalism come together in an optimistic belief in ‘‘the river of Progress’’, in which the Sindhi Muslim peasants constitute the progressive potential, struggling against the reactionary forces of landlords, traditional religious specialists, and recent Punjabi immigrants. Recognizing the class and national differences between Muslims, he also criticizes Muslim nationalism, saying that ‘‘to talk of Muslim nationalism would be as meaningless and self-contradictory as to talk of world-Nationalism, for Islam represents Universalism, and can be embraced by any one of the hundred and one Nations of the world’’.

At the time of publication the book failed to get much attention in Sindh as the group of leftists was still very small. Joyo saw it as his first task to form a revolutionary vanguard of young Sindhi students and intellectuals.

‘‘It is to their youth’’, he writes, ‘‘more specially their student community, and to their middle-class Intelligentsia, that a people always turns for rescue, in times of danger, sorrow or distress. In this respect, the people of Sindh appear to be a little unfortunate’’, as there was as yet hardly a Sindhi student community to speak of. His ambition to be a teacher was therefore ideologically informed. At the Sindh madrassah in Karachi, and later at Sindh University in Hyderabad, he left his ideological mark on several Sindhi students from peasant and artisan backgrounds.

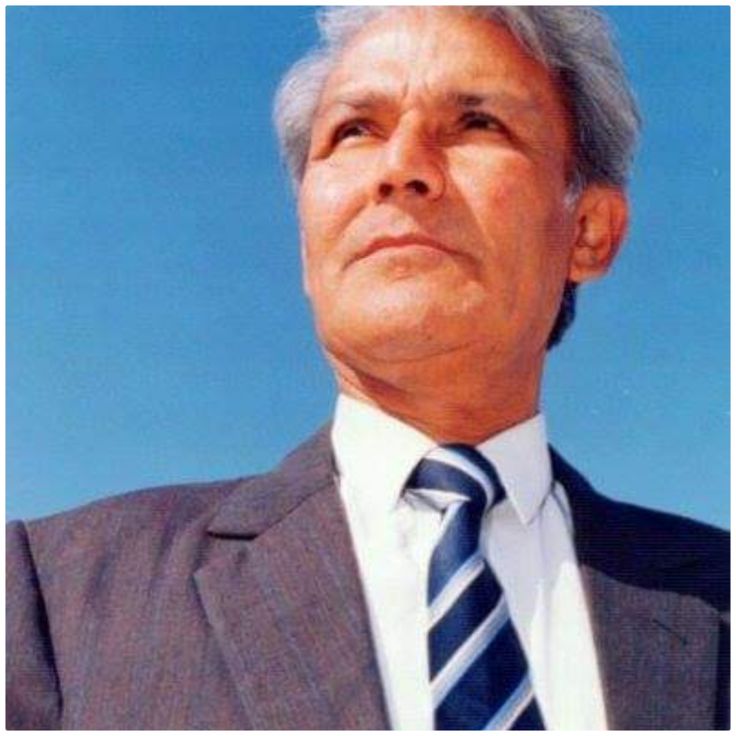

One of them was Hyder Bakhsh Jatoi, who became the president of the Hari Committee in 1948. He also was a poet, writing poems in Sindhi in praise of the great river Indus or Sindh. Another student of Joyo was Rasul Bakhsh Palijo, who graduated from the Sindh madrassah in 1948. He became a schoolteacher in the town of Thatta and later became a lawyer defending Sindhi students and separatists in many controversial court cases. In the 1960s, Palijo was one of the most radical leaders of the Sindhi movement protesting against the military regime of General Ayub Khan.

One of them was Hyder Bakhsh Jatoi, who became the president of the Hari Committee in 1948. He also was a poet, writing poems in Sindhi in praise of the great river Indus or Sindh. Another student of Joyo was Rasul Bakhsh Palijo, who graduated from the Sindh madrassah in 1948. He became a schoolteacher in the town of Thatta and later became a lawyer defending Sindhi students and separatists in many controversial court cases. In the 1960s, Palijo was one of the most radical leaders of the Sindhi movement protesting against the military regime of General Ayub Khan.

A third vocal leader of the Sindhi movement was Jam Saqi, leader of the Sindhi student movement in the late 1960s, who later became the leader of the Communist Party. Both Jam Saqi and his father had been students of Ibrahim Joyo, the father at the Sindh madrassah in Karachi, Jam Saqi himself at Sindh University near Hyderabad. Like G.M. Syed’s house in Karachi, Joyo’s residence in Hyderabad became a meeting place of Sindhi separatists and leftists from the 1960s onwards.

_______________________

Oskar Verkaaik is Assistant Professor at the Research Center for Religion and Society, University of Amsterdam, and head of the branch office of the International Institute for Asian Studies. He is the author of A People of Migrants and a popular book in Dutch based on his experiences in Pakistan.

Courtesy: The International Institute of Social History, one of the largest archives of labor and social history in the world. Located in Amsterdam

Click here for Part-I, Part-II, Part-III