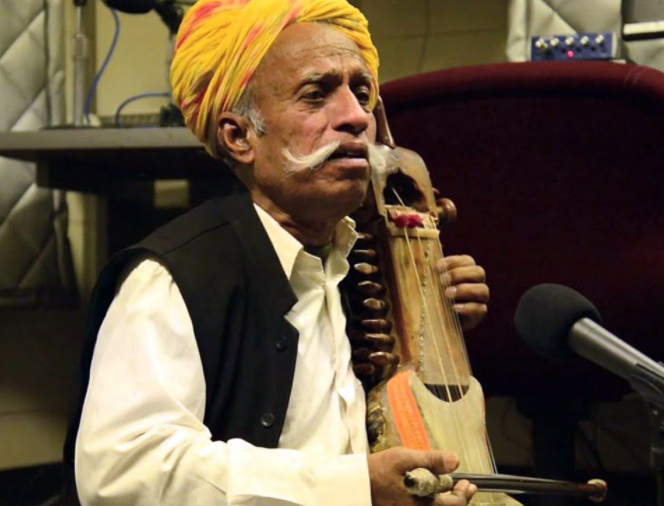

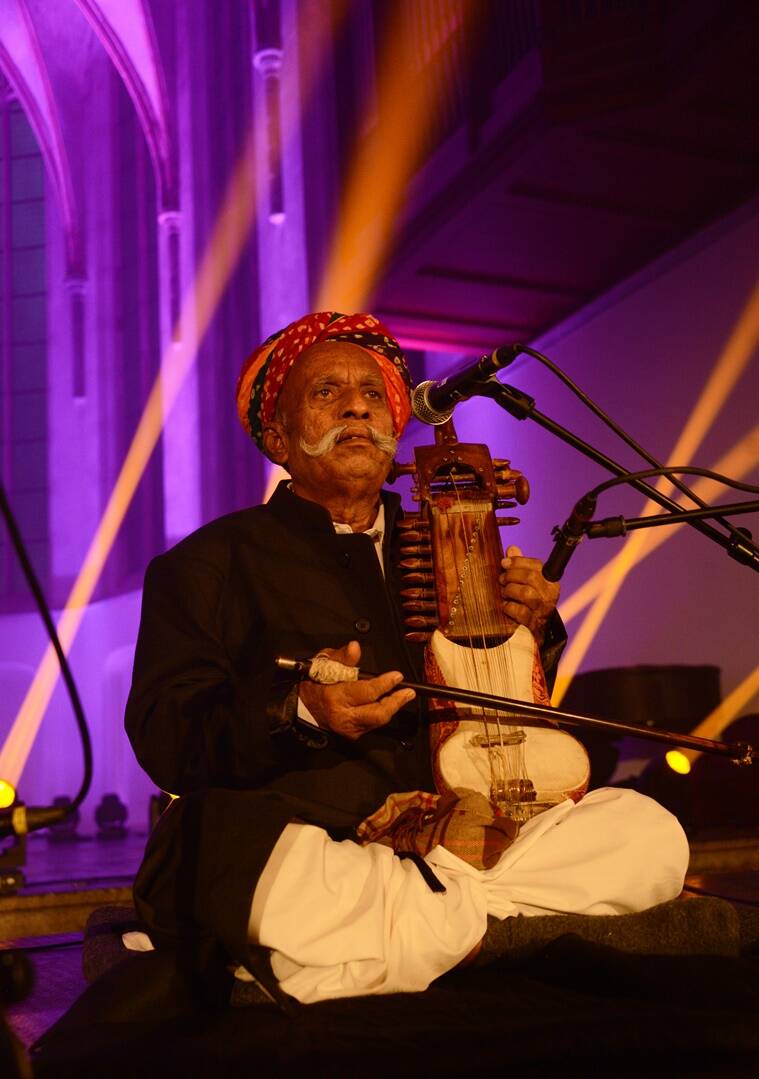

Hailing from Raneri village of Jodhpur, Lakha Khan says ‘Sindhi Sarangi’s sound imitates the human voice.

The Aga Khan Museum has produced a three-part documentary series called Searching for the Blues on the musicians, which tells one of the most remarkable stories of our time. One of the musicians is Lakha Khan, from Raneri village in Jodhpur.

Lakha Khan had been playing and singing for half a century at that time, making a living by performing at local events like weddings and births of the local feudal Rajput lords.

Khan was playing for the same families that his father and grandfather and great-grandfather played for. Even his instrument was one that came down to him from his ancestors and on which he still played.

This instrument was the Sindhi Sarangi, whose sound imitates the human voice.

Lakha Khan was the seventh generation of his family to be playing the instrument. He sang compositions including Hindu bhajans, Sufi kalaams, and folk songs in five languages: Seraiki, Sindhi, Marwari, Punjabi and Hindi. The quality of the music incorporates religious and spiritual themes in soulful, simple songs.

In 2021, Lakha Khan received the Padma Shri Award, coming into a prominence that was his by right.

Lakha Khan is only one of the many men and women from Rajasthan that the documentary series exposes. And it is astonishing for many who may have wide exposure to music, to see how such world-class performers are so little known in their own land.

Lakha Khan is only one of the many men and women from Rajasthan that the documentary series exposes. And it is astonishing for many who may have wide exposure to music, to see how such world-class performers are so little known in their own land.

The last episode of the documentary features Dane Khan, the son of Lakha Khan.

Till some time ago, Dane Khan was driving a truck because there it was not possible to make a living from the family tradition.

But happily, his father’s growing prestige and frequent touring gave Dane Khan the opportunity to provide for his family while continuing the tradition for an eighth generation.

Of course this is great news for our culture, which has found a carrier who will take it forward for another few decades, but it also reminds us of how much needs to be done.

When the hotel staff refused to serve Lakha Khan

A couple of years ago, at a famous boutique hotel in Jodhpur, a server refused to serve tea and refreshments to the Lakha Khan and his family members. The Rajasthan-based musician had been invited to the hotel for a recording session by Ashutosh Sharma, one of the founders of NCR-based record label Amarras Records. Sharma was aghast that a well-known hospitality group wouldn’t serve food to a legend from their own state.

Khan is one of the few players of Sindhi sarangi, a folk fiddle capable of “emulating the human voice”. He also sings alongside. “After much back and forth, they said they would put out his food in the parking lot because Khan is a Manganiyar while the waiters are from upper castes,” said Sharma, who then decided to pack and leave the hotel immediately. He also took away the travel business he was handing out to them annually through his travel agency.

Khan didn’t make much of the incident then. He still doesn’t. According to him, these things stopped weighing heavy on him a long time ago. “All this happens. It’s fine. I don’t feel so bad about it anymore,” said Khan over the phone from Raneri, a sleepy little village near Jodhpur.

Khan didn’t make much of the incident then. He still doesn’t. According to him, these things stopped weighing heavy on him a long time ago. “All this happens. It’s fine. I don’t feel so bad about it anymore,” said Khan over the phone from Raneri, a sleepy little village near Jodhpur.

About winning the Padma Shri Award, Lakh Khan said, “The award is a recognition for my music and I welcome it. It will draw attention to this state, to this art form, and to the patronage that it so desperately needs while going ahead.”

Khan in Hindi with a touch of Marwari, said, “As for the caste system, it is extremely ingrained in people. It probably will change with more education in the future. My grandchildren now go to school. It may change after all,” he adds.

For centuries now, the caste arrangement has been such that the Manganiars, considered a lower-caste Muslim community, has been attached to Rajasthan’s Rajput community for centuries. The musicians, for years, have performed at weddings, childbirth, and family festivity among others. A lot of the songs that the musicians sing are in praise of the Hindu deities and in celebration of Holi and Diwali. But the system of treating them differently and caste discrimination has persisted for years. The death of a Manganiar in Dantal village near Jaisalmer in 2017, one who was allegedly beaten to death in a temple, rocked the community. As many as 200 from the community fled the village and camped 20 km away from the village under police protection. “They have now become Hindus,” says Khan’s son Pappu referring to the pressures from a few organizations.

“It’s unbelievable when a Rajput translator, who is going to earn a living translating Lakha ji, refuses to have water from his house. Like in an auto mode, Lakha ji tells someone to fetch mineral water from outside. To this man, Lakha ji’s brilliance as an artist does not trump Caste.

“It’s unbelievable when a Rajput translator, who is going to earn a living translating Lakha ji, refuses to have water from his house. Like in an auto mode, Lakha ji tells someone to fetch mineral water from outside. To this man, Lakha ji’s brilliance as an artist does not trump Caste.

Born into a family of musicians from the Manganiyar community, Khan was trained at an early age by his father, also a Sindhi sarangi player. The instrument which is often associated with the Langas, another musician community from the state, has been in Khan’s family for generations, starting from his great-grandfather. As of now, only a handful of Sindhi sarangi players remain, among whom the name of Lakha Khan stands tall. “It is a tough instrument to learn and master, which is why the younger generation among us plays the baaja (harmonium) more. I fell in love with the sound when I would hear my father in riyaaz. I started learning when I was about 10,” says Khan, who still sits outside his small home in Raneri and practices. He recalls spending four anas to listen to a Manna Dey or a Mohammad Rafi song through a bioscope – the portable projector. He would then go back and try to play them on his sarangi.

His first performance was in the late ‘70s, under the guidance of musician and ethnomusicologist Komal Kothari, who helped Rajasthani folk music travel out of the state. In 1986, Khan performed in France, his first-ever concert outside India. He toured the UK, Russia and Japan later. But then he fell through the cracks, and was not doing much until Sharma and Amarras’ other founder, Ankur Malhotra, rediscovered him and recorded his music, a lot of it in and outside Khan’s home.

The duo was taken in by Khan’s vast knowledge and the ease with which he could juggle Ram bhajans, Sufi qalams and folktales tied with melody. Khan sings in several languages including Marwari, Sindhi, Hindi, Punjabi and Multani. Often his concerts are replete with odes to Guru Nanak, Lal Qalandar and Lord Ram and Krishna. Also, what’s extremely interesting about Khan is the combination of his sarangi and his throaty yet soft and modulated voice. “We don’t modulate our voices like classical musicians do. That is generally for a certain kind of audience. In folk, we sing to reach the audience in large numbers. Which is why our music is simple and works for everyone around the world even though so many people don’t understand the words we sing,” says Khan.

The duo was taken in by Khan’s vast knowledge and the ease with which he could juggle Ram bhajans, Sufi qalams and folktales tied with melody. Khan sings in several languages including Marwari, Sindhi, Hindi, Punjabi and Multani. Often his concerts are replete with odes to Guru Nanak, Lal Qalandar and Lord Ram and Krishna. Also, what’s extremely interesting about Khan is the combination of his sarangi and his throaty yet soft and modulated voice. “We don’t modulate our voices like classical musicians do. That is generally for a certain kind of audience. In folk, we sing to reach the audience in large numbers. Which is why our music is simple and works for everyone around the world even though so many people don’t understand the words we sing,” says Khan.

He resumed international touring in 2013 and toured the US three times with sold-out shows, apart from performing at the famed WOMEX artiste showcase in Finland in 2019. During his concerts, he is usually accompanied by his son Dane Khan, who plays the dholak alongside. Both his sons Dane and Pappu had stopped learning in the middle and gone towards other labor-intensive tasks because they thought this wouldn’t help them earn enough. In the last few years, they have returned to music. Pappu is back to learning Sindhi sarangi. “I hope more people turn up to learn this. Otherwise, there will soon be no one to play the instrument after some years,” he says.

Current generation is very distracted

Speaking of a bygone era when his father Tharu Khan urged him to continue his legacy, Lakha Khan says, “Like an obedient son and a faithful pupil, I strictly adhered to his teachings on how to hold tones and internalize the stories behind ragas”. Through unflinching dedication and discipline, Khan eventually mastered the art of keeping the flow of the bow in harmony with the notes.

Today, the preservation of the community’s musical heritage is plagued with deep-set fears that it may not last even few years down the line. “The sarangi and kamaicha are complex instruments to play because of which most Manganiyars are picking up an easy alternative like the harmonium,” laments Khan.

“Nowadays, people prefer DJ’s and electronic music. Mine is not electronic music. Every genre has different tunes and people have their own preference for styles of music. For instance, sargam, bhajan and Sufi music have different emotions and feelings attached to it. Although I like contemporary music, the raag doesn’t touch my heart. I think the youngsters prefer more of the up-tempo music, and that is their preference,” he says.

“The quality is going down…. it is not the same quality as before – both in terms of the quality of the performers and their repertoire. The great masters have passed away and the next generation do not know as many songs,” Lakha Khan viewed about the folk music in Rajasthan.

_______________

Source: The North Lines and Indian Express