[From imperial ‘unhappy valley’, to decapitated province, commercial capital, and 21st century megacity, this article reflects on relations of separateness and connectivity between Sindh and its capital city Karachi. These culminated in Pakistan’s post-Independence years, in official and political language, governances of national, provincial and city division, and political rhetoric and violence. The article asks what else might be uncovered about their relationship other than customary alignments and partitions between an alien urban behemoth and a provincial periphery. It develops a topographical view to refer to the physical arrangement of environments but also people’s profane, spiritual and political connections and losses involving place and dwelling]

By Nichola Khan

Foreshadowing Pakistan’s Independence, the English scholar D.H. Horley, having learnt Sindhi, published selected translations from the Shah Jo Risalo (Message of Shah), a compendium of works by the revered Sindhi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689–1752) (Horley, 1940). Interwoven through Horley’s translations of the sung ballads (surs) is the classical tradition of Sufi mysticism and theme of seeking God through renouncing the ego. Through evocations, laments, and joyful exultation, the poetry invokes a symbolic topography of wind, water, earth, rain, rivers, deserts, and animals that flows uninterrupted through the people and land. Horley’s selection Sur Samandi urges sailors and fishermen to sail on the waning monsoon winds and worship the Deep ocean, a metaphor for God. Horley sought, in the European tradition, to capture Sindh’s immemorial beauty in these poetic ballads about romance, suffering, and the land – his intellectual and cultural sojourn buttressed by the British conquest of Sind in 1843.

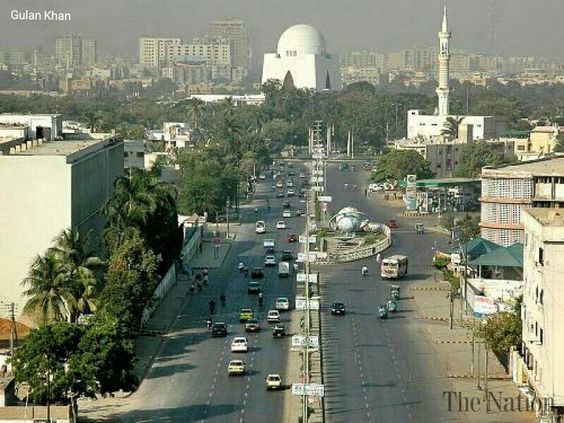

Deeply contextualized by older Sindhi histories of military invasion, cultural assimilation, and riposte, British rule saw Kurrachee leap from what militaryman Baillie (1839/2013) describes a ‘miserable native fortress into a civil town of considerable size’, forcing the ancient capital Hyderabad to abdicate. When the British relinquished India in three parts a century later, Pakistan was born from the ‘two nation theory’ that Hindus and Muslims could not co-exist. Mohammad Ali Jinnah established Urdu, symbol of Islamic identity in Northern India, as the national language. West of the Indus Delta on the Arabian Sea, Karachi became Pakistan’s first capital until 1959. Karachi, a Sindhi-majority city, became an Urdu-speaking ‘refugee city’ of Indian Muslims who populated ‘camps’, squatter settlements, and the properties of a million fleeing Hindus (Ansari, 2005). This third largest ever-recorded refugee migration appositely disrupts the contentious silence about refugees in urban studies, and images of refugee settlements situated in spaces of urban marginality and temporariness (Sanyal, 2014).

Sindh province is now predominantly ethnically Sindhi, home to 94% Pakistan’s Hindu community (c. 3 million) (http://www.pakistanhinducouncil.org). Its northern and central districts comprise the heartland of Sufi Islam in Pakistan. Karachi’s unruly, exponential growth from 450,000 to 1.137 million by 1951 continued. With a population of over 11 million, and much higher unofficial estimates, Karachi is also the world’s largest Muslim city, the world’s seventh largest conurbation, and projected to become the world’s fourth most populous city by 2030 (World Population Review 2020). Many recent large-scale infrastructural and development projects in Karachi, funded by Chinese loans and US aid and loans, disrupt ideas of imperialism and Empire as essentially Western and align with major imperial reconfigurations of urban planetary power involving China in Africa, Asia, and Europe (Sidaway et al., 2014). They reflect a complex urbanity comprised of colonial and postcolonial contradictions, fractured social scales, identity politics linked to place, and global neoliberal imaginaries of a world-class city linked to replications of Dubai or Singapore (Anwar, 2014).

Sindh province is now predominantly ethnically Sindhi, home to 94% Pakistan’s Hindu community (c. 3 million) (http://www.pakistanhinducouncil.org). Its northern and central districts comprise the heartland of Sufi Islam in Pakistan. Karachi’s unruly, exponential growth from 450,000 to 1.137 million by 1951 continued. With a population of over 11 million, and much higher unofficial estimates, Karachi is also the world’s largest Muslim city, the world’s seventh largest conurbation, and projected to become the world’s fourth most populous city by 2030 (World Population Review 2020). Many recent large-scale infrastructural and development projects in Karachi, funded by Chinese loans and US aid and loans, disrupt ideas of imperialism and Empire as essentially Western and align with major imperial reconfigurations of urban planetary power involving China in Africa, Asia, and Europe (Sidaway et al., 2014). They reflect a complex urbanity comprised of colonial and postcolonial contradictions, fractured social scales, identity politics linked to place, and global neoliberal imaginaries of a world-class city linked to replications of Dubai or Singapore (Anwar, 2014).

This article takes Karachi as a useful optic to think topographically about continuities of colonialism and imperialism, and crisis and fracture in post-colonial South-Asia; the imperial and ecological dynamics of planetary urbanizations that infuse them; and ways analytic attention to local, national, and regional crises can resist theoretical universalism regarding the contemporary urban. Specifically, it draws examples from historical and contemporary, and real and imagined modes of connectivity and separation between metropolis and province. It builds on shifting intensities of multiple divisive nationalist claims to soil, displacement, and unrealized desires for a homeland that have largely shaped relations between Sindh’s natural (of the soil) and its unnatural (migrant and Urdu or other-speaking) inhabitants. It also addresses a wider preoccupation in Pakistani society: that is, the nervous apprehension of identity, the tentative force of the push for rights, paradoxes of national and theological idioms of finding peace or assimilating the experience of strangeness, alienation, fragmentation, and violence (Ansari, 2005; Gayer, 2014; Jalal, 1995; Shaikh, 2009; Verkaaik, 2004). The fractures that accompanied Karachi’s monstrous expansion and vexed annexation from Sindh are interwoven with complex traces of colonial and pre-colonial pasts, as were colonial rule and land dispossession textured into the very institutional form of the state (Jalal, 1995). They shaped differences between capital and ‘interior’, with capital denoting commerce and the time-clock of colonial rule and civility. The ‘interior’, like other unconquered colonial interiors, denoted a fecund place of mysticism, saints’ worship, fascination, and unending mystery. They also shaped sharp urban–rural and socioeconomic divides that fueled nationalist, ethnic, and separatist politics, with Karachi dominating as Pakistan’s industrial and commercial capital, and over 75% of Sindh’s rural population living below the poverty line (UNDP, 2015).

While Pakistan avowed its identity as a postcolonial Islamic state free of British imperialism, in appropriating the ideas and technologies of sovereignty and nationalism, it acted imperially (Anand, 2012). This produced the ‘sacralization’ of party politics, incomplete and unequal development regimes, the evolution of an ‘Islamic army’, military-foreign policy approaches justified through Islam, the suppression of non-Muslims, and a lack of a consensus on Islam articulated through perpetual ethnic, nationalist and religious differences that Shaikh (2009: 8) likens to a ‘cancer in the body politic’. Notwithstanding, much evidence exists of the local syncretic realities of people’s lives in Pakistan and across South Asia (Jones, 2014). Parallel forms of internal suppression occurring contiguously across post-partition South Asia similarly established ‘postcolonial informal empires while instilling constant anxiety about the precariousness of the imperial state project’ (Anand, 2012: 83).

This analysis does not focus on these alternations, divisions, and comminglings between the borders of Sindh and Karachi cartographically, or as statistical fact. It seeks to destabilize any pre-determined arrangements of places and parts and to open an interstitial terrain between classifications and borders between territories and communities. It also eschews re-reading the city through corrective postcolonial identity politics – with its emphasis on ethnicity, rights, exclusion, sectarianism, opposition to military oppression, and the spatialized urban geography of militant ‘no-go’ areas. Instead, I propose that looking for convergences between urban life and topography can offer fresh departures for examining relations of strangeness and familiarity that characterize Karachi – as it is moved by the waxing and waning, and ebb and swell, of growth and change. Topography refers not only to arrangement of the natural and artificial physical features of an area (OED), but also to an imaginary, real, urgent, and remembered patina of connections of people to the soil, land, and dwellings they live in. (Continues)

This analysis does not focus on these alternations, divisions, and comminglings between the borders of Sindh and Karachi cartographically, or as statistical fact. It seeks to destabilize any pre-determined arrangements of places and parts and to open an interstitial terrain between classifications and borders between territories and communities. It also eschews re-reading the city through corrective postcolonial identity politics – with its emphasis on ethnicity, rights, exclusion, sectarianism, opposition to military oppression, and the spatialized urban geography of militant ‘no-go’ areas. Instead, I propose that looking for convergences between urban life and topography can offer fresh departures for examining relations of strangeness and familiarity that characterize Karachi – as it is moved by the waxing and waning, and ebb and swell, of growth and change. Topography refers not only to arrangement of the natural and artificial physical features of an area (OED), but also to an imaginary, real, urgent, and remembered patina of connections of people to the soil, land, and dwellings they live in. (Continues)

___________________

About the Author

Nichola Khan is a Reader in Anthropology and Psychology, and Director of the Centre for Research in Spatial, Environmental and Cultural Politics at the University of Brighton. She is author of the following books: Mohajir Militancy in Pakistan (2010, Routledge), Cityscapes of Violence in Karachi (ed., 2017 Hurst & Co.,) Mental Disorder: Anthropological Insights (2017, University of Toronto Press) and Arc of the Journeyman: Afghan Migrants in England (in press, University of Minnesota Press). She is currently developing a literary anthropological project on war and migration in twentieth-century Chinese South-East Asia.